1970 – Pan American Airways

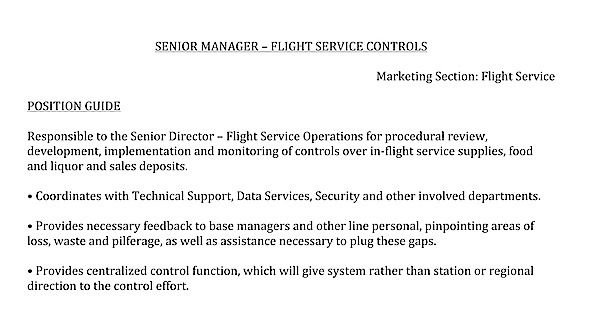

On November 30, 1970, I left 605 Third Avenue and moved to 535 Fifth Avenue, becoming Senior Manager – Flight Service Controls with Pan American World Airways and reporting to Frank Lennon, whose new title was Senior Director – Flight Service Operations. [Pan Am used ‘Flight Service’ rather than TWA’s ‘In-Flight Service’ reference.] Frank reported to Vice-President Larry Burtchaell.

On November 30, 1970, I left 605 Third Avenue and moved to 535 Fifth Avenue, becoming Senior Manager – Flight Service Controls with Pan American World Airways and reporting to Frank Lennon, whose new title was Senior Director – Flight Service Operations. [Pan Am used ‘Flight Service’ rather than TWA’s ‘In-Flight Service’ reference.] Frank reported to Vice-President Larry Burtchaell.

With my position came a monthly salary of $1334, which equaled an annual income of $16,000; I don’t remember if that was a figure that I negotiated but it amounted to about 10% more than my TWA compensation. In addition, I received a term pass, although more restricted from the one I left across town. It permitted positive-space economy flights on business with upgrade to first class on a standby basis, subject to capacity limitations, although we were expected to ride one-way in the back of the airplane in any event. Unlimited personal, space-available flying in economy was also included.

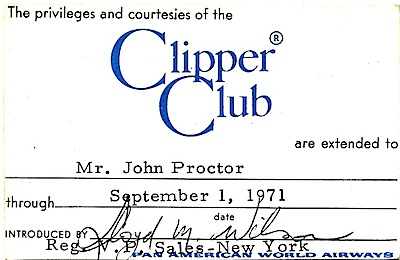

The ability to fly domestically was restricted to a few “co-terminal” routes, over which Pan Am operated but could not carry local traffic; New York–Miami and Los Angeles–San Francisco were two examples. Otherwise, limited interline passes or reduced-rate ticket purchases were available. But a nice new perk was admittance to Pan Am’s Clipper Club lounges.

The Flight Service organizational setup differed from TWA in several respects. For example, the stewardess/purser domiciles [‘bases” at Pan Am] reported to Frank, rather than to the station mangers as with TWA. Crew scheduling, recruiting and training reported to Wally Russell, Director – Flight Service Administration, while overall responsibility for food and beverage fell to Jay Treadwell, Director – Food Service (I think that was his title). We had some really interesting people within our group. Among them was Neil Reyer, who worked in catering planning and later ran the Copter Club atop the Pan Am Building. Hugo Ralli was in charge of menu planning, a formidable task. Lyle West was my immediate boss when I first arrived, best pals with John Hale. Among the base mangers I remember are Joe Vissicchio (New York), Eddie McIntyre (Washington DC) and John Tendick (Seattle).

The Flight Service organizational setup differed from TWA in several respects. For example, the stewardess/purser domiciles [‘bases” at Pan Am] reported to Frank, rather than to the station mangers as with TWA. Crew scheduling, recruiting and training reported to Wally Russell, Director – Flight Service Administration, while overall responsibility for food and beverage fell to Jay Treadwell, Director – Food Service (I think that was his title). We had some really interesting people within our group. Among them was Neil Reyer, who worked in catering planning and later ran the Copter Club atop the Pan Am Building. Hugo Ralli was in charge of menu planning, a formidable task. Lyle West was my immediate boss when I first arrived, best pals with John Hale. Among the base mangers I remember are Joe Vissicchio (New York), Eddie McIntyre (Washington DC) and John Tendick (Seattle).

The Flight Service department was billeted on Fifth Avenue because all the office space in the Pan Am Building was occupied by the airline or leased out. I believe we were on the 4th or 5th floor of this much older building, a far cry from the sweeping views on the 38th floor back at 605. But I got my exercise in by walking to work from my apartment, heading across town to 5th Avenue, then south to the office. A pleasant alternate route was down Park Avenue, which I often took.

My initial duties were directed towards the control of in-flight liquor and movie headset revenue. I had two analysts reporting to me, Gretchen Forbes and Bill Hesse. Gretchen came to the position from the stewardess corps and Bill from station operations.

Our first major task was an overall upgrade of the way liquor and headsets were inventoried and how the money was accounted for and deposited. Up to this point, pursers carried the funds for their entire trips and turned the money in upon return to domicile, which could stretch out as long as a week. A week’s worth of revenue often amounted to a fairly large sum of money and knowledge of this could make the pursers susceptible to being robbed.

Our first major task was an overall upgrade of the way liquor and headsets were inventoried and how the money was accounted for and deposited. Up to this point, pursers carried the funds for their entire trips and turned the money in upon return to domicile, which could stretch out as long as a week. A week’s worth of revenue often amounted to a fairly large sum of money and knowledge of this could make the pursers susceptible to being robbed.

One of the things I quickly learned at Pan Am was that dealing with labor unions was more complicated than at TWA. For one thing, there were more of them and as a result, more organized employees. Unlike TWA at the time, airport passenger service workers were in a union, and even secretaries were organized. Frank was fortunate to have one of the “exempt” positions assigned to his secretary. But making policy changes was much more difficult with so many contracts to deal with. I was told that it took employees from three different unions just to get an aircraft parked and the boarding door opened on arrival.

My first suggestion to Frank, which he approved, was to have pursers begin depositing money at each overnight stopover rather than hauling large sums around for an entire trip. It made a lot of sense, but faced serious uphill battles. First, the pursers were not happy with the idea at all. I’m not here to insinuate that they were all ripping the company off, but with all the different currencies involved, there were numerous opportunities for fund manipulation.

One of the nicest memories I still savor when thinking of my time at Pan Am; here’s her picture. Jaenee was the love of my life for more than a year; how did I let her get away?!

An additional challenge was that money deposited at some offshore locations could not be taken back out of the country due to local laws. While these funds could be used for local purchases, it presented accounting challenges.

Another plan, which I believe we successfully implemented, was to limit the number of acceptable currencies. Until then, Pan Am took almost any form of payment. This, of course, was long before airlines began allowing in-flight payment by credit card.

A further proposal that didn’t fly was to sell coupons on the ground, good for in-flight purchase of liquor and rental of TITA – Theater in the Air – movie headsets, taking cash completely out of the equation. By allowing them to purchase these “chits” with their tickets, business travelers could charge these items to their company credit cards. It would also be easier for leisure travelers to pre-pay.

This proposal hit a brick wall with too many people who gave reasons as to why it would be impossible, rather than coming up way ways to make it work. In retrospect, it wound up taking nearly 40 years for the airlines to adopt “cash-free” cabins aloft.

Unlike the computerized revenue accounting in place at TWA, Pan Am will still using manual procedures and forms. Updating this alone was a major project, which took up much of our time and, again, I won’t accuse anyone of less than honest dealings, but the newly marked inventory forms resulted in a sudden revenue spike from in-flight sales.

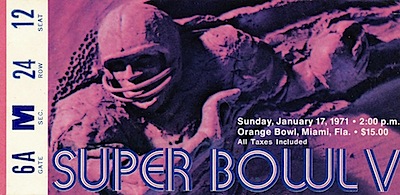

I did manage to get in some interesting travel in on company business, including a few visits to Miami, where Pan Am maintained a crew base. One of these “official” business trips just happened to coincide with Super Bowl V, which Frank and I attended. There was also a base manager’s meeting held in Honolulu, a pleasant diversion from harsh New York winter weather.

At the end of April 1971, I undertook a little trip to audit our liquor controls and evaluate the new procedures we had implemented. Departing from JFK, I rode the first leg of Flight 801, Pan Am’s daily 707 New York–Tokyo flight, which made a fuel stop at Fairbanks. From there, I switched hats, so to speak, and jumped on board one of Alaska Airlines “Golden Nugget” jets down to Anchorage, connecting with its “Golden Samovar Service” to Seattle. Pan Am, at least technically, competed with Alaska in this market, hence the opportunity to sample another carrier.

Click to read my flight report on Alaska.

From Seattle, it was over the pole to London on Pan Am Flight 122, a 707. In my logbook, I noted three of the cabin crew: Mary Ellen Runge, Elaine French and Kathy McDonough. I believe Mary Ellen was the purser, very senior. The flight left Seattle at mid-day and even in early spring; it was never totally dark, all the way to London, where we circled for nearly a half-hour, awaiting lifting of the curfew at Heathrow Airport. I returned to JFK on 747 Flight 101 May 2nd.

Flight 801, shortly after I disembarked at Fairbanks. Looks like there was an issue with No. 2 engine. ©Jon Proctor

Yearning for the Twin Globes

Learning the ins and outs of the legendary Pan Am was an exciting time for me. I was given a tour of the Pan Am Building and remember sitting ever so briefly in Charles Lindbergh’s chair in the boardroom. I was taken to lunch at the rooftop Copter Club and allowed to walk around the helicopter pad, which had been closed by then. Being a student of civil aviation history, I took advantage of every opportunity to learn more about “The World’s Most Experienced Airline.” Historian Althea Lister, a 40-year company veteran when I met her, made much of its history available in various forms.

Working for Frank Lennon was the most rewarding experience of all. He was a great mentor, stretched my abilities at every turn, and provided 110% support.

I guess my heart never left TWA though, and I couldn’t get that TWA 747 supervisor job out of my head. By then, the title had been changed to Director – Customer Service (DCS), and hiring for the position was still in full swing.

Then Dick Veres called to ask if I would like to come back to TWA as a DCS. When I said yes (it may have been “HELL yes!”), he offered, “Get your weight down and there’s a spot for you.” It was the greatest incentive for a diet, which I started in earnest the next day, dropping those excess pounds in two months. And the rest, as they say, is history.

On June 24, I submitted my letter of resignation to Frank, to become effective July 9, 1971.