1977 – Overseas Assignment

Saudia jumbo OD-AGH, better known to us as “Golf-Hotel,” receives attention at Cairo between flights.

Click on individual pictures for an enlarged view.

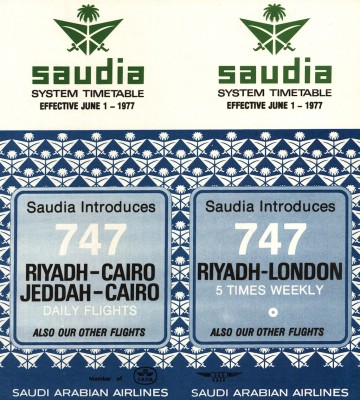

By May 1977, my former boss, Bill Borden, was Director of In Flight Service Programs in the corporate offices. Shortly after I returned from Kansas City, he called to welcome me to the flight attendant ranks. During the conversation, Bill asked if I knew that Saudia – Saudi Arabian Airlines was offering 18-month contracts to TWAers with widebody jet in-flight supervisory experience, in conjunction with that carrier’s implementation of its first 747 flights; there were 12 openings. Successful In-Flight Supervisor (IFS) candidates were to be based at London and those on active flight attendant status would retain and accrue job and pay seniority.

No, I didn’t know about this and yes, I was interested, very interested.

April 12 found me back in Kansas City for a board interview with Saudia management and two TWA supervisors already on assignment at the Jeddah base, flying L-1011 trips. These new positions were to become effective May 1, so we were told to expect a decision on successful applicants within a week.

In the meantime, I began as a flight attendant two days later, on reserve status, also known as “flying the telephone.” The first assignment came on my 31st birthday, April 18, a nice two-day San Francisco L-1011 trip. After a few days off, I entered the real world with a four-day Boeing 727 pattern. The last duty period was, basically, an all-nighter leaving San Francisco in the early evening for New York, with stops at Los Angeles, Albuquerque and Chicago. On the initial segment, I had the pleasure of serving Dick Tewell, my first TWA boss, who was on his way home from vacation. Sadly it was the last time our paths would cross.

Departing from O’Hare at 6 a.m. the following morning, this businessman’s special featured a full load and hot breakfast service. By then, my body clock was still somewhere west of the Rockies in a deep-sleep mode. Working in coach, I sat on the back jumpseat as we encountered an ATC delay in the New York area, trying to just stay awake. Driving back to Connecticut was an even bigger challenge.

I slept until late in the day, awakened by a telephone call from TWA’s employment office. I’ve forgotten the woman’s name, but after verifying my identity, she exclaimed, “Pack your bags; you’re going to London!”

TWA crew scheduling nabbed me for one more trip two days later, working a DC-9 flight to Indianapolis and deadheading home.

London Base

I officially belonged to Saudia as of May 1 and flew back to Kansas City once again for an informational briefing by our industrial relations people, covering Saudi Arabian laws and the airline’s policies. Considerable time was spent explaining restrictions on liquor and pornography; read: Playboy Magazine is considered to be pornographic! We were required to sign statements acknowledging our understanding of these restrictions (Foreign Laws Agreement) and also asked for verification of our Christian religions, in the form of a baptismal certificate or confirmation of church membership.

I officially belonged to Saudia as of May 1 and flew back to Kansas City once again for an informational briefing by our industrial relations people, covering Saudi Arabian laws and the airline’s policies. Considerable time was spent explaining restrictions on liquor and pornography; read: Playboy Magazine is considered to be pornographic! We were required to sign statements acknowledging our understanding of these restrictions (Foreign Laws Agreement) and also asked for verification of our Christian religions, in the form of a baptismal certificate or confirmation of church membership.

We were paid an amount equivalent to that of a TWA in-flight supervisor plus a premium, and were considered management employees, hence the return of my coveted TWA term pass for unlimited space-available travel. While working for Saudia, paychecks came from TWA and were direct-deposited into our U.S. bank accounts. Expense money was to be issued in the form of a check from Saudia, payable in Saudi Riyals, to be cashed during our layover time in the Kingdom. Each of us was granted a generous one-time baggage allowance for shipment of personal items and a $3000 lump-sum payment in lieu of housing. Many used it for apartment rental deposits or to buy a car. Finally, a term pass for unlimited travel on Saudia was issued; something I never had occasion to take advantage of; back then the carrier did not fly to the U.S.

There was enough time at home to rent out my Connecticut condo and sell my car before dutifully boarding TWA 747 Flight 700 on May 3, bound for London-Heathrow (LHR) and my new assignment.

I had met the other successful candidates at one time or another. They were: Gil Bernal, Ray Campbell, Gordon Humpherys, Svein Husevold, Allan Johnson, Paul McGowan, Frank Messina, Clive Miller, Bob Trotter, Bob Van Well and Jerry Warkans. At the last minute, Tom Donahue replaced Clive Miller. Ironically, British-born Clive was declared ineligible because he lacked an American passport, necessary to comply with the U.K. resident work agreement.

My friendship with Bob Trotter went way back to 1965 when we met during a TWA customer service training conference, then worked together at the Kennedy Space Center and were based at Chicago as DCSs along with Tom Donahue and Svein Husevold. Paul McGowan and I had become flight attendants a month earlier and knew each other from the JFK DCS domicile. Everyone else had served in the DCS ranks at one domicile or another. Frank Messina had earlier “done time” as a Jeddah-based IFS; Allan Johnson transferred from Jeddah to London.

While Saudia for some time had maintained a hostess domicile at London, the IFS group was Jeddah-based until we invaded England. One of the challenges was a different tax code in the U.K., requiring that we spend at least one month per year in country. To meet the standard, each of us would complete 30 days doing office duty annually. There were to be 10 flying schedules, one reserve IFS and one office-bound.

Seen in its classic “Cedar Jet” livery before repaint in Saudia’s colors, this 747-2B4B would be one of my two in-flight offices for the next 18 months. The photo comes from my collection but I didn’t take it.

At the time, Beirut-headquartered Middle East Airlines (MEA) was coping with the ravages of a civil war in Lebanon that began in 1975. In order to survive, much of its fleet was leased to other carriers and based out of the country. Two of the three 747s were to be leased by Saudia for flights between London and Riyadh plus service within the Middle East. In order to preserve jobs, airplanes were “wet leased” when possible, maintained and staffed by MEA employees. For this contract, two London-based Saudia hostesses and a Jeddah-based Saudi purser would supplement MEA cabin crews of 15 or 16, depending on the segment flown. MEA pilots rounded out the crew. Throw in an American IFS and you had a regular potpourri of nationalities and diplomatic challenges.

Allan Johnson taught Saudia procedures to MEA cabin crews in Beirut just before joining our group, so had good insight about what we were in for when it came to dealing with Lebanese culture. He then instructed us on the same policies during 10 days of classes conducted in the Heathrow Hotel at London Airport, where we were provided housing through the end of May.

Most of the instruction revolved around serving procedures. Except for the absence of alcoholic beverages, first class would be nearly identical to what we were used to at TWA. In the back there were to be no serving carts in the aisle. Instead, soft drinks and juices would be offered from serving trays, followed by the meals, hand-delivered from the galleys. This simplified service was in stark contrast to MEA’s procedures. Everyone wondered why 17 or 18 people were needed to carry it out, but we didn’t ask.

Safety instruction consisted of differences training between MEA and TWA 747s and license certification according to Lebanese government rules. We were able to get Heathrow Airport ID badges and obtain United Kingdom multiple-entry work visas relatively easily.

Maryfield Estate in Taplow included “Maryfield Orchard,” the attached red-brick structure on the right, which Allan Johnson and I rented.

Looking for housing was more of a challenge. Most of us roomed together to help cut down on costs, as rents were fairly steep. I was most fortunate to link up with Allan Johnson, who had located a two-story coach house less than 30 minutes west of the airport in the Thames Valley, on the estate of Leonard and Sally Miall, in the small town of Taplow Village near Maidenhead. Named “Maryfield Orchard,” it featured an American kitchen, two bedrooms and a spacious living room (“lounge”). From upstairs, we had a sweeping view of the valley and could see Windsor Castle in the distance. I found out later that Mr Miall had a fascinating background. He was a war correspondent for the BBC during World War II who first reported on the significance of the Marshall Plan. Click here for his story: Leonard Miall.

It didn’t take much car shopping before I decided to rent one instead. Flying Tigers offered a $100, space-available car transport to airline employees, and Ray Campbell actually brought his vehicle over, but I had sold mine in the States and, in any event, was afraid of driving on the left side of the road in England with an American car. Our flight schedules allowed for some extended time off and airline discounts on rentals made the option much more attractive to me. The car rental offices were a short walk from the Heathrow Hotel, where we were transported from planeside at the conclusion of our trips, so the whole process was easy.

A Trip to the Kingdom

L-1011 HZ-AHE, which took us to Jeddah, was originally delivered to TWA and sold straight away to Saudia. Dean Slaybaugh photographed her at Kansas City shortly before she departed for the Kingdom. Notice the mothballed Convair 880s in the background.

On May 13, nine from our group flew down to Jeddah (JED) to obtain Saudia ID badges, multiple entry-exit visas for Saudi Arabia and uniform fittings. Check-in for the mid-day departure was a preview of what we were to experience in our new roles. Passengers were lined up at the counter with luggage carts containing everything but the kitchen sink. It took nearly an hour just to get boarding passes. In the departure lounge everyone had a couple of stiff drinks in anticipation of a couple of“dry” days in the Kingdom. It was expected that we would only be gone two nights.

At the gate, passengers were jammed up against the boarding door and for good reason: Saudia did not assign seats in the economy section. We stood back and let a mad rush proceed, then boarded the L-1011 and still managed to find decent seating. The nearly 6-hour flight itself was uneventful. On TriStars, Saudia utilized in-aisle serving carts; the meal service was efficient and cheerfully completed. The sun set as we entered Saudi Arabian air space, with nothing but desert visible below. It was a time for personal reflection, contemplating what lay ahead.

Reality set in as I stepped off the airplane at JED. There were no covered Jetways to greet us and the hot, humid air felt like a sauna; I could almost see the crease disappear from my trousers. By the time we cleared Customs and walked out of the airport terminal, I was dripping wet with perspiration. We were to be met by a Saudia representative but no one showed up for nearly a half-hour. Then, finally, our appointed escort appeared and walked us to the Kandara Palace Hotel, little more than a block away; the airport was literally in the middle of town. Owing to a shortage of rooms, all of us had to double up, something we had been told to expect. The hotel was, to say the least, well worn, with tiny beds, hard mattresses and Spartan furnishings. Air-conditioning was marginally effective.

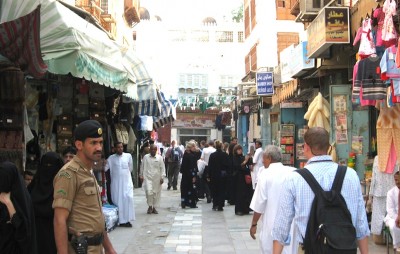

A web photo of the Jeddah souk. Although more recent, it pretty well represents the marketplace we often visited.

After dumping our bags and changing clothes, we met in the hotel lobby and walked to the souk, or marketplace, for a look around. Frank Messina was our guide and steered us to a Greek food cart for Gyro sandwiches. I was taken by the noise level as we walked around, loud conversations, all in Arabic of course. Frank taught us a few words, such as khalas (pronounced “ha-LAS”) or “finished,” to use when pestered by locals peddling their wares.

Our first stop the next morning was at Saudia’s headquarters, to obtain our company ID badges. “Malesh (Sorry), the camera is broken; come back tomorrow,” said the man in charge. Not to worry, we’ll got get fitted for our uniforms. “Malesh, closed today; come back tomorrow,” advised the man at the tailor shop. Then it was on to the Customs office at the airport for our visas. “There is a problem: you should not have had your passports stamped last night. We cannot do the visas.” Huh? A trip back to Saudia headquarters brought assurances that everything would be sorted out “by tomorrow.” Day 2 of our trip was a complete waste.

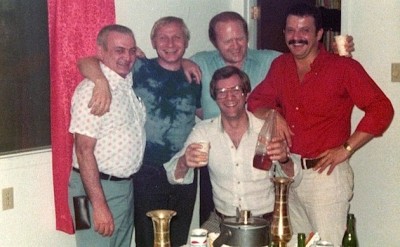

Sampling Sadiki on Day 2. Left to right: Ray Campbell, Svein Husevold, Yours Truly, Bob Trotter and Frank Messina. ©Jon Proctor

Three Jeddah-based IFSs invited us to their villa for dinner that evening. Briefly, we felt at home again, sitting in a prefabricated home (trailer) in air-conditioned comfort, enjoying cocktails, of sorts. Call it moonshine or whatever, the alcoholic beverage was better known as Sadiki (“my friend”), distilled by the ex-pats and tasting something like Vodka. The Saudi authorities were known to look the other way as long as it wasn’t distributed or sold to others.

Day 3 proved a bit more productive. During a brief meeting at Saudia headquarters I was reunited with Don Heep, who had greeted me on my first day with TWA at Los Angeles 13 years earlier. By then he had become Saudia’s general manager of marketing services. As always, I addressed him as Mr. Heep. Shaking my hand warmly, he smiled and said, “Jon, over here it’s just ‘Don,'” to which I replied, “Anything you say, Mr. Don!”

Uniform fittings were taken care of later that morning but again the ID badge camera was still inoperative. “It will be fixed tomorrow, inshallah (‘God willing’).” Then we were told that, in order to obtain multiple entry-exit Saudi visas, it would be necessary for us to leave the country, with passports stamped accordingly, and re-enter without having them marked, at which time the visas would be issued. So on Day 4 we boarded another Saudia TriStar and flew to Cairo (CAI) and back. The stopover in Egypt was just an hour but sufficient for us to consume two pints of lager in the transit lounge bar; at that point we really needed them!

Upon return to JED, there was a brief skirmish when officials tried to stamp our passports. Fortunately Frank Messina knew enough Arabic to explain our situation. We were referred to the Customs office and assured that the visas would be ready for our departure to London the next day. Reluctantly we left our passports so they could be so stamped.

Bright and early on Day 5, the group returned to the ID badge office yet again and rejoiced upon discovering that the camera was fixed. From there it was a short ride to the airport and check-in for SV173 back to London with a stop at Paris. But this was not possible until we reclaimed our passports. By now, you probably know what came next: the Customs office had not completed the visa formalities and told us to come back “tomorrow.” Again, Frank intervened and somehow the formalities were completed. We rushed back to the check-in counter, obtained boarding passes and reached the gate shortly before departure. A little over eight hours later everyone was in the Heathrow Hotel bar sucking up the suds.

Baptism of Fire

Golf-Hotel at Riyadh on its first day of service within the Kingdom.

At month’s end, several of us deadheaded down to the Kingdom to be in place for our first flight assignments. I was sent to Riyadh (RUH), which involved a connection at JED, arriving late at night.

At month’s end, several of us deadheaded down to the Kingdom to be in place for our first flight assignments. I was sent to Riyadh (RUH), which involved a connection at JED, arriving late at night.

In contrast to Jeddah, the city of Riyadh is inland, at an altitude of 2,000 feet, making it less humid but usually warmer. Our crew layover hotel was the Elkherji, a long way from the Ritz, believe me. Accommodations varied by room. Some had small fridges, others did not. Some had bedside table lamps while others didn’t even have bedside tables! All had small, single beds. As with the Kandara Palace in Jeddah, individual window air-conditioners provided a wide variety of cooling efficiency. Summer temperatures in Riyadh routinely exceeded 100°F and it was not uncommon to enter a sweltering room before the A/C was turned on and began giving limited relief. Hot water, when we had it, often came from the cold-water spigot because of the outside temperatures. These were to be our homes for countless layovers, both short and long.

An added challenge in the Kingdom was the Islamic calls to prayer, loudly “recited” (yelled out) five times daily over public address systems. They were especially irritating in Riyadh as the loudspeaker was attached to the outside of the hotel and close to our rooms, depending on which ones we occupied. Calls in the middle of the night were common. We quickly learned which side of the hotel the speaker was attached to and always requested “quiet” rooms, with only occasional success.

Jumbo-served routes were five-times weekly London–Riyadh (3069 miles), once-weekly Riyadh–Beirut (925 miles), and daily Riyadh–Cairo (1014 miles)–Jeddah (675 miles).

On my first full day at Riyadh I met the MEA cabin crew that were to work my initial trip. I liken the experience to house pets meeting for the first time, not at all sure of each other. It turned out I was blessed with an exceptionally good crew for my first trip, led by Head Steward Michel Khalifeh, who it turns out had been a champion water skier. Two Saudia hostesses from London and the Jeddah-based Saudi purser joined us the next morning and we launched for CAI and JED aboard 747 “Golf-Hotel,” officially registered OD-AGH. This jumbo, along with Gulf-India (OD-AGI), resplendent in Saudia colors, made up our jumbo fleet.

On my first full day at Riyadh I met the MEA cabin crew that were to work my initial trip. I liken the experience to house pets meeting for the first time, not at all sure of each other. It turned out I was blessed with an exceptionally good crew for my first trip, led by Head Steward Michel Khalifeh, who it turns out had been a champion water skier. Two Saudia hostesses from London and the Jeddah-based Saudi purser joined us the next morning and we launched for CAI and JED aboard 747 “Golf-Hotel,” officially registered OD-AGH. This jumbo, along with Gulf-India (OD-AGI), resplendent in Saudia colors, made up our jumbo fleet.

The two 747s were configured with 48 first-class seats on the main deck plus 16 in the upper deck, and 322 in economy. Although wearing exterior Saudia paint, the airplane interiors were vintage MEA and quite attractive.

Posing with Michel Khalifeh and his wife Hadia, on a Cairo ground stop during our brief dispensation from the wearing of ties in the Middle East; it was quickly rescinded only days later. ©Jon Proctor

Following a 25-hour layover back at the Kandara Palace, I reversed course to RUH, again via CAI. On the last segment, a young Egyptian woman boarded the flight in a wedding dress. One of the MEA hostesses told me she was a “purchased bride,” en route to meet her chosen husband in the Kingdom. A special cake was boarded for the occasion, and women seated around her shared the cake and sang songs in her honor. On arrival at Riyadh, the groom, who she had never met, greeted her with flowers. This was the first of several brides I came into contact with. Unlike the first one, others were not always met. I saw one crying in the arrivals area until someone finally led her from the terminal.

Saudia was growing exponentially and all departments struggled to keep up with its rapid expansion even before 747 operations began. The jumbos were an added challenge for the ground crews, especially at Riyadh and Jeddah. A new Riyadh Airport was under construction but not yet finished, and Jeddah’s replacement field was even further in the future. Both airports had painfully inadequate terminal buildings and relatively small ramp areas. Neither had Jetways.

To compound the problem, both 747s were often on the ground simultaneously at Riyadh. Departure delays became inevitable and frequent. With little scheduled time on the ground, the situation could quickly snowball.

On flights within the Middle East, there were numerous examples of more passengers boarded than seats available. Small children – and there could be as many as 100 on a single flight – were on occasion counted as infants, referred to as “lap babies.” We would have too many in seat rows without sufficient drop-down oxygen mask capacity, producing “musical chairs” to meet those restrictions. Lack of seat assignments exacerbated the problem.

Every flight included a meal service, however even on the shortest scheduled segment, CAI–JED, it was easy to complete. Unfortunately not all the crewmembers got along with each other and we even had occasional pilot disagreements although these were quickly resolved with diplomacy and nearly always in their favor.

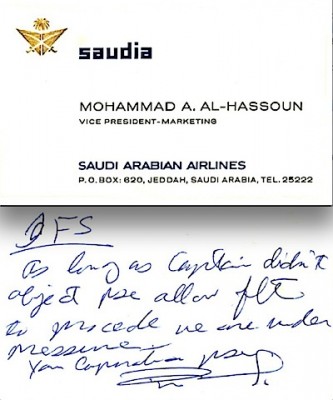

Early in the program I was presented with a challenge when the ground staff attempted to close the door with no empty seats and five passengers standing in the aisles. An agent insisted that we must have had lap babies sitting in seats and urged me to check again. I already had and there was no way to rectify the situation without strapping children into single seats two at a time. When the captain came down to find out why we hadn’t left, the ground agent quickly began arguing with him in Arabic, then stormed off the airplane. Moments later, he returned and handed me a business card from the vice-president of marketing, who apparently had witnessed the chaotic boarding and was now on the ramp. On the back of the card, he wrote:

Early in the program I was presented with a challenge when the ground staff attempted to close the door with no empty seats and five passengers standing in the aisles. An agent insisted that we must have had lap babies sitting in seats and urged me to check again. I already had and there was no way to rectify the situation without strapping children into single seats two at a time. When the captain came down to find out why we hadn’t left, the ground agent quickly began arguing with him in Arabic, then stormed off the airplane. Moments later, he returned and handed me a business card from the vice-president of marketing, who apparently had witnessed the chaotic boarding and was now on the ramp. On the back of the card, he wrote:

“IFS: As long as Captain didn’t object please allow flight to proceed; we are under pressure. Your cooperation please.” Fortunately the captain was standing next to me and I handed him the card. He smiled and walked off the airplane, embraced the VP and exchanged greetings, explaining the situation, then returned with the agent, who glared at me before taking off the five standees, and we left. When I thanked the captain, he simply replied, “Khalas!”

I should insert here my great respect for all the people of MEA, who were trying to run an airline under the most difficult circumstances. Varying religious beliefs were put aside while on duty and long stretches away from home strained everyone’s nerves, something we American IFS types had to keep in mind. There were flights at night between Riyadh and London when we passed over Beirut and were able to see tracers from rocket fire within the besieged city. How these good people kept focused was at times was beyond my comprehension.

In addition, the ground engineers (maintenance personnel) assigned to Riyadh, Cairo and Jeddah met every flight and made repairs, usually at night when the airplanes were on the ground for more than a few minutes. I rode in the cockpit several times and was impressed with the professionalism displayed by the pilots.

The IFS schedule pairings were initially set up by the Saudia manager at London, and involved a good deal of deadheading between London and Riyadh. After two months, we convinced him to let us to set our own rosters, promising to cover all flights including extra sections, which often presented additional flying on short notice. Allan Johnson and I did most of the paperwork and concocted a plan allowing us to eliminate the deadhead flying except in unusual circumstances.

We immediately got rid of the reserve schedule by always being in London and available a day in advance to cover an earlier flight if someone was sick. Knowing that to do so would create a hardship on another IFS, we almost never called off schedule and no one ever flat-out missed a trip. Some of the pairings were rugged, with short layovers in the Kingdom, but we were not considered working crewmembers so had no rest limitations to deal with. And best of all, we could trade trips at will, making it was easy to create some generous stretches of time off.

MEA wasn’t the only airline leasing airplanes to Saudia. This 727-2H3 was operated by Tunis Air, seen at Cairo.

Trip pairings were somewhat challenging because the London–Riyadh service only operated five days a week, while RUH–CAI–JED–CAI–RUH was flown daily. This meant some five-day pairings while others were eight days, with two of the circuitous, two-day Jeddah roundtrips before returning north or one Jeddah visit plus a Riyadh–Beirut (BEY) pairing that gave the 747s brief visits to MEA’s maintenance headquarters. There were trips when we arrived at Riyadh from London with only a few hours at the hotel before proceeding to Jeddah. Then it became a struggle to stay awake that following evening. On several occasions I slept at Jeddah for more than 14 hours nonstop.

Settling into the routine, it felt as though I was meeting myself coming and going at Riyadh, or spending what seemed like forever in the hotel. In addition to the short layovers, we had 30-hour stays as part of the eight-day pairings. With no restaurants in the immediate vicinity of the hotel, little shopping and no sightseeing to speak of you can imagine how challenging it became to occupy one’s time. Much of it was spent writing letters, reading (I averaged more than one book a week) and keeping an audio journal of my adventures. Some of the rooms had black & white televisions featuring a single channel and a once-daily, 30-minute news program in English. Cartoons with Arabic subtitles quickly grew old. Full-length films were shown on the main floor utilizing a Betamax video system that produced a fuzzy picture and frequently broke down.

With two IFSs usually overnighting in Riyadh, we hooked up briefly but one of us was arriving late at night while the other left early the next morning, so we rarely had time for much interface. Men and women on the crew were always assigned rooms on different floors and we were not allowed on floors occupied by the opposite sex (Room visitation Letter). Other than gathering in the lobby or the dining room, there was little opportunity for socializing.

The situation at Jeddah was marginally better. The two Saudia hostesses were at a different hotel, but we often met up and went out for dinner. The IFS was not permitted in the hotel and the hostesses were restricted by curfews. They had to wear pants and dress conservatively in this country where women were not even allowed to drive a car. (Hostess curfew bulletin) After dinner we usually went to the souk, where I cashed my expense checks (often received weeks late) for Saudi Riyals, British Pounds and US dollars. MEA crews flew a three-leg day RUH–CAI–JED–CAI and spend the night in Egypt, then reversed course, thereby avoiding Jeddah overnights.

Dates and nuts were readily available at the souk, as evidenced in this web picture, of good quality and very reasonably priced.

Drug stores allowed the purchase of over-the-counter meds that required prescriptions back home. Among them were antibiotics like Tetracycline and Amoxicillin; various sleep aids and Lomotil, otherwise known as “instant cork,” for diarrhea. The souk was a source for the purchase of food to be eaten in layover hotels. I subsisted during most of my time in the Kingdom on oranges, dates, processed cheese, cashews and pistachio nuts. Although the water was deemed safe for our tender digestive tracts, most of us stuck to the bottled variety.

The crew meals were not all that appetizing within the Middle East, where pigeon was considered a delicacy. About the only time I ate any of the inflight food was out of London. Arabic bread (called Pita bread by the more politically correct) and humus could be relied upon for safe consumption in restaurants. With pork products forbidden, the Saudis consumed large amounts of lamb and other beef products, which I ate until passing by the local open-air butcher facility one day in Riyadh, where swarms of flies caused me to lose my carnivorous appetite.

We constantly flew with different cockpit and cabin crewmembers because of our different schedule patterns. The Saudi pursers were based at Jeddah and often did not show up for flights within the Kingdom, but curiously were there for every Beirut and London trip. They sold duty-free cigarettes, scarfs and fragrances in flight and otherwise assisted with the service.

Beirut Adventure

Gulf-India at Beirut, under tow from MEA’s maintenance facility to the terminal. The mountains of Lebanon and cooler temperatures were a welcome relief from Saudi Arabian weather. ©Jon Proctor

I had transited Beirut in 1975, but never left the airport. My first Saudia visit began on June 28, 1977, on Days 6 and 7 of an eight-day trip. The flight was packed, with every seat taken in addition to 39 lap babies and 24 crew. Adding to the drama was Sheikh Pierre Gemayel, founder and head of the Lebanese Phalangist Party, who rode in the upper deck lounge. Our captain was so concerned about his safety that he ordered the search of everyone who came upstairs, including ground staff before departure. As a result we took a lengthy departure delay. On arrival at BEY, two military tanks pulled right up to the airplane with soldiers manning their gun turrets. Welcome to war-torn Lebanon.

An appreciated relief from Saudi lodging was Beirut’s Coral Beach Hotel on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It featured large rooms with balconies, a swimming pool and the Beachcomber Bar. Getting to the hotel from the airport required passage through numerous security checkpoints staffed by armed militia from the Arab peacekeeping force. By the time I got to my room a splitting headache drove me to take a swallow from the bathroom tap rather than wait for a bottle of water from room service. In retrospect, I should have washed it down with a beer from the mini-bar.

Our return to Riyadh the next day was less dramatic but we nearly didn’t leave at all when our three security guards, Saudia’s version of Sky Marshalls, didn’t show up for the flight. There was quite a flap between the cockpit crew and the ground staff. Our captain did not want to wait for them, but Saudia Operations headquarters in Jeddah told him that without security the flight would be cancelled. Finally it was determined that the guards had been arrested at a checkpoint for “excessive firearms!” MEA personnel intervened and they were quickly released; we left more than two hours late.

I started feeling nauseous about halfway back to Riyadh and was almost too dizzy to walk by the time we reached the Elkherji, suffering massive diarrhea most of the night. Unable to get out of bed in the morning, I called the Saudia rep at the airport and a Lebanese doctor was at my room within an hour. Ascertaining that I drank tap water in Beirut, he smiled and shook his head. “You Americans have very tender intestines,” he remarked. That evening, Bob Van Well arrived on the flight from London and firmly told me that he would work my return flight to London in a few hours and take me with him, adding, “You can be sick in London but not here!”

This is just one example of our group hanging together and taking care of each other, especially within the Kingdom. We relayed messages, picked up passes issued at Jeddah for family members and hauled mail back and forth, to and from London, sometimes taking it home for stateside mailing if one of us was headed in that direction.

Just before departure late that evening, a ground agent came aboard and told me the flight was full and I would have to deplane. Bob quickly consulted with the captain, who mercifully allowed me to ride on the cockpit jumpseat. Shortly after takeoff an MEA steward made up a bed of sorts on the floor behind my jumpseat, with blankets and pillows. I slept there until letdown for London and was driven to Maryfield Orchard to recover, which took a couple of days. Meanwhile, Svein Husevold deadheaded to Riyadh and covered Bob’s pattern. I covered Svein’s trip a few days later and vowed to never again consume tap water, or even ice, in Lebanon, or anywhere in the Middle East for that matter.

Home Visits

Faster than a speeding bullet! BA Concorde G-BOAA at London, shortly before I boarded her for a supersonic flight to Washington DC.

It was more than six weeks before I managed a long enough break to board a TWA flight from London to New York and home. A month later, I splurged and bought a British Airways ticket on Concorde and flew to Washington, D.C., connecting on to Cincinnati and the first Airliners International, a convention of civil aviation enthusiasts. Unlike the 5-digit fares at the end of supersonic service, my ticket cost “only” £433, around $650 in those days. Riding “Speedbird” at Mach 2.02 was truly the trip of a lifetime. For a recap of the flight that appeared in Airliners Magazine, click here.

The tax-free advantages of being based overseas limited returns to the U.S. and early on I decided to forego the benefit and not restrict my stateside visits. I had already traveled extensively throughout Europe and as we refined the schedule, generous blocks of time off presented ample opportunity for frequent extended trips back to Connecticut. There were a few challenges during the 1977 summer season, especially at the height of Freddy Laker’s London–New York standby fares, which forced me to route through Boston twice but with three, and sometimes four daily London-New York flights, I otherwise had little trouble finding an open seat.

Continued Challenges

Golf-Hotel at Cairo, about to operate a teacher flight in the middle of the night.

Early in July we began operating the first of several “teacher flights.” Most schoolteachers in the Kingdom were Egyptian and flown home, with their families, to Cairo from Riyadh for summer holidays. The only large-capacity aircraft available was one of our 747s normally scheduled for an overnight layover. So after a long day and evening, an IFS would be stuck with this unique charter, operating to CAI and ferrying back to RUH; duty periods stretched to 16 hours or more. But we had guaranteed coverage of all 747 flights and it wasn’t a whole lot worse than sitting or sleeping at the Elkherji. In the fall we would ferry to CAI instead and bring full loads back.

Strikes and slowdowns by the London and French air traffic controllers resulted in late-summer delays, some of them substantial. As a result trips between LHR and RUH made stops at JED, only adding to the headaches as we arrived well after schedule. Loads within the Middle East were the heaviest we had seen to date. My logbook says that on two September segments, RUH-CAI-JED, we carried a total of 810 passengers including lap babies.

One of the return teacher charters occurred during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar when Muslims eat only at night and fast during the day. We were about to leave CAI around 3 a.m. when a hydraulic leak was discovered. The ground engineers expected to have it fixed quickly, but the delay continued and with dawn approaching it became apparent that it would not be possible to get airborne and serve the meal before daylight. Someone suggested we keep all the window shades closed but in the end an even longer delay was incurred and we fed our passengers on the ground.

Meeting TWA 707s during our ground stops at Cairo provided a reminder of home and usually U.S. newspapers. 707-331B N8705T is seen arriving with its No. 4 engine thrust reverser stuck in the open position.

A few weeks later I arrived at Riyadh from London three hours late after another Jeddah stop and got to the hotel at 7 a.m., in only an hour before my scheduled departure over to CAI and JED. Someone filled in for me and I deadheaded on a Saudia 737 RUH–JED later that day in order to get back on my pairing. As was the custom, I dutifully reported to the cockpit and introduced myself to the captain. He was in the right seat and a student captain was in the left. I thought little of it until arrival at Jeddah, when we landed, and landed, and landed, three bounces. The first one was hard enough to make me wonder if the landing gear had survived. Long runways and good weather were a saving grace at Middle East airports.

Back in Riyadh, I was assigned to a suite at the Elkherji. A suite? I didn’t even know they had suites. But it had clothes in the closet and food in the fridge. I enquired the next morning and found that a long-term guest normally occupied it but was out of town for a few days. The hotel was oversold and there were no other rooms available.

On a regular flight in August, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and his party of six were booked to fly from Cairo to Riyadh. We had already gone through individual bag identification, where all luggage was lined up on the ramp and passengers had to claim their own before being loaded into the containers. No bags were left unclaimed. Arafat and his group were driven to the foot of the boarding stairs, where our captain met and talked with them in what appeared to be a cordial manner. Then, as quickly as they arrived, the group left and we were given clearance to depart. The captain told me this was not unusual but simply Arafat’s own security measures; he would book on one flight then take another. It was a quiet but unnerving ride over to Riyadh.

Upon landing, the captain paged me to the cockpit to advise that there had been a fire at the Elkherji and all electricity had been turned off. We would be going to the Meridian Hotel instead, where the MEA pilots regularly stayed. That good news proved to be inaccurate. Instead, we wound up in the Sahari Palace at the airport, a property that made the Elkherji look like a five-star hotel. The rooms were small with only a ceiling fan to circulate the otherwise hot and stale air. During my fitful sleep I felt something dance across my face, a rat! The rest of the night was spent with a light on.

Frank Messina arrived from London in the morning. We met in the lobby and I told him which room to stay out of. As we parted, he remarked, “Oh by the way, did you hear? Elvis Presley died yesterday.”

I worked the flight up to LHR that morning. Blessed with a block of 11 days off, I flew on to Chicago and joined brother Bill for three baseball games between the Cubs and Dodgers, then enjoyed some time home in Connecticut.

Posing with pretty MEA hostess Rosy Haladjian at Cairo. Such a friendly picture would not have been a good idea within the Kingdom. ©Jon Proctor

When I returned to the Kingdom, we were back at the Elkherji. But the London air traffic control people staged another slowdown and my first trip to Riyadh was rerouted via Jeddah. I got to the hotel at 5 a.m., just before briefing time for the trip over to CAI and JED. There wasn’t another IFS available so I pressed on. The briefings were held in the hotel, giving me a few more minutes to compose myself. With less than 90 passengers on the CAI segment it was a struggle to keep my eyes open.

In Jeddah I barely stayed awake until early evening, then slept until noon the next day. By then we had a “permanent” room at the Kandara Palace, 311. It was larger with a more reliable air-conditioner and a television set. Broken drapes, peeling wallpaper and being on the noisy side of the hotel were considered acceptable tradeoffs for the upgrades.

As we were about to depart for CAI on the way back to RUH, the ground agent came up the steps with our paperwork, accompanied by two security guards. “This one needs to get off,” said the agent, pointing to the name of a Saudia hostess who was listed as a deadheading crewmember. I had barely noticed her boarding the flight and now couldn’t find this Egyptian girl. She had apparently changed into civilian clothes to blend in with the passengers. An announcement was made asking everyone, including the crew, to produce their passports for inspection. Eventually the hostess was found and taken off the flight in tears. Our Saudi purser told me her exit visa had apparently been cancelled “by a higher authority.” Many scenarios went through my head and that look of fear on her face stayed with me for a long time; I never saw her again.

That evening as we landed at CAI, I noticed much stronger braking on rollout. We suddenly stopped on the runway and were towed into the gate, whereupon the captain came storming down from the cockpit and off the airplane, yelling loudly at the ground agents. We came to learn that he had been told the last 1,000 feet of the runway was unusable, but not that it was became a KLM DC-8-63 had blown tires on landing and stopped at the end of the runway, followed by a full passenger evacuation. People were wandering around next to the airplane and on surrounding taxiways. Fortunately no one was run over.

Other challenges that summer included a woman about to give birth, another suffering an epileptic seizure and a heart attack victim. To my knowledge they all survived and in each case we had one or more doctors aboard.

Fall Changes in the Air

With implementation of the fall 1977 schedules, three of the five weekly LHR–RUH flights included an en route stop at either Geneva (GVA) or Rome (FCO). The time adjustments meant shorter layovers at RUH off the southbound flights and later LHR arrivals northbound; flights between RUH, CAI and JED were not affected. Our passenger load factors dropped significantly, but European ATC delays continued well into winter and the two weekly nonstops to RUH more often than not stopped at JED. Shortly after the new schedules were implemented, FCO airport firemen walked out on strike for a day. We knew in advance and happily operated nonstop LHR-RUH. On another occasion our aircraft, Golf-India, was damaged the previous day at LHR, pushing our departure for RUH back to 3 a.m.

Coming back from RUH to LHR on October 13, we were to operate nonstop until, at the last minute, an operations agent came out to tell us a ground vehicle had damaged an L-1011 at JED and we were to divert there and pick up the passengers. I went to the cockpit and told the captain who smiled and said, “We would be 32,000 pounds overweight for landing at Jeddah. Tell them we can’t do it.” I passed along the information, only to be advised, “Tell the captain to dump fuel on the way.” I was astounded and the captain was angry. But we did just that, jettisoning more than 5,000 gallons of kerosene over the Saudi desert.

On the flight up to London, a deadheading pilot wearing the uniform of cargo carrier TMA of Lebanon introduced himself and asked if I would give him my Saudia uniform wings, explaining he was a memorabilia collector. I told him I could perhaps acquire and mail a set to him, in trade for some airline post cards, which I collected. We exchanged business cards and I thought little odd that none of the MEA crew seemed to know this fellow, unusual for a small airline community in Lebanon. After not receiving anything from him, I didn’t send the wings.

Two weeks later someone from Scotland Yard in the UK summoned me for a brief interview at Heathrow Airport. It seems the alleged pilot had tried illegally to enter Bahrain and was tossed in jail; my card was in his wallet. The TMA identity was a ruse; he was a terrorist of sorts, or so I was told. I heard nothing further about the incident.

The annual hajj pilgrimage to Mecca occurred in November. Our 747s were not pressed into charter service for this purpose, but we had a large group on a CAI–JED segment; they appeared to be upper-income people, all adults. Lots of singing and praying was the order of the day and it was interesting to see happy pilgrims on their once-in-a-lifetime journey.

There were still smoking and no-smoking sections on TWA back in the late 1970s, but not so with Saudia; the whole airplane was one big smoking section, and some of the cigarettes from the Middle East were rather pungent. On a flight from LHR, the ground staff established a no-smoking section for the upper deck. No one on the crew was told and it all went unnoticed until we stopped at FCO and took on more passengers, filling up first class. Smokers were intermixed with no-smokers and we had a tough time separating them.

Southbound flights could also be problematic because passengers often brought their own liquor on board. It wasn’t allowed but when consumed discretely no one was the wiser. Then, of course, there were the few who, realizing they were not going to see another drink for quite a while, overindulged and got drunk. I recall having to deplane two such violators at FCO on separate occasions.

Christmastime in the Kingdom

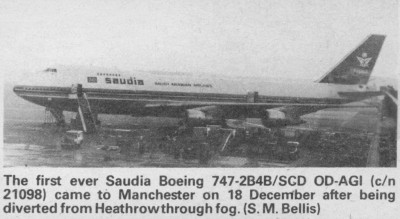

I was scheduled for just two five-day trips in December, both with Rome stops in each direction. Having only three days off in between, I couldn’t head back home until December 26. The first pairing went fine until the last day, when London was socked in with heavy fog. We circled over Dover for nearly an hour, and then diverted to Manchester, England, becoming the first ever Saudia jumbo to land there. The front door was opened an hour later, followed by another 2-1/2 hours before the bags were unloaded. The passengers were transported to London by train while those of us on the crew waited for further instructions.

Finally, after a few more hours, I was instructed to buy train tickets for myself and the two Saudia hostesses and return to Heathrow Airport where we would be released. The three of us took a cab to downtown Manchester and, having received no specifics on what type of accommodations should be purchased, I bought three first-class seats on the express train to Euston Station in London and we hurried aboard what appeared to be less than a first-class train, then waited for departure. While doing so, I glanced out the window and noticed a train on the adjoining track. Directly across was a dining car with white linen and fresh flowers on the tables. At that moment I realized we were on the wrong train, but it was too late, as ours began moving. We had boarded an extra section laid on to accommodate 350 passengers from a diverted South African Airways flight. There were no meals, even for purchase and our car had no heat.

After landing in Manchester at 10:30 a.m., more than 8 hours after departing from Riyadh, we finally arrived back at Heathrow shortly before 7 p.m. I skipped the formalities at our office in the Heathrow Hotel, picked up a rental car and returned to Maryfield Orchard, then slept for 11 hours without rolling over.

Trip 2 was easy by comparison. After arriving at JED on the second day I deadheaded back to CAI and was the guest of MEA Head Steward Atef Ghalayini and his wife, who lived there. Atef and I worked many flights together and when he offered a quick tour of Cairo I readily accepted. We went out on the town for dinner and a floorshow, enjoying the Egyptian nightlife. It was my first time away from the airport. A day later I deadheaded back to Jeddah and resumed my pattern.

Christmas Day was spent back in Riyadh and felt like anything but. That night as I rode out to the airport with the crew, a loud boom box was blasting Arabic music and there were no signs of the holiday. I hoped it would be my last Christmas in the Middle East.

We were right on time getting back to London, giving me the chance to change bags and clothes, then ride British Airways Flight 661 (on a pass) nonstop to Miami with a connecting Southern Airways flight to Orlando for a slightly late Christmas celebration with my brother Dick and family in Winter Park. The BA flight was comfortable, even in Economy, but lasted more than 9 hours. Again, I slept well that night in Florida.

Into the New Year

Allan Johnson took this shot of me about to leave Maryfield Orchard for work in my snappy new uniform.

My first trip of 1978 was not until January 6, giving me time to visit Connecticut on the way back to London, followed by an 8-day trip. By then we had donned new Saudia uniforms that were beautiful, although their French designer probably envisioned much more slender people. Saudia even provided us with two pairs of shoes.

In February a strong letter was issued to us after a newspaper article described “shameful behaviour” of a cabin crew on a flight staffed by a non-London based crew. (Saudia crew behaviour)

Weather in the Middle East had cooled off and was quite pleasant, even in Jeddah, although we knew it would be short-lived. My trips were routine except for a diversion when a sandstorm, with 55-mph winds, arrived at Riyadh shortly before we were due in from Cairo. Our alternate was Dhahran but that airport became saturated with other flights so we instead landed a Bahrain and sat two hours before returning to Riyadh.

Security checks were heightened without explanation in January, resulting in delays of more than two hours while the entire airplane was searched. In March, fighting in Lebanon escalated. I was about to depart for Beirut when the captain urged me to get off the airplane and take the two Saudia hostesses and Saudi purser with me. “We live there. It is not worth the risk for you,” he said. Earlier we learned that TWA’s management employee insurance did not cover disabling injuries resulting from acts of war and at this point the issue was still unresolved. I took the captain’s advice and told the others to get off, but the purser insisted on taking the flight. I did not object. There were repercussions but shortly thereafter our insurance policies were amended, or so we were told.

Our contracts called for 30 vacation days that were not accrued, meaning we had to take them within the first year. Mine began March 27th and I headed home with for a month away from the Middle East. Part of it was spent in Arizona with my brother Bill, watching Spring Training baseball, something we did on an annual basis. It was capped off with 10 days in Connecticut.

Home for Good

The rest of spring and summer became somewhat of a boring ritual, back and forth on the same two jumbos, flying the same patterns over and over. We had been offered a 10% bonus to extend our contracts by a year. It was tempting, but several factors led me to pass up the offer.

A lighter moment, posing with MEA hostess Dalal Sinno at the R-5 door, en route from Riyadh to London on my last Saudia trip.

Two incidents nearly resulted in serious injury to me, or worse. As I was waiting for the paper work in Jeddah one afternoon, with one foot on the steps and one in the cabin of the airplane, a ground agent suddenly backed the loading steps truck away from the aircraft. About to fall 16 feet to the pavement, I grabbed onto the bottom of the doorsill and barely crawled back into the cabin, tearing two fingernails in the process. On another occasion, while retrieving my luggage from one of the two the crew containers parked outside operations at Riyadh, the tug driver pulled away without unfastening the containers; I was in between them and only kept my legs when an MEA pilot grabbed my belt and yanked me away.

Those close calls, coupled with other frustrations and a desire to go home, sealed the deal and I gave notice to leave at the conclusion of my contract on October 30.

By fall I was due another 30 days of vacation and had the month of September off. I vacated Maryfield Orchard August 31 and spent the next four weeks moving back into my Connecticut condo, relaxing and getting ready for a return to civilization.

I came back to London and flew two more trips, completing the final pairing on October 16. The next morning TWA Flight 709 carried me home from this great adventure and on to my next one.

The Saudia contract was probably my greatest test of self-control. In the process, however, I learned a great deal about Middle Eastern culture. While a rewarding and memorable experience, I was most happy to be back in the States for good, especially with the approaching Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. In the end I was the only one to decline the contract extension, although Allan Johnson wasn’t too far behind me. I returned to flight attendant status, resplendent in new attire thanks to a TWA uniform change implemented during my absence. It was good to be home!

A Footnote

Although the Lebanese civil war supposedly ended in 1990, unrest has flared up periodically. Most recently a car bomb was detonated in a residential neighborhood of Beirut. To this day I especially think about those wonderful MEA people – Michele, Atef and the others I worked with – and contemplate how many are still with us.

February 7, 2014 update: Today I received a wonderful surprise, in the form of an e-mail from former MEA hostess Nidia Kiwan, who identified both Rosy Haladjian and Dalal Sinno. She reports that Michel and Hadia Khalifeh are both still with us, but sadly confirms the death, 16 years ago, of Atef Ghalayini. Thank you so much for this information, Nadia.

Thirty-three years later at a 2011 TWA DCS reunion in Denver, six of us from the London domicile gathered for this photograph. Left to right: Svein Husevold, Tom Donahue, Yours Truly, Jerry Warkans, Allan Johnson and Paul McGowan. A toast was also proposed for those we’ve lost: Ray Campbell, Frank Messina and Bob Van Well. ©Jon Proctor

A complete review of the Saudia IFS program is posted on the TWA DCS Alumni Association website at: http://twdcs.org/Saudiahistorypage.html

NEXT: Return to the USA

Great read Jon. And you didn’t do anything to get your head separated from your body! Waiting on the story of your dad.

Thank you John for sharing your experience during your assignment to Saudi Arabia. We would run into you guys occasionally in London and wished we could have been part of the program.

Very interesting

Thanks, Mike; that will be the next chapter I write.

I admire your stamina and ability to work there. Great adventure, Jon.

Jon thank you so much for the excellent detailed accounts. I particulary appreciate the history as I was part of that history having started my airline carreer with TWA at Cairo Late February early March 1977. I worked those 707 and L-1011’s and 747 so many times as airfreight and ramp agent/load planner/ticket agent and FIC (flight information coordinator) all at Cairo, then crew controller ramp supervisor and Flight Dispatch Officer at JFK/JFKWD . Great memories with TWA crews on Cairo layovers. You made me feel and re-live the the history. I too worked for Saudia for 2 years at JFK in between two periods at TWA. Currently as you know I am a flight Dispatcher for United at Chicago. Best regards and thanks again for keeping the history alive JON.

Very sincerely / Vic Grace

Jon,

I thoroughly enjoyed this account of the Middle East offer. (I too was offered the chance and declined). I marvel at how much you remember. Thanks again for the great read.

John,

Fun and memorial experiences! You could have written a book and I would have gladly paid money for it. Well done…keep it up…I look forward to more interesting stories from your career.

Ben

Jon,

Wonderful story, thank you for sharing it with us.

Bill

Jon: I can relate to all of your Saudia stories as little had changed into 2012 when I retired; except that as 747 cockpit crew we had contractual 4-star accommodations at MED/JED/RUH/DMM. . . . However, the multi-national contractor cabin crews were still having to “double-up” and suffer flagrant abuse of duty times. -Hans

Jon……. thanks for the insight of your interesting carreer.

What happend after 1977?

Stay tuned, Jan … it’s coming :o)

I did a spotting trip to England in September 1980 and remember very well those MEA 747’s with Saudia colors. It was fantastic to see them. Great article Jon!!!

I have been enjoying reading the stories of your time with TWA. I’ve been working at American since 2010 and have enjoyed hearing all of the former TWA employee’s stories, but yours seems to come alive more then any i’ve ever heard! Will you be continuing after 1977 soon?

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, working on the next airline career chapter and hope to have it up in the next few weeks.