1974 – Back to New York

With my car still in the TWA employee parking lot at O’Hare, I flew to La Guardia Airport on March 31, 1974 and officially began my new job on April Fools Day; was there a message here? No, not really. In retrospect, I had made the right decision in more ways than one.

With my car still in the TWA employee parking lot at O’Hare, I flew to La Guardia Airport on March 31, 1974 and officially began my new job on April Fools Day; was there a message here? No, not really. In retrospect, I had made the right decision in more ways than one.

On that day I returned to an office in Manhattan with interesting challenges. My new manager, Mike Mudge, escorted me into the office of his boss, Tom McClain, Staff Vice President of Passenger Service Programs. A direct and to-the-point administrator, Tom reviewed my job description briefly and asked if I had any questions. He then informed me that I would be held accountable for these responsibilities, adding, “If you need any help, let me know.”

We shook hands and headed back to Mike’s office for a more informal review.

The Job Challenge

With my job came two supervisor positions. Larry Thierman, a seasoned veteran who cut his teeth in the corporate offices, had already filled one. I began interviewing for the open job immediately and hired John McGlade, a DCS who had ramp and maintenance experience. Two better workers you couldn’t find, both with varied backgrounds and a good deal of enthusiasm.

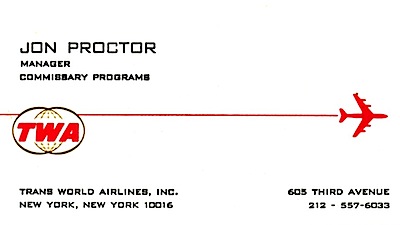

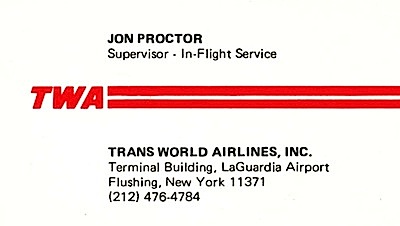

My new job entailed administrative responsibility for the Commissary function, which included transporting, loading and unloading food and beverage supplies on TWA aircraft. The department prepared and packed support items such as first-aid kits, liquor, soft drinks, cocktail napkins, stirrods and PSK (passenger service kit) ingredients such as aspirin, coat tags and alike. At smaller stations, our people completed tail washes on 727s and DC-9s, which got dirty thanks to throwback from engine-thrust reversers.

Commissary Programs had the administrative responsibility for loading food and beverage items aboard our fights. Here three high-lift Commissary trucks simultaneously service at 747 at JFK. ©Jon Proctor

“Administrative responsibility” amounted to supporting the airport people who carried out these functions, writing and updating procedures and our portion of the Dining & Commissary manual. We coordinated closely with the Dining Programs department, where menus were conceived, and In-Flight Service, which was responsible for serving procedures.

I worked with some wonderful and dynamic people in the office, including some who were there during my 1969-1970 tour. Among them were Dieter Buehler, Mike Duarte and Burt Kenyon in Cabin Service Programs.

Finding a Place to Live

My hectic schedule made it difficult to find permanent housing in the New York area. After a month of living in a hotel, I really needed to put down some roots. Having purchased a condominium in Chicago a year earlier and selling it at a modest profit, I preferred to buy again. Co-ops in Manhattan were out of my price range, and even rentals were scarce and pricey. I nearly bought a house on Long Island, then finally found a condo in the charming town of Bethel, Connecticut, between Danbury to the west and Newtown to the east.

Riding the Train

The Danbury branch of the New Haven Railroad (part of Metro-North) operated two weekday, through trains to Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan, a short walk from my new office. It was going to be a long commute, leaving Bethel at 6:19 a.m. and returning at 7:16 p.m. During the winter months, I never saw the light of day at home during the week. Fortunately there was some travel associated with the job, which broke up the routine.

As much as I disliked the long days, the train ride was tolerable, even relaxing. Between snoozes and business-related paperwork, the southbound trip went fairly quickly. Bethel was just the second stop on the route, so there were plenty of seats to choose from on these diesel-powered trains, made up of older, hand-me-down coaches. After four stops en route to Norwalk, the “early” train proceeded direct to GCT. If I missed it, there was a second through train but it was a milk run between Norwalk and the City.

Despite their age the trains were almost always on time; the few long delays I recall involved wet leaves on the tracks in the fall, and one time when we had a “dog” locomotive that couldn’t get us up the incline between South Norwalk at Bethel. I got off at Cannondale with another Bethel commuter who called his wife; she came down and picked us up.

I joined a friendly poker game on the return ride, pretty much nickel-dime. As a newcomer, I had to sit on my briefcase in the aisle until space opened up in a regular seat. Some of the players had been riding that train for more than 20 years. One, “Crazy Eddie,” as we called him, claimed to have buried five players from that game! For the privilege of participation, the conductor collected 25 cents per person. In return, the seats were informally blocked for us and a game board was provided, along with a deck of cards. Traditionally, we only drank on Fridays, although once in awhile someone would break the rule and buy a round, but that involved a trip to the smoke-filled, crowded bar car.

I actually got into the game thanks to Pan Am pals Lyle West and John Hale, who I had worked with during my short stint at the Big Blue Ball. Also in that game was Dick Ensign, Senior VP with Pan Am, who started his career at Western and was credited with originating the airline’s Champagne and Hunt Breakfast Flights. Dick was a great guy and we kept in touch long after I left 605 and he returned to Western; I still have some of his letters. Dick just passed away within the past few years.

Standby in Rome

I was barely into my new routine when trouble began brewing at our European flight attendant domiciles. With different work rules, the Rome-based cabin crews could strike up to four hours at a time and suffer no consequences. Some began sitting down on flights and refusing to serve the passengers. To combat the situation, F/A-qualified management people were sent across the pond and placed on standby. As a recent DCS, all my qualifications were still in good standing and on May 11, and I was sent to Rome, hooking up with both DCS types and other managers.

On the ground at Athens during the European shadow mission, two European cabin crew members are on the left; that’s me in the center, with Jan Golon and Dennis Mangus. ©Jon Proctor

After four days of playing tourist there, things quieted down and I was told to come home, which was fortuitous as I had a meeting in San Francisco a day later. I flew back to JFK and made a 3-hour connection out to the West Coast. Another meeting in Kansas City followed a day later, plus an overnight stop at Chicago to finish packing up and get my furniture headed east; I was gone nearly two weeks.

Five months later I was sent back to Europe after it was announced that the Rome and Paris domiciles would be closed in 60 days. To combat expected sit-downs and sick calls, five flight attendant-qualified management employees were assigned to “shadow” every intra-European 707 flight. Along with Joe Ballweg, Jan Golon, Dennis Mangus and Kathy Powers, I bounced around between Frankfurt, Paris, Rome, Athens and Tel Aviv for two weeks. Although there were some problems on other flights, all the crews we flew with did their jobs and the five of us were basically relegated to passenger status. We had a few nice layovers, including some long enough to do a little sightseeing. But after two weeks of flying every day, I was happy to wind up at Rome, then return to New York.

Aircraft Cleaning

A big part of my administrative responsibilities was aircraft interior cleaning. Not long before I came to the job, the higher-ups at TWA decided to combine the Ramp Service function with that of Fleet Service, those folks who actually cleaned the cabin interiors. The idea was to save manpower by cross-utilizing personnel.

In November 1974 the first TWA airplane appeared in a new livery. 747-131 N53111 is seen at Chicago-O’Hare. ©Jon Proctor

Frankly, it started as a marriage from Hell. Fleet Service workers were mainly women, and for the most part older and more senior than the Commissary Ramp Service men (no women yet). With their jobs combined, the women immediately migrated to indoor jobs in Commissary, assembling liquor kits and building up other supplies. In turn, the former Commissary fellows were often relegated to cleaning aircraft cabins, and they were not happy about it.

One of my first challenges was to enlist the help of some of the maintenance foremen who formerly supervised the Fleet Service workforce. A few cleaning functions remained with them, at locations where we did major aircraft maintenance. After assuring these people of my desire to improve our relationship, they were very helpful. And I needed their help.

Even as the learning curve between workforces improved, it was obvious that the aircraft cabin appearance was not up to par. Part of the problem was an ill-conceived marketing-sponsored program that began in fall 1970 with a remake of the 707 cabin interiors, part of the introduction of “Ambassador Service,” aimed at keeping these older aircraft looking as desirable as the newly introduced 747s. At the time, it was the largest capital expenditure ever undertaken for refurbishing aircraft interiors.

New fabrics were selected with 12 possible “bright, vibrant” color combinations in coach and four in first class. These patterns varied by individual aircraft, presenting a nightmare for those charged with tasks as simple as changing a soiled seat cushion. Imagine looking up a fabric part number in a phonebook-sized catalog, then actually pulling it from a storage room. In addition, the first-class pairs contained eight separate pieces of fabric.

By the time I returned to staff, the program had been extended to most of the narrowbody fleet, and it became a challenge just to keep the interiors looking presentable. The light fabrics got dirty quickly and the carpets were an even greater problem.

A plan was devised to conduct deep interior cleaning each 300 hours of flight time. The biggest task was changing out fabrics and carpets on these overnight layover projects, undertaken at Boston, New York, Chicago, Kansas City, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Along with Fleet Service Foreman Bill Floberg from the Kansas City Overhaul Base, I traveled to locales where the “phase checks” were taking place, conducting surprise visits early in the morning. Compliance was only so-so, and it took some time to get people familiar with the task and coordinate the work.

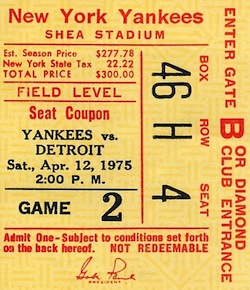

A weekend Yankees game I attended, played at Shea Stadium while the House that Ruth built was undergoing major renovations. ©Jon Proctor

At that point we began pressuring for a simplification of the interior fabric design. It took a good deal of cajoling but finally common sense and the prospect of saving money resulted in a reduction to nine fabric colors and a dark blue carpeting fleet-wide. After requesting a mockup of a first-class seat pair with blue vinyl replacing four fabric sections, I flew to Kansas City to see the proposed changes. It was approved on the spot by upper management. What I remember most was the fabric shop foreman who showed us the mockup. She obviously had plenty of experience in that department and explained the various facets of the seat configuration changes. I glanced at her TWA ID badge and noticed that her company seniority date was prior to when I was born. Experienced indeed.

Much of my work involved interfacing with TWA’s Corporate Industrial Engineering (CIE) department, which as domiciled at the Kansas City Overhaul Base. B.R. “Bobby Ray” Patterson was my CIE counterpart and was responsible for determining manpower requirements for ramp personnel. This was always a challenge because it directly affected our staffing. I won’t go into all the details, but CIE measured right down to the “man minutes” for every task, be it assembling liquor kits, loading and unloading galleys or running a vacuum cleaner up and down the aircraft aisles.

When upper management required station personnel to work 10% under budget, it meant only 90% of the manpower allocated by CIE would be on the payroll. This was usually done by not filling vacant positions. The problem: CIE didn’t throw around extra man minutes and without full staffing, some of the work didn’t get done.

Assembling liquor kits, cleaning audio headsets and aircraft cleaning were among the items considered “deferred work,” i.e. tasks to be accomplished when time permitted. Obviously, unloading galley equipment, freight and passenger luggage had to get done; so Commissary-related items fell by the wayside.

Thrill of a lifetime: meeting legendary World War II hero Jimmy Doolittle, who led the famous Tokyo bombing run the day I was born: April 18,1942. I met him at a Wings Club banquet in October 1975. ©Jon Proctor

Moving On

In January 1976, I put together a detailed presentation to upper management, showing how the 10% staffing level reduction made it impossible to properly complete Commissary responsibilities, thus hurting our product. The CIE folks were strong supporters of my claim, saying that if the work could be done with 90% of their calculated staffing level, there was something wrong with their calculations!

I saw a lot of nodding heads during the meeting as I went through the flip chart, quoting numbers and demonstrating my pitch for full staffing. When I asked for comments at the conclusion of the presentation, many of those attending who had earlier complained that this workforce reduction was unrealistic, unfair and hurting the operation, instead pledged to the senior vice president conducting the meeting that they would double down, work harder and somehow get the job done. I scratched my head, wondering why I had bothered with the whole issue in the first place. It was time to move on.

At about the same time, Mike Mudge left to assume his long-sought position as station manager at JFK. More than a year earlier, Tom McClain had become Vice President of In-Flight Service and was replaced by Ray Roda. Mike’s departure presented a good opportunity for me to leave and let his successor select his own choice for my position.

I phoned my old boss, Dick Veres and asked if he had room for another DCS at the JFK domicile. Dick said he would welcome me back and I left regular duty at the corporate offices for the last time.

Now, instead of riding the train five days a week, I would be driving to JFK five or six days a month. The two years I pledged to this job had nearly expired and I left with no regrets, considering the whole experience a character builder. We had made good progress in many areas, which made it all worthwhile.

Back in the Air, Briefly

One of my first trips back was to Las Vegas, where I caught this shot of L-1011 N31019. ©Jon Proctor

I took a week’s vacation and returned to the DCS job on February 1. By then, the title had been changed to IFSS – In-Flight Service Supervisor, but the job description remained the same. I was given one-month assignment on domestic routes before returning to trans-Atlantic flying.

My initial overseas trip was a bit of a challenge, with a long first day (and night, and day), operating New York–Madrid–Malaga–Madrid. Instead of laying over at Madrid with the rest of the crew after the first stop, I flew down to Malaga and back. The lowly DCS did three legs straight away, allowing him/her to complete the pairing in three days instead of four. There was only a beverage service on the short segments within Spain, and TWA was not allowed to carry local passengers between the two cities, so it was an easy day for the cabin crew and a challenge for the IFSS just to stay awake. More torture came in the form of landing at beautiful Malaga, on the Costa del Sol, and not being able to get off for a layover.

I asked for more domestic trips; by summertime I was back flying within the U.S. and congratulated myself on having returned to the job I planned to enjoy until retirement, or so I thought.

Grounded

The company and flight attendant workforce had been in protracted contract negotiations for some time when things began to boil over as the 30-day countdown to a strike was about to expire at midnight June 4. An agreement was reached at the last minute while I was on a San Francisco layover and I felt relieved heading for the airport the next morning. Checking in at operations, I was told to call the New York In-Flight office immediately. The news was good and bad; we had a new contract but at a price. The IFSS program was to be discontinued. Along with my fellow IFSS brothers and sisters, I would still have a job, albeit as a ground supervisor of flight attendants. So much for driving back and forth to JFK five or six days a month.

The company and flight attendant workforce had been in protracted contract negotiations for some time when things began to boil over as the 30-day countdown to a strike was about to expire at midnight June 4. An agreement was reached at the last minute while I was on a San Francisco layover and I felt relieved heading for the airport the next morning. Checking in at operations, I was told to call the New York In-Flight office immediately. The news was good and bad; we had a new contract but at a price. The IFSS program was to be discontinued. Along with my fellow IFSS brothers and sisters, I would still have a job, albeit as a ground supervisor of flight attendants. So much for driving back and forth to JFK five or six days a month.

During a brief IAM strike in September 1976, I was assigned to Washington Dulles for a few days. While there I posed with this British Airways Concorde, which had only begun service to the U.S. a few months earlier. Little did I know that I’d get a ride on the same airplane, G-BOAA, less than a year later. ©Jon Proctor

The program was gradually phased out and my last trip returned to New York on September 3. Now simply a supervisor of In-Flight Service, I was assigned 40 flight attendants to look after. This entailed check rides to occasionally break the driving commute but most of the work was in the office. The base salary was unchanged, but we no longer had very much in the way of travel expense money and business suits replaced company-provided uniforms, further adding to costs. Office space was at a premium because there were so many of us moving into the ground positions. I was fortunate to move over from JFK to La Guardia Airport, with its slightly shorter commute and a cubicle I only had to share with one other supervisor.

Nevertheless it was a long winter, fighting traffic and weather. Combined with the 60-mile commute each way, workdays stretched close to 12 hours. Just about the time I was ready to pull my remaining hair out, an opportunity arose. The TWA flight schedule was to begin expanding by spring 1977 and several hundred flight attendants would be hired. An offer was made to any of us willing to downgrade to the F/A position and go on line ahead of the first new-hire class.

I was among seven former IFSS types who took the option and went through abbreviated training the first week in April. Already service- and safety-trained, we only needed to learn how to bid our schedules and complete some other formalities. I became a line flight attendant on April 4, starting over with job seniority. Company longevity counted only towards vacation and passes. The first year’s salary was meager and it would be a struggle to survive financially. I was facing the possibility of refinancing my condo in order to get by, and perhaps even borrowing some money. My savings would not last a full year.

But this lucky man was about to fall into an opportunity that would bridge the gap.

Jon, I so love reading your life story chapter by chapter. This one is when Jay and i moved to Bethel with our first baby and you and I reconnected. I look forward to every word to come.

Hugs, Jean

Jon, thanks for all the memories. The 300 hour cleaning crew was a lot of work but fun. I was the Supervisor; Dennis Dempsey assisted on my days off. We had 18 guys doing the deep cleaning on one 747; usually a 727 + cargo bins/hold. We had 2 carpet guys, 5 fabric changers. Aircraft type call out came from NYC planning at approx. 11 a.m. and the kit was pulled by stores. If they had problems they would call me in the middle of my day time sleep & ask if we could do perhaps 3 aircraft less the 747 due to fabric shortages.

Had great RSP Leads & very dedicated crews, thx to Lead RSP Mansour, Charlie Hawkins. I still have the brown fabric book in my collection and a small piece of the blue carpet with the gold stripe for 747 F/C and upper deck.

Dale,

I have been corresponding with Jon off and on for a few years now, usually on matters related to the Convair 880 and the L1011, which we both love. As Jon will tell you, one of my major interests is interiors and I am the proud owner of first class and coach seats from various TWA 880s and a swivel seat from the 747. They are still covered in the colorful seat covers that Jon describes in this chapter of his site. I also have carpet segments in blue and in red. The original blue one (which the guy is holding in the pic on this web page) was actually quite attractive. There were also a turquoise, orange and gold, and judging from some of the Convair 880s I saw prior to their breakup, they got really dirty.

You probably remember that the seat covers were each assigned numbers. Amongst the first 16 of them, 1-5 were blue/green, 6-9 were yellow-gold/orange, 10-13 were red and 14-16 an assortment. They came in various patterns: flowers (hey, this was the 70s), geometric and swirly. These first 16 were applied early on to the 707-131s and the 880s and 747s, in late 1970 early 1971. There were master sheets showing the seat cover combinations and carpet color for each individual aircraft, as well as a ‘Great Cities’ designator for each cabin design. I almost forgot, but originally there were seven different bulkhead covers which were mixed and matched to the carpets and seat covers. When the L1011s came along in 1972, the 727s and 707-331s were also being upgraded, and it seems that TWA marketing decided to add additional seat cover designs (as if you did not have enough already), and I bet you ended up with between 20 and 25 different ones by 1973, at the height of this program. There is one of them – a maroon splashy one – that looked great and showed up in N774TW, a 707 I rode ORY-IAD in July 1973. I have always wondered what number it was.

By 1975, some of the aircraft got some strange seat cover mixes as TW began to transition to a reduced set of seat covers. On jetphotos.net, Jon has posted some cabin pics of N11004 (an L1011) taken in summer of 1975 that shows an amazing jumble of colors in the economy cabin. I certainly applaud you and your colleagues for keeping these clean without losing your sanity!

Jon – As always, thanks for your detailed anecdotes about a fascinating time in your life, and in aviation. In the event that other interior and marketing fanatics are dropping by this page, I should add that this whole cabin refurbishment program was conceived and designed by Charles Butler Associates in conjunction with TWA. Butler and Associates were based in the New York area and actually did quite a bit of significant design work for commercial aviation throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The Continental 747 cabins, with each section taking on a colorful geographical theme (similar to TWA), were designed by Charles Butler. There were others, such as the Capital Viscount and the Trans-Canada Viscount and Vanguard. The basic cabin architecture of the Trident, VC-10, 111 and Vanguard v952 (North American market) were done by Charles Butler as well. Charles Butler passed away in late 1973, more or less putting an end to this design firm.

Hi and a good and healthy New Year

I am delighted about your stories of your aviation live. It gives me back many memories of this time. I myself worked with Lufthansa 43 years MUC FRA and abroad. I haven`t gone through all your stories yet but I will. The B707 was my favorite airplane, followed by the CV990. TWA was a great airline. A shame the US Government could`nt do more to keep it (also PAA) I ll keep checking your Website. Can you still use staff tickets ??? Maybe your coming to Europe someday.

Thanks for your kind words! I’m long retired now and don’t travel overseas but had many great experiences across the Pond! Regards,

Jon