TWA Trivia

TWA L-1011-500s – Close but no Cigar

One of the launch customers for the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, TWA acquired 38 (although two were sold on delivery to Saudia). The last five were longer-range L-1011-100s. Some of the earlier acquisitions were also converted to that standard for trans-Atlantic flights, but the airline did not take any of the short-body L-1011-500 models that were well-suited for long-haul missions. However, that might have happened if TWA’s financial position was stronger in the early 1980s.

When the decision was made to cease TriStar production at the end of 1981, Lockheed managers authorized construction of five “white tail” L-1011-500s, speculating that customers could be found for the unsold aircraft. Despite aggressive marketing efforts, the TriStar 500s sat more than a year without attracting interested buyers.

During a company road show, TWA CEO Ed Meyer lamented to his employees that Lockheed Chairman Dan Haughton had personally called him to offer the five airplanes at a bargain-basement price, pleading, “Make me an offer.” Meyer told the audience that the company was so strapped for cash that he couldn’t buy them, even though the extra lift would have been welcomed.

Stories abound surrounding earlier negotiations to convert purchase options for the basic model to -500 standards. The above picture, an artist’s concept of the airplane in TWA colors, was one of many produced in various airline liveries for use by Lockheed sales people; note that it shows only three exits, versus four on the standard model, and was 13.5 feet shorter in length. In any event, the TriStar 500 never joined the TWA fleet.

TWA Stripes

Where did the idea for original double red stripes on TWA aircraft come from? Fellow TWAer and historian Milo Raub was told by John Roche that in the 1930s, President Jack Frye was walking down a street in New York City and saw a painting of a TWA airplane in a store window. The artist had added double stripes on the vertical fin. Frye liked the idea, bought the painting and brought it back to TWA’s headquarters at 10 Richards Road in Kansas City (where a TWA museum is now located). He gave the painting to John Roche, who was assigned to the project. Roche transferred the stripes to TWA drawings, and then to the airplanes. After the end of World War II, the double stripes were carried over to the full length of the aircraft fuselage. Below are examples of prewar tail stripes only, and postwar applications. Both pictures are from old TWA archive files.

©Jon Proctor Collection

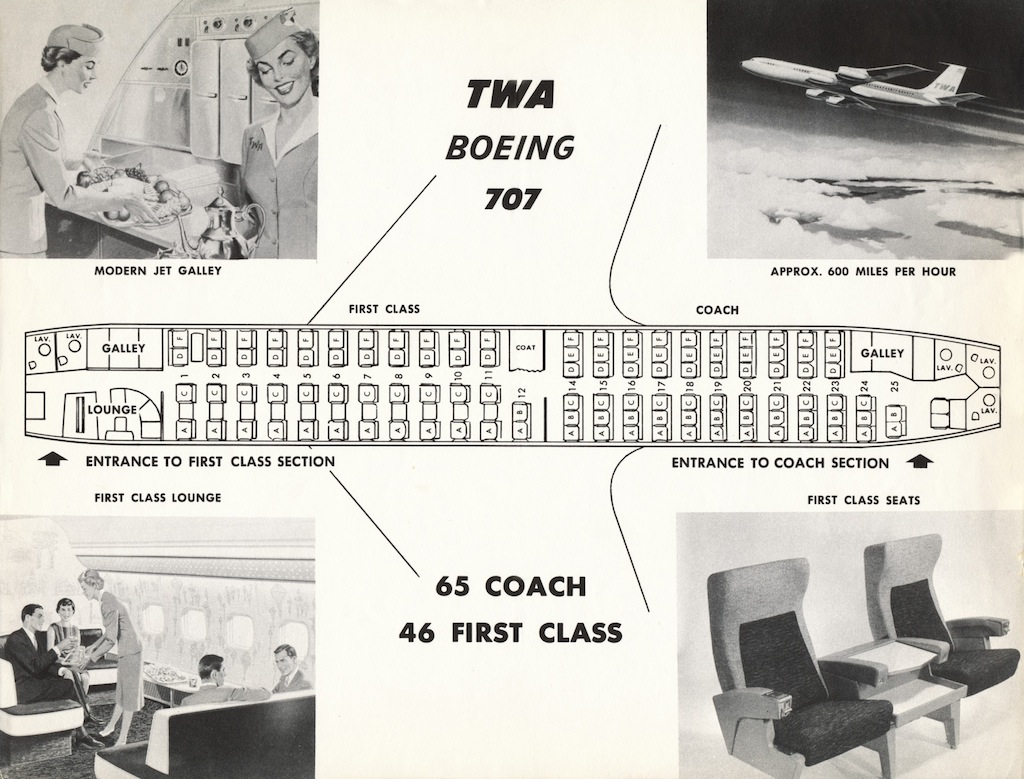

Reflecting the different mix of customers at the time, TWA’s first 707s were configured with no less than 46 first-class seats. This diagram also reveals how the front cabin was originally to feature five-across seating, which was to be an industry-wide policy. By the time it was decided to go with four-across, first-class seats were already being delivered for aircraft installation. To compensate, a table replaced the middle seat, as shown in the picture. Later, new, wider seats were installed.

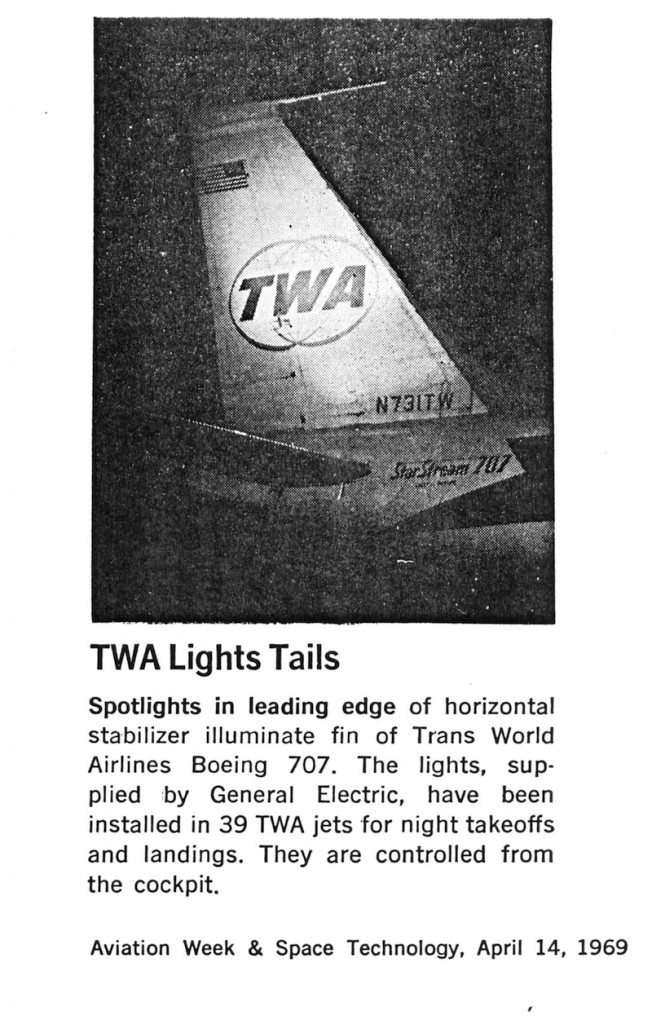

TWA was first to light up its aircraft tails, and allowed other airlines to copy the idea in the name of safety, providing more aircraft exposure at night.

On April 6, 1967, TWA operated its last scheduled Constellation passenger flight and became the first airline to go “all jet,” although 1649A Jetstream freighters soldiered on for another month, until May 11.