1971 – TWA DCS

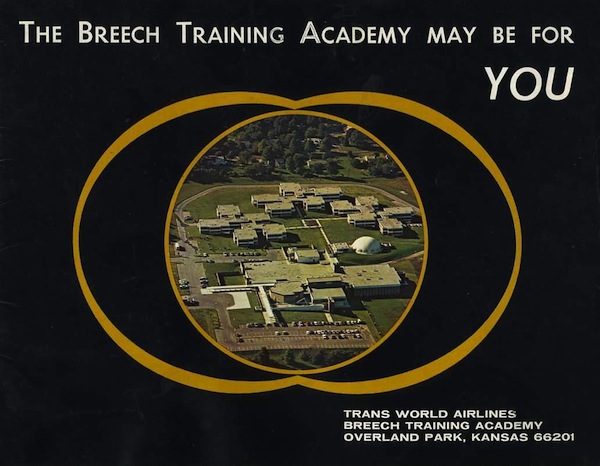

Monday, July 19, 1971 became my second TWA seniority date. On that day, I began six weeks of training to become a Director of Customer Service, or DCS, at the Breech Training Academy in Overland Park, Kansas, a suburb of Kansas City. This facility, named after TWA Board Chairman Ernest Breech, was built in 1969 and served mainly as the training center for hostesses and pursers. The campus-like setting contained various cabin mockups, classrooms, an auditorium, cafeteria and student lodging. By the time I got there, TWA had begun hiring male flight attendants, which brought an end to the Hostess title.

Monday, July 19, 1971 became my second TWA seniority date. On that day, I began six weeks of training to become a Director of Customer Service, or DCS, at the Breech Training Academy in Overland Park, Kansas, a suburb of Kansas City. This facility, named after TWA Board Chairman Ernest Breech, was built in 1969 and served mainly as the training center for hostesses and pursers. The campus-like setting contained various cabin mockups, classrooms, an auditorium, cafeteria and student lodging. By the time I got there, TWA had begun hiring male flight attendants, which brought an end to the Hostess title.

The DCS Concept

The origin of the DCS position at TWA dates back before the widebody era, and can probably be credited to the Director – Passenger Service (DPS) at Continental Airlines, a position that began with that carrier’s Boeing 707 “Golden Jet” service in 1959. The position was somewhat different, in that the DPS actually collected tickets on board. With Continental’s “instant boarding” program, passengers were able to board a flight without a ticket and purchase one after departure. It is not clear how much authority the DPS had over the four “hostesses” in the cabin, but the position was heavily marketed in Continental’s print advertising and included reference to the fact that he had his own “radio-telephone” system available to make airline, hotel and car rental reservations.

TWA looked at the concept and briefly tested it on 707 flights, but decided against implementation. In the late 1960s, Pan Am also tinkered with the idea, in preparation for the 747s then on order. Read about its test program at: PAA Service Representative

TWA entered the widebody jet era as the second carrier to begin 747 service, following Pan Am by only a few months. With this huge airliner that more than doubled passenger capacity over that of the 707, a decision was made to add a new cabin attendant position; enter the Flight Service Manager. On international flights, the Purser position remained as well. Early TWA 747 flights were, to put it kindly, a bit disorganized. After a few months, it became obvious that the transition from narrow to widebody needed more than an upgraded Purser to pull it all together. Enter the DCS.

Fort Breech

My class, 71-2, was the second of the year, following six courses in 1970. It was made up of 15 “candidates,” another way of saying that our jobs were dependent on successfully completing the training. The class included several furloughed pilots who were able to maintain their TWA tenure in what was obviously planned as a holding pattern until returning to cockpit duties: Bennie Clay, Doug Heggie, Bill Hoar, Jud McLester, Hap Nairn, Bob Schulz and Jack Thal. Ernie Lorenzen and Anne Duffy had been Pursers; Nancy Harvey was a Hostess. Ron Jagen came from a long tour of duty in airport operations at Newark, while Bruce Megenhardt cut his teeth as a Transportation Agent and PRR at Los Angeles. I already knew Bruce, from passing through LAX so much, and had interfaced with Ernie Lorenzen during my days in New York.

Class 71-2. Top row (left to right): Bob Schulz, Ron Jagen, Bennie Clay, Doug Heggie, Bob Beehan, Hap Nairn, Jim Tollefson, Jud McLester. Front: Bill Hoar, Jon Proctor, Ernie Lorenzen, Nancy Harvey, Anne Duffy, Jack Thal, Bruce Megenhardt. My face was, for whatever reason, retouched over the right edge of my mouth.

Breech Academy was made up of several buildings, surrounded by a fence, hence its nickname, “Fort Breech.” Our double sleeping accommodations were pre-assigned; Hap Nairn and I became roommates. Our group occupied one complex of rooms, which surrounded a common area, known officially as the “living and learning center,” a name that was often amended; use your imagination to come up with the possibilities.

Each of the living centers featured rather gaudy decors. I don’t remember which one we were subjected to. Perhaps that’s for the best!

Training was intense, consisting of long class hours, evening study and short weekends off. For those wanting to go home (all of us), it meant riding on a pass, space available. With such a large TWA population in Kansas City, it was quite a challenge to get out of town on Friday evenings. According to my logbook, I often bought half-fares (positive space in those days) up to Chicago, where hourly flights to New York-La Guardia were easier to find seats on.

Much of our initial instruction concentrated on the flight attendant job. We become emergency-qualified in order to occupy cabin jumpseats, and learned all about meal services, galley layouts and procedures, as well as flight attendant and purser contracts, and even got into grooming. Serving “toy food” to each other in the cabin trainers became rather entertaining, especially for Anne, Nancy and Ernie, who already knew the procedures backwards and forwards. Everyone had to jump down the 747 evacuation slide, out of the cabin mockup and into the adjacent parking lot. In the pool, we inflated rafts, plopped in and out, and erected canopies. Back in the cabin trainer, door and emergency exit procedures were reviewed. An interesting class was conducted on how to service malfunctioning movie projectors and multiplex systems; more on that later.

This is a different DCS class, but they’re operating the same 747 door training in the Breech cabin mockukp.

Our job description was dissected in detail. As a member of management, we were to oversee the cabin crew while remembering that the captain was ultimately in charge; diplomacy would be critical to our success. But before each flight, it was our responsibility to visit the dining unit or caterer, inspecting every piece of dining and commissary equipment including food and drink. This interface was to give us an opportunity to provide feedback to those responsible in that area. After conducting a crew briefing, we were to meet the gate agents, their supervisors and even the station mangers when necessary. Again, diplomacy was required in order to develop good working relationships with these people, not easy when we had to give them negative feedback about earlier flight problems.

Once in-flight, we were to offer passengers assistance with future airline, hotel and car rental bookings in addition to cabin service oversight. After arrival at our destination, the DCS accompanied passengers to the baggage claim, or help staff service counters in Customs to assist as necessary. Various reports were to be filed at the end of trips, rounding out long days.

We spent a week becoming familiar with tariffs, multiple-destination fares, ticket writing, follow-up with reservations back on the ground and all the other things that our ground people dealt with on a daily basis. During this week of training it was time for Bruce and me to laugh at those in the class who had no clue how that all worked. But members of the group took each other under their wings, lending their expertise to those who needed it. The result was a close bonding among us.

Leadership was a big part of our training. We conducted mock crew briefings and interfaced with each other where one took the part of an up-tight passenger, flight attendant or, Heaven forbid, an angry captain. This is where the pilots in our group provided valuable input.

Out to Observe

During the fourth week, we were sent out on 747 observation flights under the tutelage of a working DCS. On August 16, I jumped on board Flight 708 at Los Angeles and rode to JFK with Bill Nelson, by now a seasoned DCS, having been in Class 70-3. Bill already had 20 years of TWA service under his belt. After a quick overnight in my Manhattan apartment, I flew back to LAX the next morning on Flight 7, with the legendary Bob Anderson. A natural salesman who came from the ranks of TWA sales reps, Bob excelled at stealing business from the competition. In the way of an introduction, Gate agents supplied each DCS with a list of passengers who had continuing or return reservations on a TWA competitor. In turn, the DCS used his or her persuasive talent in an effort to convince the passengers to change to TWA. DCSs had “free-sale” authority to confirm reservations on any TWA flight. On arrival, the information was phoned to reservations and seat assignments were procured. Similar authority was provided for room reservations at Hilton International hotels, which TWA owned at the time, and we had the ability to book car rentals as well.

Capable of selling refrigerators to Eskimos, Bob Anderson used his magic to a level probably unmatched by any other DCS, except perhaps Joe Brown, another former TWA sales rep; Steve Ching was in that category as well. On Flight 7, Bob told me straight away that he had flown with the cabin crew all month and they needed little or no supervision. Taking advantage of that, he showed me more revenue-stealing tricks that I could possibly learn by myself. For example, a woman and her three children were to overnight at Los Angeles, then travel to Hong Kong on BOAC. Bob convinced her to switch to TWA, based on the fact that BOAC was not showing movies on its flight (a VC10 that had no such equipment), while TWA was. The children would be entertained all the way across the Pacific with the in-flight entertainment; our competition never stood a chance. People like Bob helped turn the DCS program into a profit center; we routinely brought in more revenue than our equivalent salaries.

After taking care of the last passengers at the LAX baggage claim area, I had a couple of hours to burn before catching Flight 96 back to Kansas City. Rather than sit around, I followed Bob over to Satellite 2, occupied by Pan Am and the international carriers. There he produced several ticket coupons that he had taken in exchange for TWA tickets written on our flight. Overseas airline tickets so exchanged needed endorsements from the issuing carrier in order for the re-issuing airline to receive payment. Needless to say, competitors did’t take kindly to anyone pirating their customers. I wondered how Bob would handle this delicate situation. Silly me for thinking it might be a problem.

As we approached the BOAC counter, a smiling agent immediately greeted Bob by name, like a long-lost brother. Tickets from the family of four were quickly endorsed with validated stickers. Then, the agent produced a few TWA tickets that needed similar endorsement. Bob took out his portable validator and affixed the applicable stickers. Call it what you will: honor among thieves, tit for tat or just “quid pro quo.” Bob’s personality and old interline friendships made the day. Seeing me off on Flight 96, he offered, “I hope I was able to give you some insight.” Indeed. I was awestruck.

Graduation and Baptism of Fire

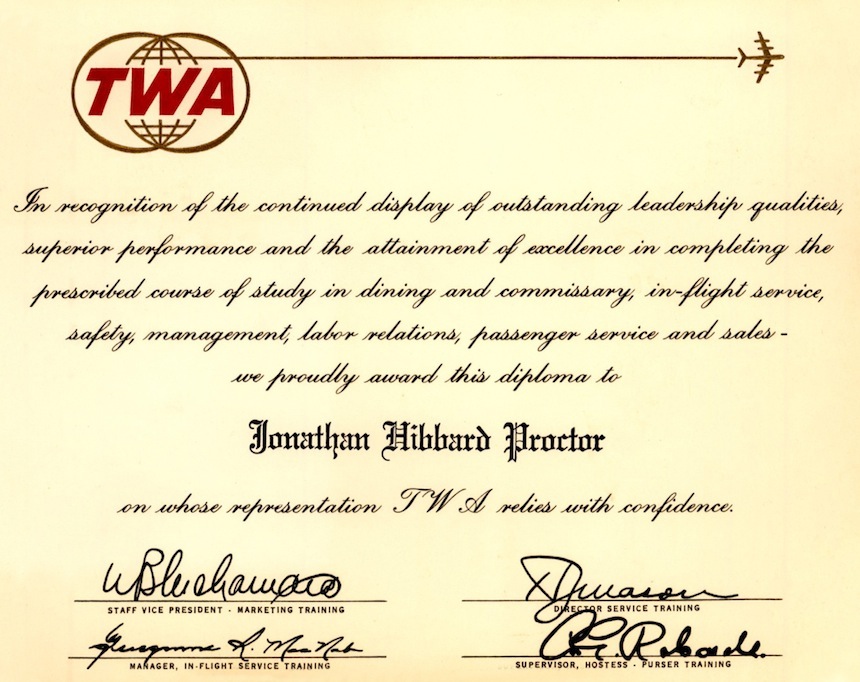

On August 26, all 15 of us in Class 71-2 graduated in a ceremony at Fort Breech. That night, we were treated to a celebration dinner at a local restaurant and given a few days off before reporting to our JFK domicile, for duty beginning September 1. The next morning, I flew back to New York via Chicago; it was great to be home for more than one or two nights in a row.

On August 26, all 15 of us in Class 71-2 graduated in a ceremony at Fort Breech. That night, we were treated to a celebration dinner at a local restaurant and given a few days off before reporting to our JFK domicile, for duty beginning September 1. The next morning, I flew back to New York via Chicago; it was great to be home for more than one or two nights in a row.

Following indoctrination at the domicile, Bennie Clay and I were assigned to observe our first trans-Atlantic trip, Flight 904 to Madrid on September 1. The working DCS, Bill Price, gave us a crash course on Customs formalities, lots of additional paperwork and the ins and outs of international flying. We had a heavy load, 17 in first class and 281 economy customers. It was also my first visit to Spain, which immediately became one of my favorite destinations. Six days later, I was on the same trip, which became my first solo DCS assignment.

Our domestic 747s were staffed by the Flight Service Manager and anywhere between 10 and 12 flight attendants. The FSM was the ranking union member in the cabin. On overseas trips, we also had a Purser, basically in charge of the first-class cabin.

The best part of my new job was the schedule, 3 days on, 3 days off, although there were occasional domicile meetings in between. In October, I drew London trips, again 3 on, 3 off. This became another favorite layover destinations, made easier by fewer language barriers and my familiarity with the city.

The Dreaded Flight 840

In November, I drew one of the more desired schedules, London “double crossings,” 6-day pairings operating New York-London-Chicago-London-New York. It amounted to only three trips for the month; very nice.

But when I checked in for my first trip, I had been suddenly reassigned to work Flight 840 to Rome, Athens and Tel Aviv. There was a special one-day qualification course for DCSs assigned to this trip. Group Supervisor Bill Whitaker pulled me into his office and gave me the full qualification in less than 30 minutes.

Flight 840 operated a daily schedule from Los Angeles to Tel Aviv, with intermediate stops at JFK, Rome and Athens. A LAX crew brought the 747 to New York, where a JFK crew took it on to Rome, a layover point for everyone. While the JFK cabin crew returned to New York the next day, a Rome-based cabin crew worked the flight down to Tel Aviv, along with the DCS and JFK-based pilots, then returned to Rome the next morning, again via Athens. On the fifth day, the same pilots and DCS returned to New York with another JFK-based cabin crew. Are you following me so far?

The Rome-based cabin team had a Purser, but no FSM, and worked under work rules that differed from U.S.-based employees. In addition to food service on both European segments, much more duty-free sales were conducted. These were short, but very busy flights.

Flight 840 was notoriously late. If it wasn’t delayed while transiting JFK in rush hour traffic, there were multiple opportunities for backups at Rome, where labor strife was almost constant. Add to this a relatively short overnight Tel Aviv layover and you had the ingredients for problems, lots of problems. My logbook tells me this trip was typical. We were 1 hour, 30 minutes late leaving JFK; the flight apparently cancelled at LAX or was so late we didn’t wait for it, and re-originated as Flight 6840 with another 747. Two days later, leaving for Rome, the flight was 7 hours, 30 minutes late, owing to a mechanical problem, which mandated a 1-hour delay the next morning to allow for minimum crew rest. Incidentally, DCSs had no minimum rest rules!

Finally, on Day 5, we returned to JFK with 248 passengers, this time 2 hours, 30 minutes late with yet another mechanical issue. A late arrival at JFK presented major headaches for customers, and in turn, for the DCS, especially when coming back from overseas. Upon arriving from Rome, a delay of more than 2 hours meant the majority of our connecting passengers would miss their onward flights. Not all were changing at JFK, but nevertheless there more than 150 “miscons,” overwhelming the service desk in Customs, which was dealing with multiple inbound flights. It meant an extra hour or more of duty time for one tuckered-out DCS. London flights never looked so good.

747 Teething Problems

I should pause here to relate some of the challenges we faced as an early 747 operator. “Bugs” were still plaguing us more than a year after putting the type into service.

Chief among the headaches were those big JT9D engines. Overheating occurred during start-up when wind was allowed to blow up the tailpipes. If the temperature exceeded a certain level, a time-consuming boroscope inspection was mandatory and often resulted in a flight cancellation. Engine changes were not uncommon and we often carried an extra one across the Atlantic, either to replace a damaged power plant or bring one back for repair. Slung under the wing between the No. 2 engine and fuselage, its added weight diminished our payload and could result in airspeed restrictions.

But for the DCS, the main headache was the multiplex, or “Mux” system, a single-wire transmission arrangement between the reading and passenger call lights, along with the cabin interphone system, 600 pounds lighter than the conventional systems on our 707s. It also controlled the audio entertainment system that provided movie soundtracks and music via passenger headsets. Relay boxes for the Mux system were fitted under certain rows of passenger seats, easily jarred by carry-on luggage and the passengers’ feet. System overheating could cause the lights to blink on and off for long periods of time, especially unpleasant on night flights.

In such cases, shutting down the lighting in entire passenger zones was about the only solution, with hopes that the system would cool down and operate normally when restarted. “Runaway bells” were especially irritating, often solved by snipping a few strategic wires, something we were expressly forbidden to do, but often did in order to prevent passenger uprisings.

The first-generation movie projectors were stowed in cabin ceilings and could be lowered via an inertia-reel system, but only after clearing passengers out from under the compartment. This became necessary when the projector light burned out or the film actually broke, a not uncommon occurrence. A piece of cellophane tape would repair the film, provided you could find the two ends. If the projector was not immediately turned off, lowering the housing usually produced a spaghetti-like shower of film, tangling into an impossible pile on the cabin floor. When this happened, it was time to start refunding movie headset rental fees.

No, that’s not a 6-engined 747 about to depart fom London. Under the wing, close to the fuselage, an extra engine is stowed for transport back to the U.S. for repairs. ©Jon Proctor

The lavatories were another challenge early on, in the form of foul odors from the toilets. After studying the problem, Boeing engineers determined that fecal matter was sticking to a portion of the toilet motor that got hot with repeated use and warmed up the poop to a rich aroma. Until a modification could be implemented, it was standard procedure to empty a 5-pound bag of ice cubes in each of the 14 toilets just prior to departure. This solution was only marginally successful in solving the outhouse effect. Even deodorizers were of little help. When a lavatory became too rich to enter, it was locked off and the waiting lines grew longer.

The passenger doors were equipped with a sophisticated system to automatically deploy the combination escape slide/life raft. On departure, moving a handle on the door from one position to another armed the system and the procedure was reversed on arrival. As a safety measure, the arrangement was designed so the slide raft would not deploy when the door was opened from outside. This was to avoid inadvertent activation that could seriously injure ground employees meeting the flight if someone forgot to disarm the door. But if it was accidentally opened from the inside while armed, an automatic assist system would push the door completely open and the next sound would be hissing of compressed air as the slide raft inflated. This occurred on a much-too-frequent basis until cabin crews got more familiar with the procedures and the door mechanisms were modified to keep them from sticking in the armed position. Meanwhile Flight Attendants were obliged to get down on their hands and knees and raise the housing cover to visually verify the correct configuration.

Double Crossings

After a 5-day break following my Tel Aviv adventure, I left on my first double crossing. The summer peak travel period was over and loads dwindled. I departed on Flight 700 November 15 with only 15 first-class passengers and 97 in the back. FSM Jim Puglise was one of the best I flew with, allowing me to concentrate on stealing passengers, but with this load, there were not many return reservations to plunder from the competition. Following a 28-hour layover in London, we headed to Chicago on Fight 771, carrying a total of 118 customers, barely one-third of the 747’s capacity. Winter weather brought stronger winds across the Atlantic; translation: fast eastbound rides and longer returns to the west; it took us 8 hours, 26 minutes to reach O’Hare Field. The pattern then reversed on the following evening, and finally back to Heathrow and home to JFK; 22 time zones transversed in 6 days.

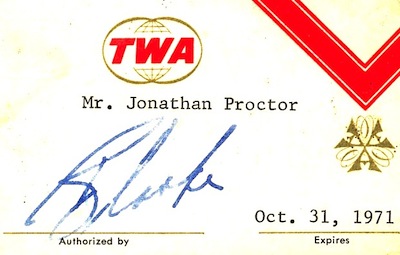

These Ambassador Club cards were passed out to us upon graduation at Fort Breech, albeit with expiration only two months later. We got new ones thereafter and were expected to strictly limit their use.

I only had one more trip for the month, departing on November 25, Thanksgiving evening. Our flights to London and back to Chicago were routine, with light loads. The fun began on the return to Heathrow, where the airport was fogged in. Making one pass at the field, we could see the control tower cab but the rest of the airport was covered in white. The forecast called for improving conditions within an hour, but we didn’t have enough fuel to hang around, and proceeded to Paris, where Polar Flight 760 had also found a safe haven. Two hours later, it was back to Heathrow and circling for another two hours before finally landing.

On Day 6, the crew was looking forward to heading home, but upon arrival at the airport, we found that the airplane had developed a mechanical problem. The passengers were protected on our second New York flight and we headed for lunch at the employee cafeteria. Within an hour, the 747 was repaired and set up to operate a ferry flight to Madrid. Operational Planning in New York had canceled that evening’s JFK-MAD trip so our airplane was needed for the return to back to JFK the next day. “Tasca (bar) hopping” in Spain seemed like a nice diversion and off we went. Bill Judd, one of TWA’s finest captains, gave us a 1-hour, 40-minute aerial tour and running commentary as the empty jumbo migrated south. Madrid tonight, home tomorrow, no problem.

But wait. Upon arrival at Madrid, the TWA agent meeting our flight handed the FSM a revised schedule for the crew. We were not going home the next day; there was already a crew in town from a day earlier. Instead, we would spend two nights Tasca hopping, and go home on Day No. 8. FSM Sal DiGoia immediately organized an underwear-washing party in the a suite he had procured by bribing the hotel concierge with a carton of cigarettes. The master bathroom tub was filled with hot water and hair shampoo, whereupon everyone tossed their undies in and let them soak, while we sucked up copious amounts of Sangria and hors d’oeurves brought up from the hotel bar.

On Day 7, some of the crewmembers toured Seville while others either sunned themselves on the rooftop deck or just rested. Finally, on Day 8, Flight 903 brought us back to JFK, tired but happy to be home.

Christmas in London

I guess my two trauma trips in November convinced DCS scheduler Norm Kitzmiller to smile upon me with another month of London double crossings. Even though I was scheduled to spend Christmas in England, an earlier planned New Years in Zermatt, Switzerland with brother Dick and family would still be possible. I departed for Heathrow on December 21 and completed three legs without incident, arriving back in London on Christmas morning. Although the DCS normally stayed at an airport hotel, there was a married couple among the cabin crew, and FSM Ed DeVictoria, another TWA legend, arranged for me to get my own room downtown with the rest of the crew.

Two Sky Marshals on the trip were with us in the same hotel. Both in the military reserves, they invited us to join them at the Columbia Officers Club in London for Christmas dinner. Imagine being in a foreign country and sitting down to a traditional turkey dinner with all the trimmings, at a ridiculously cheap price that included lots of wine; it was great evening and I only wish I had taken some pictures.

I was anxious to get back to New York on December 26, as I planned to fly to Switzerland the following evening. But back in London, the usual crew call from Operations brought the news: our flight was cancelled and we were going to spend an extra night, returning to JFK on the 27th. I had already arranged to meet my brother and family in Switzerland on the 28th. They were on the road and there was no realistic way to contact them. It left me only one option.

Day 7 brought us home to New York as rescheduled. After completing DCS duties, I headed back to my apartment, repacked bags and returned to JFK in time to catch KLM Fight 642, a 747 nonstop to Amsterdam, connecting with a DC-9 flight to Geneva. A train then took me to Visp, at the foot of the mountains, a previously agreed upon meeting point with Dick and family, but they apparently had been delayed and were not there. To say I was beyond exhausted would be an understatement. I decided to check into a hotel and head to Zermatt the following day. It was early afternoon, and I asked for a 6 o’clock wakeup call before collapsing into a hard, deep sleep.

My call came as scheduled; it was dark out and I was hungry. After taking shower and cleaning up, I went down to the dining room, where a smiling waiter handed me a menu, which, fortunately, was in English. But nothing appealed to me; why would I want an omelet for dinner? I asked for the evening menu and was told the shocking truth: dinner is not served at 7 a.m. The front desk clerk must have assumed I wanted a morning wake-up call. I had slept for more than 18 hours straight.

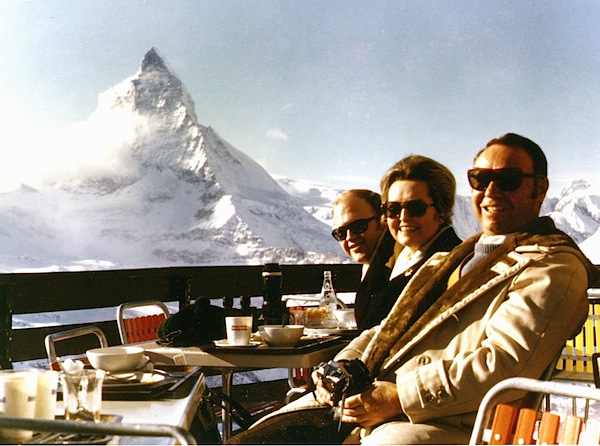

After breakfast, I packed and rode the train up to Zermatt, where Dick and family had already arrived; we exchanged travel stories and I won for the most unbelievable. New Years in that storybook setting was perhaps the most memorable of my life, spent with Dick, his wife, Lucy and grown children Penny and Rick, filled with ice skating and a gondola ride to a spot with tremendous views of the Matterhorn. After four days, I hated to leave.

Following a night in Geneva, I intended to take a TWA flight back to JFK, but it was well oversold, so instead I purchased a 75% reduced-rate ticket on Swissair to London. The counter agent told me the flight was completely booked and I would probably not get on, but a kind Swissair gate agent found a seat in first-class with my name on it. At Heathrow I caught TWA Flight 703 back to JFK. Because of the holiday schedule, it was operated with a 707, but I still got a first-class seat, right behind an attractive young lady named Caroline Kennedy.

I did some time in the office in January and February, working on various projects, and only flew two London double crossings and a Madrid trip, then got a another taste of Flight 840, with two trips in March, along with a 3-day Frankfurt pairing. Having already accumulated some vacation time, I squeezed in a trip to Hong Kong as well.

Charlie Schimpf

Sometimes you meet someone who is truly in love with his job. One of them at TWA was FSM Charlie Schimpf, a German, needless to say. He’s in the Guiness Book of Records for the most trans-Atlantic crossings; 2,880 between March 1948 and September 1984. Now that’s some serious time aloft.

Charlie was the consummate leader and professional, while at the same time a constant joker on the public address system, within reason. He always got away with it; the passengers and crews loved him. One of his favorite smile-makers was to announce items left in the lavs; use your imagination, as did Charlie. He had a great sense of when he could pull off that stuff and when no one else would dare try. I was on one trip with him and heard not a wisecrack, joke; nothing. I asked, “You okay, Charlie? Why no jokes?” He had a simple reply: “Wrong audience, Jon.” What a remarkable guy; I really enjoyed flying with him.

Here’s Charlie, circled in a picture from the June 22, 1961 TWA Skyliner; his last name is misspelled in the caption. I wish I had a better picture.

Upon reading this chapter, retired TWAer Doug Annett wrote to me:

Charlie was on of my most favorite TWAers when I worked at JFK Crew Schedule. I wanted to share with you this special story

When I was a new hire back in late 1961 or early 1962, I signed myself and my parents up for their first trans-Atlantic crossing, on one of our global European tours. I told my folks that we were space available and if, for any reason, we were asked to deplane that we needed to do so quickly and quietly.

We boarded a Boeing 707 at Idlewild for London and Charlie Schimpf was our purser. He knew we were on board, seating in coach. Just after the boarding door was closed, Charlie came back through the cabin looking very perplexed and stopped at our seats. He promptly demanded that my dad produce our boarding passes, then proceeded to sternly proclaim in a loud tone, “These are not your seats! Please follow me.”Convinced that we were being asked to deplane Dad promptly gathered all our belongings and followed Charlie forward as directed, with Mom and I close behind.

Upon arrival in the first-class cabin, Charlie broke into a smile and said to my dad, “You and Mrs Annett sit here and Douglas, you sit across the aisle.” He then entertained all of us in first-class with has fantastic sense of humor, topped off by an exquisite Royal Ambassador service. I will always remember his incredible personality and the kindness he extended to my folks. Mom and Dad never forgot their first TWA experience, thanks to Charlie.

The last time I saw Charlie was at Wilkes-Barre in the late 1980s, when the restored 1049 Constellation, then operated by Save-A-Connie, was at an air show. Long-since retired, Charlie lived in the area and came out to see the airplane. I can remember him saying how small it felt when he went through it, after so many years since flying the Atlantic in props.

There were other outstanding FSMs, like Wally Janssen, Jimmy Astudillo, Fred Duss, Deiter Ruf and Guenter Zoeller. These and others stick in your mind; they were the greatest.

“I’m Going to Blow up the Airplane!”

With the L-1011s coming in June, plans were afoot to open a DCS domicile at Chicago, where all the initial TriStar flying was to be based. Until then, there was an ad hoc DCS base in place to cover a daily ORD-Las Vegas turnaround, plus overnight trips to LAX and San Francisco. Five DCSs covered those trips: Penny Donahue, Dale Kreimer, Hank Krueger, Bob Henderson and Bob Green.

Chicago had been a domestic flight attendant domicile since early on, incidentally. Bruce Megenhardt tipped me off to the fact that two more DCSs were needed to fill in at ORD until our base was to open in June. We decided to volunteer with hopes of getting in on the ground floor.

I left on my first trip with an ORD-based crew on April 21, a 2-day pattern to San Francisco, departing on the continuation of Flight 771 from London, coming back on the origination of Flight 770 the following day. FSM Judi Gitz and her crew were kids in contrast with the more senior JFK crews, and exhibited a good deal of enthusiasm.

We departed 2-1/2 hours late, owing to a mechanical problem. Many of the 109 passengers were coming through from London, and stretched out across multiple seats to sleep, some without even having dinner. All was peaceful and quiet until less than an hour before we expected to arrive in San Francisco, when a flight attendant came up to me with a serious look of fear on her face. “There’s a passenger back there who says he’s going to blow up the airplane!” Oh, swell.

It seems a German merchant seaman had apparently over-indulged in drink and decided to make a name for himself, telling the flight attendant that the airplane would “blow up like a crescent,” and that he had the bomb in his travel alarm clock, which he showed to her. By the time I got back to confront this man, he had passed out and the very common, small clock lay on a seat next to him. I took the clock, then went to the cockpit with the bad news. Captain Jim Lydic did not hesitate. We would take the threat seriously and he instructed me to let the man sleep while we proceeded to our destination.

The Chicago-based cabin crew on one of my trips. Unfortunately I didn’t get all the names, but that’s FSM Judy Gitz in blue. De Pilgrim is standing, third from left, next to Wicktor Bachaeuretz, then Carmilla Dean. Judy Petersen is in front, left, next to Sharon Kosko. ©Jon Proctor

It was decided to park at a remote location at San Francisco airport and deplane passengers via a single mobile stairway. I was to be at the door and identify the mad bomber to authorities. When we arrived, an FBI agent, fluent in German, was standing on the steps, along with two other law officers. Sitting in the very back of the aircraft and among the last to deplane, the offender was promptly handcuffed and taken into custody. The Captain, FSM, one Flight Attendant and I were interviewed briefly and gave written statements. Except for those witnessing the arrest, none of the passengers had any idea what was taking place, although we did make the local newspapers a day later.

I flew with the same cabin crew all month, and some of the same flight attendants again in May. Meanwhile Bruce and I interviewed with ORD General Manager – Inflight Services Diane Croll and newly appointed DCS Manager Ralph Wilson. Both of us were invited to come to Chicago permanently.

In retrospect, I think every young person should have the chance to live and work in New York, specifically Manhattan, with great restaurants, parks, transportation and the arts. I would not trade those experiences for anything, but I was ready for a change; it was time to move on.