TWA – Trans World Airlines

After returning to college for the spring semester in 1964, I worked part-time at Biltmore Travel, located in the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. The facility was nothing more than a window in the lobby but a contractual agreement with the hotel required that it be open seven days a week. Owner Bill Williams and his wife, Alma, took weekends off and I filled in. On Saturday nights, I slept on a cot in a second-floor office. Unlike my La Jolla Travel adventures, it was not an especially fun experience. Customers were few and far between and it quickly became a boring couple of days. I only lasted a month or so.

The search for a real airline job continued. Naturally, American Airlines was my first choice, and Dad arranged for an interview with Elmo Coon, who was in a high-management position with AA in San Francisco. They were not hiring at the time, but I was assured that something surely would open up soon. An application with Continental nearly resulted in a ticket agent job, until the recruiter took a second look at my application and realized that I was wearing contact lenses, which disqualified me for a front-line position. I never understood that policy.

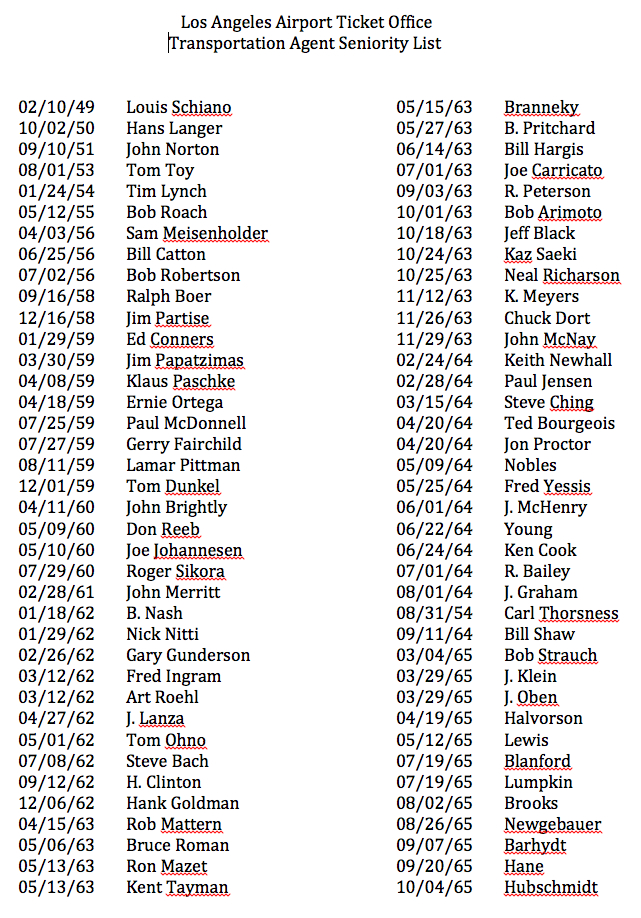

Back in La Jolla on a weekend visit, I lamented with Joe Ginder about my desire to get on with a “big airline.” Joe told me to look up Dick Tewell, TWA’s Airport Ticket Office (ATO) manager at LAX. I did, and Dick was cordial but told me that all hiring came from the employment office at the hangar; he wasn’t in charge of recruiting. Undaunted, I went over to Employment, and was greeted in a somewhat perfunctory manner by one Dorothy Schumann. Yes, she said, they “occasionally” hired transportation agents [a name later changed to customer service agent, or CSA], and I could fill out an application. I came to learn that “TAs” usually came from the ranks of ramp servicemen, in the form of promotions, or from transfers, but that was not mentioned. I dutifully completed the job application form and took some comprehension tests, then left after being told that someone would call if they decided to consider me.

Less than a week later, I got a call from “Dot,” as I would come to know her by. Our telephone exchange was more cordial. Could I come in for an interview with Mr. Tewell? Yes, I could, and would. The second visit was friendly. Dick smiled as I entered his office, and remarked, “Now you know why I had to refer you to Employment!” In short order, he offered me a job, to begin on April 20, adding that they had not hired anyone off the street as a TA in quite awhile; apparently my timing was very lucky. I was about to go “Nationwide, Worldwide” with TWA, as the slogan read.

I reported to work as directed and met another new hire named Ted Bourgeois, also beginning his first day with TWA. Canadian by birth, Ted had earlier worked for Air France and was fluent in French. Our first duty day was consumed with paperwork, uniform fittings and initial training. Almost immediately, I learned about seniority, and the fact that Ted and I didn’t have any!

At the time, the senior ticket agent was a fellow named Louie Schiano with a 1949 date of hire. There were a few others in that rarefied air of tenure, like Tom Toy, who were able to work the early day shift on the ticket counter with Sunday and Monday off, considered the most desired of all schedules. Ted and I were slotted into “swing shift” on the counter, 3:30-to-midnight, checking bags and little else. As non-contract (non-union) employees, we didn’t punch a time clock; the Lead Agent Bud Hall kept track of overtime.

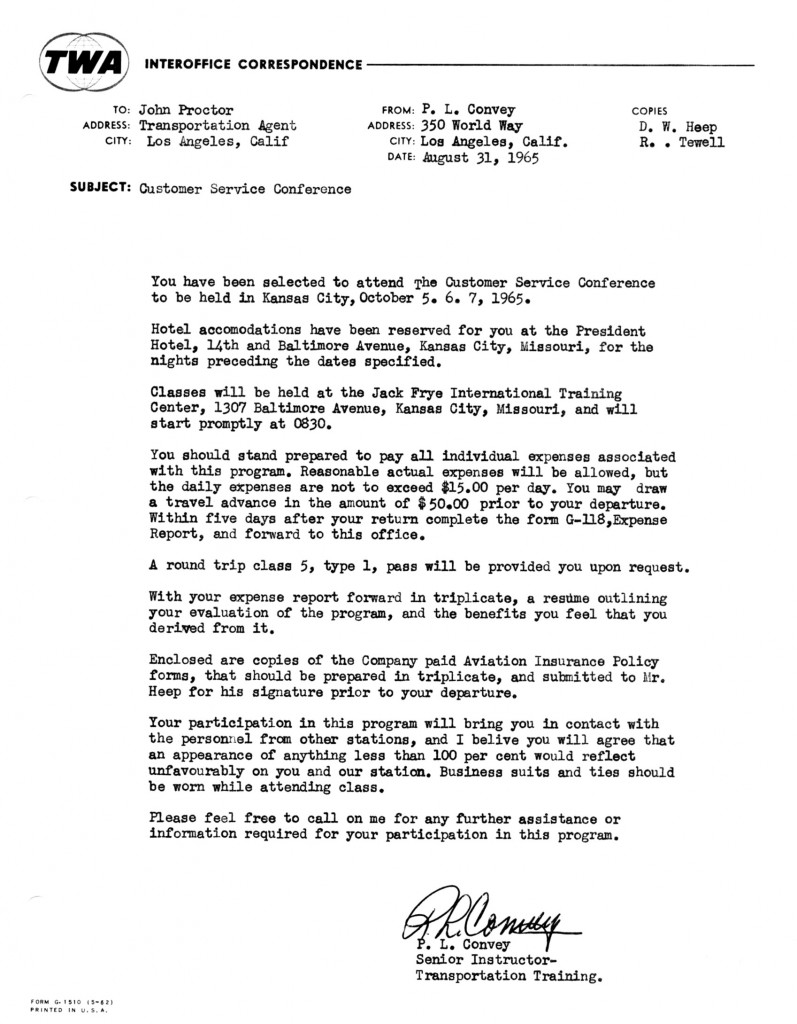

Not long after I started with TWA, my sister-in-law, Ann Proctor, left TWA to start a family. Brother Bill worked her last trip, Flight 19 from Washington DC to LAX and I met the flight. One of my fellow workers snapped this picture to mark the occasion.

Funds were deducted from my paycheck for several months to pay for my uniform, which fit like a glove thanks to the tailor who had an office in the base of the Theme Building, adjacent to an employee cafeteria. Initially I wore my own dark slacks and an oversize, hand-me-down blue uniform jacket, replete with TWA’s globe logo above the breast pocket. I can still remember looking at myself in the reflection of the terminal front glass as I stood behind the ticket counter, admiring that logo and realizing that I was really a full-time employee, earning the sum of $415 a month, a nice raise after topping out at $330 a month with PSA.

Although Ted and I had basic ticketing knowledge, we were still slotted into classes with regional instructor Gene Baca, in a classroom above the ticket counter. Gene was great guy, who made ticketing entertaining. He used a blackboard with cities circled, marked and connected, his hands flying back and forth as he constructed sample fares. I remember Gene referring to Albuquerque as “Apple Creek,” Phoenix was “Fee-HO-nix,” and Las Vegas, of course, was “Lost Wages!”

Within six months, I had risen to $467 monthly, thanks to a merit increase and a “GSA,” or general salary advance. The latter was routine among salaried workers to keep up with union wages and discourage organizing in our ranks, or as TWA put it, “to maintain our position equal to or better than the Industry.”

It’s hard to believe that, in 1964, there were no female transportation agents; only men. One exception was Gloria Bechtol, who came in late at night and did the ticket stock reconciliation. She spent her time in a room behind the ticket counter; a sign on the door said something like, “Electrical Control Room,” to dissuade any prospective thieves from disturbing her or the money she counted and readied for deposit.

This picture from the TWA Skyliner employee newspaper shows the LAX ticket counter as it looked when I began with the airline.

At the time, LAX was the biggest ticket office on TWA’s system in terms of revenue; a lot of it was in cash. One night, we were robbed; as I recall, it was an inside job pulled off by a former employee who left Lead Agent Sam Meisenholder tied up. The burgler was later caught and prosecuted.

We did have ground hostesses, who greeted customers from in front of the counter but they were not allowed to handle bags. They also met passengers arriving on connecting carriers such as Pacific, United Continental, Delta, National Pan Am and overseas carriers. At the time, Bonanza Air Lines was using Gate 37 in our satellite; ground hostesses even met those flights if onward TWA passengers were expected.

Working the counter was only one step above the information counter, a circular affair between the street and tunnel to the gates. From “bag check,” one graduated to “future ticketing,” a portion of the counter with seats, where passengers and agents planned itineraries and wrote tickets, sort of like a travel agency; it was later renamed “Tour Planning.” The hotbed of activity was “immediate ticketing,” where customers actually purchased tickets on the day of departure. Finally, working “gates” in the satellite building rounded out my on-the-job training. It was generally the most preferred assignment, although we did have some ‘professional counter’ people that just liked the steady, predictable pace downstairs at the street level counter.

Among the advantages of working gates was the fact that you didn’t need to take out your change fund and ticket validator plate. No ticket writing was done in the gate satellite area. Working on the counter meant the daily ritual of “check-out” in the back room, reconciling your ticket receipts with funds collected, for which we were allowed 15 minutes at the end of the shift.

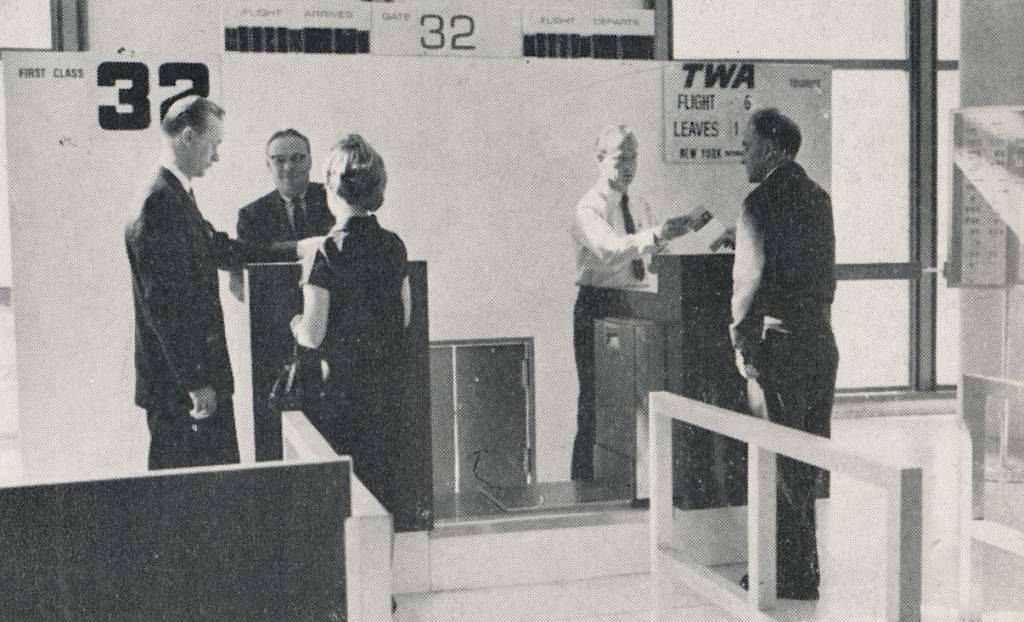

Another Skyliner image reflects a posed photo at Gate 32. Second from the left is John Kuzma, who was so kind to me back in 1959.

There was nothing said as long as you tallied, or at least came close, but I did have the distinction of joining the “Hundred-dollar club” on two occasions, meaning I was short more than $100. The Los Angeles-St. Louis fare was something like $101 and change. I was off that exact amount both times, indicating that I had almost certainly issued free tickets on that segment. Station Supervisor Dick Veres gave me a lecture the first time, to the effect that my enthusiasm was exceeded only by my lack of attention to detail, but at the same time he winked and told me it wasn’t the end of the world. Paul Convey, our senior training instructor, gave me a bit stronger advice after the second infraction. He only knew of a few double members of the Hundred-dollar club, and none who had accomplished the feat three times and remained gainfully employed at TWA; that got my attention.

I was just getting into the swing of it, so to speak, on the counter before being moved out to the gates to learn the ropes in the fast lane: Jetway driving, passenger check-in and boarding and having a little bit of freedom from being chained to a spot on the counter. My excitement quickly died when Bud Hall told me why I was elevated to the gates so quickly: “You’re the junior guy and it’s time to do your penance on mids.”

Published by the Skyliner during initial Jetway training in 1962, the picture shows several people I would work with at LAX. Ted Lindsey and Ralph Baer stand on the left, with Dick Tewell in the center. To the right of teletype operator Pam Cavilli are Gene Vargo and Bill O’Connell. Click on image to enlarge.

Going Nocturnal

Luck often has a way of going your way, but not every time. Why was I going to mids – the midnight shift – while my associate Ted Bourgeois was not? His last name started with B; mine begins with P. In the case of a tie in seniority, first in the alphabet wins; I lost!

At this point in time, I withdrew from college and moved to El Segundo, literally across the street from LAX. My parents were disappointed, but Dad wrote a philosophical letter, urging me to make TWA the best airline in the world. Many years later, I learned that he had only completed two years of college. Perhaps Dad kept that from me with hopes of my not following in his footsteps. Nevertheless, he and Mom were fully supportive once the decision had been made.

In retrospect, night duty was not bad at all. We only had three midnight agents, (although another worked in Lost & Found until 3:30 a.m.). The other two, who worked it by choice, would become my longtime friends: Gary Keller and Jeff Black. Like me, they were footloose and fancy-free bachelors, young and enjoying the Southern California beach lifestyle. I remember when I was still on swing shift and working on the ticket counter, Jeff was driven to work, delivered right in front of the building by a gorgeous young lady driving an MG; it would be the perfect scene today for a “LAX at Night” TV series.

On mids, you either worked from 11:30 p.m. to 8 a.m. on the counter or Midnight to 8:30 a.m. on the gates, and we switched around. Two of us had regular nights off and the third (I can’t remember who) rotated his schedule. One night a week, we had three guys, or perhaps the odd one worked a different shift; again, my memory fails me.

Likewise, we had the same lead agent five days a week; it was Doug Swope when I started, with Bill Hilton as the relief man on the other two nights. During my tour on mids, at least four or five leads did their time in the nocturnal barrel. The reason I went through so many of them is that nobody was being hired off the street as a TA; all were arriving via promotion or transfer and with more seniority than me. As a result, I spent the better part of 1964 learning how to survive like a bat.

Although my sleep cycle never did adjust, I liked mids; it was usually pretty quiet yet we had enough work to keep busy. There were a few late-evening departures to deal with. Flight 85 to San Francisco, 84 to Kansas City and 72 to St Louis; all left after midnight; 84 and 85 were Convair 880s. Flight 72 operated with a 707, as did Flight 58, the last Las Vegas departure on any airline out of LAX, at five minutes past midnight. Continuing on to Chicago, New York and Hartford, it occasionally served as a back-up for passengers missing any of the “red-eye” flights earlier in the evening.

One regular Flight 72 passenger I got to know pretty well. Dan McIntyre, a TWA commissary supervisor in St Louis, commuted weekly between there and his home in L.A. More on “Mac” follows … much more.

After the midnight rush hour, it was quiet until Flights 3 and 15 arrived from New York, 10 minutes apart at 2:25 and 2:35 a.m.; both were 707-131Bs. Flight 3 came via St Louis, while 15 stopped at Chicago-O’Hare and continued to San Francisco at 3:20 a.m.

On weeknights, Flight 15 offered coach service only; first class was bulk-loaded with mail. The seats were fitted with protective covers and sacks were strapped into the seats and shoved underneath. Instead of a commissary truck, a belt loader was positioned at the forward galley door for mail unloading; some of it rode through to San Francisco. I remember a few times when we shifted the remaining sacks around to make room for non-revs, although that was rare; the flight almost never carried heavy loads LAX-SFO.

Steve Allen and his wife, Jayne Meadows, arrived from the East Coast nearly every Thursday night, one each on Flights 3 and 15. Allen was then host of The Tonight Show, then televised from New York City. To obtain a three-day weekend, the Friday show was taped on Thursday in time for them to leave JFK at 10:50 and 11 p.m. respectively. I was told the pair didn’t like to fly together “because of the kids,” (I’m not sure they even had any), but they drove the L.A. freeways in the same car; go figure. On a few occasions, when one of the flights was running late, we would open up the Ambassador Club so Steve or Jayne could snooze while awaiting the other flight. Both were delightful people who didn’t ask for any favors and always appreciated the extra service. The same was true of Jayne’s sister, Audrey, who flew on TWA with husband Bob Six on occasion; more on that later.

One of the many television shows filmed in part on our property included this take with Gary Moore being greeted by a hostess at Gate 39, sans Jetway, on April 8, 1966. ©Jon Proctor

Movie filming took place in our terminal on a fairly regular basis, thanks to our Special Services department that handled the industry, Byron Schmidt and Al Douglas, compromised a staff of two. Much of the on-site work was done at night in order to cause the least disruption. A project that continued for about a week was filming of the popular TV series “Mission Impossible,” for an episode that I was told wound up on the cutting room floor. The plot called for a casket to ride our luggage conveyor belt from the satellite building to the baggage claim area. En route, a member of the MI crew was to replace the corpse and disappear into the night. In real life, we never put caskets on the bag belt!

It appears this movie clip was shot at the LAX ticket counter, probably part of the same story line as the picture I took of Gary Moore.

Although Hollywood types didn’t normally ride on the “red eyes,” I remember Danny Kaye departing on “the big Duce,” Flight 2 LAX-JFK, which departed at 10:45 p.m. Another time, when Frank Sinatra rode on it, Commissary was advised to board an extra supply of Jack Daniels. After flying in on his Lear Jet from Palm Springs, Frank made a dramatic appearance just before departure time, looking very good with a deep tan and waving to everyone who recognized him.

Jayne Mansfield created quite a stir on August 30, 1964, when she departed on Flight 72 to St. Louis, traveling in front while her baby and nanny rode in the back. Shortly before departure, Jayne leaned out of the forward galley door and waved to the ground crew while letting it all hang out. Operations below completely stopped for several minutes, and I’m not sure how they coded that delay.

On October 12, Ray Charles came in on Flight 15 and I walked him down to the front of the building; we didn’t have any Skycaps on duty at that hour. After retrieving his luggage, he said, “I need to drain my lizard, Pal,” so we stopped at the men’s room. Ray was impressed that I knew about the Martinliner he used to own. We had a few laughs reminiscing before I put him into a cab.

In contrast to some of the flashier celebrities, I recall walking to the arrival gate to meet Flight 15 one night and seeing Julie Andrews sitting in a chair by one of the adjacent gates, quietly reading a book while waiting for a friend to arrive from New York. What a contrast to those who demanded all sorts of perks. Shelly Winters was notorious for waiting to board a flight until the rear Jetway had been pulled so she could embark through the front entrance, giving the appearance of traveling in first class; she routinely flew in coach, unless one of the Passenger Relations Reps upgraded her, something she always asked for.

In the Still of the Night

After the last late-evening departure, the counter agent restocked bag tags and other supplies, and checked in those few passengers going to SFO on Flight 15. He otherwise kept busy writing tickets for the morning shift immediate ticketing customers. It was great practice and interesting. Although fares were much simpler then, there wasn’t much in the way of automation; it was almost always done by hand. Reservations sent a list via Teletype, with passenger itineraries; only the international records contained prices; we had to calculate the rest. Without a multitude of fares in those days, our pricing nearly always matched that of the reservations quote, so passengers were not surprised when paying for their tickets at the airport.

The most demeaning job on midnight counter duty was to maintain the dreaded fare tariffs, ticketing manuals and the infamous MP&P; Management Policy and Procedures manual. Revisions came in droves and presented a most boring exercise. One thing that stands out in my mind was the reference, across the bottom of each MP&P manual page, which read something like “Nothing in this manual supersedes good judgment on the firing line.” It was that little disclaimer that authorized employees to do the right thing, so long as they could justify it.

Air Fare Simplicity and Integrity

While we’re on the subject of policy, another one of that era that has stuck in my mind all these years was the ticketing “Golden Rule:” Always give the passenger the best (cheapest) fare. There were tricks, like “hidden city” fares, when a lower price was offered to a city beyond the passenger’s destination. We showed calculations in a fare matrix on the ticket, with the hidden city circled. Agents exchanged information like this as they discovered fare combinations.

There were a few regular passengers who knew the tricks as well. One I remember traveled out on Flight 74, the red-eye Boston nonstop flight. His company required that he fly down to Washington, D.C. from Boston, then back later in the week, on Flight 19, the westbound dinner flight. His company allowed first-class travel on night flights, but only coach on other segments. He would come up to the ticket counter and ask if Flight 74 was full. When it wasn’t, which was most of the time, he would downgrade and sleep across three seats. At the same time, he re-booked in first class on Flight 19 back to LAX, taking advantage of our Royal Ambassador Service, which back then offered a choice of six entrees and all the trimmings.

These changes resulted in the refund of a few dollars, which would be issued in the form of a Miscellaneous Charge Order (MCO), sort of like a credit slip. On those nights when Flight 74 was heavily booked, the customer would stay up front on that segment, upgrade to first class on Flight 19 and pay for the difference using MCOs he had accumulated during his travels.

It should be remembered that, in those simpler days, the difference between first class and coach was minimal, $15.80 between LAX and JFK, for example. One regular customer used to joke that he could “spill that much” when riding in front with free booze. This partly explains why our domestic 707s had 34 first class seats, plus four more in the lounge if needed.

Another rule we lived by stated that there was nothing good about an empty seat when an airplane departed. Whenever possible, we moved passengers up to earlier flights, especially if they had connections to make down the line. At its peak, TWA had 10 flights daily from LAX to New York/Newark, hourly during the day, so it was not uncommon to check in a customer more than an hour ahead of his or her scheduled flight; most were delighted to leave an hour earlier.

Company in the Night

While working the counter on mids, I had company from 4 a.m., when the Bonanza Air Lines ticket counter, which was actually an extension of ours, opened for business. Joe Curtain would come on duty, a paper coffee cup in hand, with eyes barely opened. His shift had to be even worse than straight mids, but Joe was usually awake and functioning within a few minutes of his start time.

The TWA and Bonanza ATO managers at LAX had an unwritten rule about hiring away from each other, but Joe became an exception, having interviewed first with TWA. With no openings available, he went to Bonanza but later was hired by Dick Tewell and joined us. We became great friends, in large part due to our simultaneous night tours of duty and the fact that we were both big L.A. Dodgers fans. Joe transferred to Boston in the 1980s and, sadly, succumbed to lung cancer in the late 1980s; he was a great guy.

Meanwhile, Upstairs …

This picture is a bit out of sequence, timewise, taken in 1968. That’s me with Joe Curtain, modeling new uniforms. From our unlikely introduction to each other in the wee small hours of the morning, we became best friends for 25 years; I sill miss him.

Out in the satellite gate area, we would restock the podiums with ticket envelopes, claim checks for last-minute bags and set up seat charts for the first flight of the morning. Pegboards were used, with seat numbers on small tags, which we affixed to the boards. During gate check-in, coach passengers could select their seat choices from the board, at which time the agent would pull the tags and staple them to the appropriate ticket jacket. (First-class passengers were offered seat assignments when booking their reservations.) Although a far cry from today’s automated procedures, the system effectively prevented duplicate seat assignments. This service was only offered at flight origin. Passengers boarding at intermediate points had to grab empty seats as best they could.

A rather menial task was completed downstairs in “Doc,” or Documentation, where an agent normally reconciled tickets, passenger counts and the like; the desk was not staffed at night. It was the midnight gate agent’s responsibility to make up first-class name cards for the morning Royal Ambassador departures. Adorned with the R/A crest, each card, affixed to the seat back with a pin, added a little elegance to these premium-service flights and made remembering passenger names easier for our “hostesses,” a job title TWA pioneered in the 1930s. At the time, all were female while all pursers on international flights were men.

The midnight gate agent also extended all the Jetways for cleaning, then ran them back to the parked position. Another task was to pull Jetways from planes headed to the hangar, and push them up to returning aircraft. It was a bit of a ballet at night; full-time taxi crews from maintenance positioned the morning departures at each gate. A few aircraft would inevitably come into the correct location on late-evening flights and not need attention at the hangar, so could be left at the same gate.

TWA maintained a locally recorded phone message, giving the status of arrivals and departures, which was updated periodically by the public address girl (always a woman back then), but on mids, we didn’t have anyone assigned to the task, so it was left to someone in FIC (flight information control) in Ops, or designated to someone else. I got a kick out of making the recording and listening to myself. There wasn’t much to tell on mids, and it usually boiled down to stating that all flights were operating on time.

Further entertainment could be had by listening in on the PLF, a kind of party-line phone that connected all the domestic stations and departments. To use it, you simply picked up the phone and inquired, “Line Clear?” If it was in use, “Negative” was the response. At night, usage was light, often taken up by the maintenance departments. Occasionally someone would listen in and when it was asked if the line was clear, replied, “Affirmative!”

Load control agents worked in FIC, tasked with weight and balance for each flight, recording cargo, mail and passenger weights and completing a “weight slip,” which was taken to the gate buy the TA and then tallied with the control agent just before departure. One of the early morning load agents was Dale Povenmire, who somehow got nicknamed, “Piffelheimer!” Dale was an old-timer by my standards, having begun his career at Mansfield, Ohio. When that station was closed, he transferred to Topeka and worked there until it too was closed, then came to LAX. We joked that he might be a jinx, leaving all these closed stations. “That’s why I came to LAX,” remarked Dale; “What are the chances of this station being closed?”

Dale’s favorite stunt, once settled at his desk, was to get on the “bitch box,” an intercom between FIC and the maintenance shack, and begin loudly whistling “Reveille” to wake up his pals, who often did not particularly appreciate the gesture.

As more people began their day shifts, the station began coming to life and the pace picked up. The mids gate agent normally worked one of the early departures before ending his own work period.

A Classic Mistake

Credit it to working on the back side of the clock. Let me set the stage. Flight 32, the 8 a.m. 707 departure to Las Vegas, Albuquerque, Kansas City, Chicago and New York, was routinely assigned to Gate 34. Sometime during the summer schedule, we picked up an additional JFK nonstop, Flight 10, also departing at 8 a.m. It was assigned to Gate 32 at the beginning. On this fateful day, I was assigned to work Flight 10. Unlike Flight 32, it carried light loads and was preferred duty for the yawning midnight agent.

All went smoothly. I was just about ready to close the Jetway door and kick out the flight when two men came running from the escalators, shouting, “Wait for us; wait for us!” Normally, I’d get a call from the ticket counter to warn me of any late customers, but none had been received. Never mind, I grabbed their tickets; first class! The commissary top-off man was standing by and I told him to add two meals for our “go-shows,” passengers who were not shown on the passenger list. As we ran down the Jetway together, I accepted copious words of appreciation from the two men, slammed the door and pulled back the Jetway, a minute or two late.

As was always the custom in such situations I gave the captain a football-like “time out” hand signal, which in this case meant, “Please give me on-time, Sir!” He smiled back and nodded, indicating that he would report the flight as having departed on schedule.

Seen that same summer, Flight 10 taxies out for takeoff. On the fateful morning I worked that New York departure, it carried two unsuspecting passengers who thought they were going to Las Vegas! ©Jon Proctor

With little else on my mind other than heading for home, I took the stack of tickets downstairs, along with the duplicate weight slip and passenger list, counting the tickets and matching names with the manifest. As I penciled in the names of our two “go-shows,” my heart came up through my throat: both tickets read “Los Angeles-Las Vegas.” I had put these two unsuspecting souls on the wrong flight! Running into the adjacent operations office, I told the FIC (Flight Information Coordinator) of my error, and he immediately called the LAX control tower to request that the flight be directed to return to the gate. I still remember the FIC’s response on the phone: “Oh, it has? Thanks.” He looked at me and said, “Well, the good news is you won’t get a delay on this flight; the bad news is that it has already taken off.”

My faux pas was not the first of its kind, but created quite a stir around the ATO for a day or two. I had to write a letter of contrition, which went all the way up to Don Heep, our station manager. Nothing more was said, however; I guess my superiors figured that I had inflicted enough self-discipline. As far as I know, the letter did not even go into my employee file.

Thank you again, Dodo!

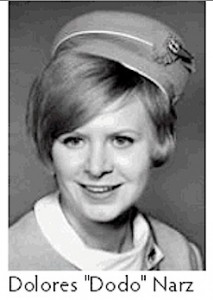

About a week later, one of the passengers looked me up as he was departing on another flight. “Thanks for a couple of the greatest flights we ever had,” he exclaimed. “That Dodo girl got us so drunk, I don’t even remember changing planes in New York!” The aforementioned hostess was Delores “Dodo” Narz, who really knew how to take care of her customers. She turned their misfortune into quite a party.

Alerted at JFK, a PRR had ensured that the two passengers made their “direct” connection to Flight 57, nonstop JFK-LAS, arriving at the original destination about 12 hours after departing from LAX. I asked the passenger when he figured out that he was on the wrong flight. His answer: “Well, we didn’t pay any attention to the announcements on board. It struck me that the breakfast service was pretty fancy for an hour-long flight, but when the movie came on, I knew we weren’t stopping in Vegas!”

I might add that, from the next day forward, Flight 32 was switched to Gate 32 and Flight 10 moved over to Gate 34. I guess that validated the fact that people do associate similar numbers. Fortunately, the affected passengers had a sense of humor, and I had the good fortune of putting them on a flight with a legend; thank you, Dodo!

End of the West Coast Connies

The last LAX Connie flights disappeared that summer. One is shown at Gate 38, with a Convair 880 in the background on the left, and a Bonanza F-27 in Gate 37. © Jon Proctor

I enjoyed two distinct benefits while working mids: all the overtime I wanted and working the last scheduled Constellation flight into and out of LAX.

A 1049G “Super-G, Golden Banner Coach,” Flight 503, trundled in from New York, Cleveland and Kansas City at 5 a.m., and departed for San Francisco at 5:45. With favorable wind conditions, it could come calling as much as 30-45 minutes ahead of schedule. I would just meet the flight to let to L.A.-bound passengers disembark, then lock the Jetway door and came back to board the handful of local customers; sometimes we had no one getting on at LAX.

This flight, and eastbound Flight 502, departing at 6:55 p.m., were the last TWA Connies flying west of Albuquerque, and were removed from the schedule that summer. I don’t recall the exact date, but I do remember making the final boarding announcement at the gate podium and realizing that nobody was hearing it. With our daylight outbound flight not departing for another two hours, the terminal was deserted, and Flight 503 pulled out of Gate 31 without fanfare.

I also got a chance to work the Polar flight a few times. TWA began flying nonstop from California to Europe in 1958 with Lockheed 1649A “Jetstream” Starliners, something that had always fascinated me. Imagine a flight with an 18-hour duration.

During the summer of 1964 as a 707, Flight 860 operated a San Francisco-L.A.-Paris Orly once weekly and, I think, twice weekly LAX-SFO-ORY. Coming off the midnight shift, I was often held over for four or six hours of O.T., and remember the first time I got to “assist” on 860. I especially recall the ancient cabin crew that boarded; NY-based and all in their 60s; even the senior LAX hostesses weren’t that “elderly!” There was a certain adrenalin rush watching the airplane take off. Fully laden with fuel for a 10-hour, 50-minute flight, it could be seen eating up every foot of the runway, and then clawing for altitude as it cleared the sand dunes on the western edge of the airport. I’m sure it was an even bigger thrill for the pilots!

Hazardous Duty – Lost & Found

My liberation from mids occurred on October 20, 1964, when I joyfully returned to swing shift with mid-week days off. It wasn’t long before I drew another less-than-desirable assignment: working Lost & Found, in a small office next to the baggage claim area. This was a place where one rarely encountered a satisfied customer. On the contrary, they were usually hopping mad.

As shown in this Skyliner photo, the LAX baggage claim area was spacious. It was also devoid of claim check verification. Bag switches resulted in visits to the adjacent Lost & Found office.

Compounding the pain was working a 7 p.m.–3:30 a.m. schedule, which usually meant a boring time period between midnight and the end of the shift, which coincided with the arrivals of Flight 3 and 15. If they were on time and presented no lost bag challenges, one could leave a few minutes early, but that was rare as the last flights of the evening often brought with them passengers who had mis-connected somewhere back east and became separated from their luggage. Much of the dead time was filled by chatting with the Lost & Found agents at Chicago and New York on our second company phone system, called DITAN.

I wasn’t there to witness it, but one night a disgruntled passenger came into Lost & Found with an axe and chopped the agent desk in half; now that’s what we called a dissatisfied customer! Tim Lynch and Gordon Briers were both on duty at the time, and their story is legendary.

There were a few fun moments here and there, like the time comedian Jonathan Winters came into the office, looking for a pair of reading glasses he had left at an Ambassador Club back east. Chill Wills also visited once when I was working. And although I didn’t meet him, baseball great Ralph Kiner’s bag turned up on the baggage carousel one night and I was able to route it to the owner, who by then was at home in San Diego.

My most unique experience in L&F occurred one night when a middle-aged man and a most attractive, much-younger woman came into the office after waiting to collect a bag off a flight from Chicago. The man had checked in several hours before his scheduled flight and instructed the check-in agent back east to be sure the bag was dispatched on the same airplane he was going to ride. In those days, the procedure for handling such situations was to write the flight number on the baggage check and then underline the number several times, so the boys in the bag room knew not to put it on an earlier flight. This was, of course, long before the stringent security rules we all endure today, and more times than not, the bag was sent out on the first flight to that destination.

When luggage was not claimed within 30 minutes of its appearance on the baggage carousel, it was removed and placed in a locked storage room for security. I escorted my customer to the room, just in case his bag had come in earlier, but alas, it hadn’t. However, there sat on the carousel an identical suitcase, leading us to suspect a bag switch caused by a customer who accidentally grabbed the wrong bag when it closely resembled his or hers. LAX baggage claim featured wide entrances and exits, and we did not require passengers to present their claim checks when leaving. The man was upset, having recently endured similar bag switch.

I asked if the lady had luggage as well, and he replied that she had met him at the airport and was not flying that night. “We’re on our way up to the mountains,” he remarked with a twinkle in his eye.

I noticed a TWA Ambassador club luggage tag on the bag without a partner, and brought it into the office, asking the couple to have a seat while I looked up a phone number and called the bag’s owner. Perhaps he was home by then and could quickly return the bag. The man in the office exclaimed, “We’re in a hurry! Tell him I’ll bring this bag to his house and pick mine up.” If we could connect by phone, it appeared all would work out and both customers would be satisfied. Ah, if life were only that easy.

Just as I reached for the phone, it rang. Behold: it was the bag switch passenger. After profusely apologizing, he explained that he saw the mistake when noticing a different name tag. To make amends, he called the number on the tag. I can still remember the words: “I talked to his wife and she’s coming over to pick up the bag. Can you hold mine until tomorrow morning?” Uh oh … .

I cannot print the expletives that spewed from that man in front of me upon learning the disposition of his bag. His cover was blown, along with what was to be a cozy weekend with a young lady no more than half his age. The couple was last seen exiting baggage claim; loud words were being exchanged.

My First Pass

Los Angeles International as seen from my Delta 880 flight to Florida, on February 13, 1965. ©Jon Proctor

Unlike today, new-hire TWA employees had to wait a full year before qualifying for pass travel, although we were granted 50% reduce rate tickets after six months. I actually got my first pass a bit earlier because of my “juniority,” which resulted in a February 1965 vacation and qualified me for one pass; I would get another five after passing my one-year anniversary. With great excitement and anticipation, I applied for an interline pass on Delta Air Lines between Los Angeles and Orlando, and planned a visit to my brother Dick and his family in nearby Winter Park, Florida.

An old friend, this ex-American Airlines DC-6 carried Sam and me from West Palm Beach to West End, on Grand Bahama Island, where we explored for a couple of hours before proceeding to Nassau. ©Jon Proctor

On February 13, Delta’s Flight 988, a “Golden Crown” Convair 880, transported me to the Orlando airport that was actually part of McCoy Air Force Base, with an intermediate stop at Dallas Love Field. Unlike TWA, which by then assessed a first-class surcharge for non-revs, Delta put all the free riders up front with no additional charge, and I enjoyed a “Royal Service” breakfast and lunch en route.

After a few days with brother Dick, his wife Lucy, daughter Penny and son Rick, I flew down to West Palm Beach on an Eastern Electra from Herndon Airport, the close-in field of choice, for a visit with my friend Sam Givens, who was staying with his Aunt Bess and Uncle Russ Dougherty in Palm Beach. From there we flew to Nassau on Mackey Airlines for two nights, enjoying balmy weather and more than enough rum and tonics. I came back up to McCoy on an Eastern 720, and only too soon back to L.A.

My First Boodoggle

Not all that long after I returned from Florida, the word went around that Delta Air Lines was offering a an interline tour of Jamaica. Called familiarization or “fam” trips in airline lingo, this one was the first I can remember that was open to ATO people, rather than just reservations and sales personnel. For the token price of $39 – yes, THIRTY-NINE DOLLARS – the five-day trip included roundtrip first-class passage, hotel rooms, meals and local tours.

This opportunity was available for the first 20 people to get their checks in. Within a few days, three of us from the TWA LAX ATO received confirmations: Steve Ching, John Brightly and me. We departed on Wednesday evening, May 5, for Kingston via Dallas and New Orleans, arriving there early the next morning. After a few hours of sleep, a bus picked up the group for a tour of the city, followed by dinner and dancing at the hotel.

Our group posed for this picture before departure from LAX. Left to right: Stan MacLean, Delta sales and tour director; Bob Brown, Bonanza LAX; Rose Nicolazzo, TWA Disneyland ticket office; Steve Ching, TWA LAX; Esther Wheeler, Bonanza Ontario; Charlotte Davidson, TWA; Matt Hietala, United LAX; John Brightly, TWA LAX; Betty Ricks, United LAX; Alex Morrow, United Bakersfield; Jim Fogarty, United station manger Bakersfield; Shirley Forbes, Continental LAX; Paul Harvey, United Santa Barbara; Betty Growdon, Continental LAX; Dave Rasmussen, United LAX; Ed Bloom, United LAX; Bob Newman, United LAX; Jon Proctor, TWA LAX; Brenda Thomas, Western LAX; Pat Smith, Western LAX.

We rode a train to Montego Bay on Friday, arriving, as the brochure stated, “in time for cocktails and lunch.” In fact, the cocktails never stopped flowing, with more variations of rum drinks than one could imagine. I should add that kids jumped on the train at various intervals with pails of ice-cold Red Stripe Beer! Everyone hit the pool at the hotel, then it was more dinner and dancing.

By Saturday, I’m not sure anyone had slept for more than a few hours. We were taken on a morning tour out to Ocho Rios and Montego Bay, followed by a gala floor show during …. dinner and dancing.

Our return DC-8 flight Sunday made only one stop, at New Orleans. I vaguely remember some of us dancing in the first-class lounge while the more sensible slept for the entire flight. Steve and I both had to work twilight shift that same day, starting only a few hours after our arrival at LAX. When loads were light and staffing was adequate, we occasionally were allowed to go home early. I still recall my plea to the lead agent, Erv Voight: If you ever allow me to leave early, please make it tonight! He did, and I think Steve got an early pass as well; we certainly weren’t worth much after that long day.

Customer Service Conference

By fall 1965, I actually had gained a bit of seniority, with around 20 TAs coming on board below me. About all it got me was Friday-Saturday off on swing; I was still unable to hold day shift.

My first real boondoggle on company time occurred in October 1965, when I was sent to Kansas City for what one might call “charm school;” charm the customer, that is. While the more senior TAs were being sent on overseas familiarization trips, I was scheduled to attend three days of customer service training at TWA’s Jack Frye Training Center in downtown Kansas City. I was more excited about the plane rides than anything else. With limited trip passes, another flight was a treat. In this case, it was my first chance to ride on a Boeing 727.

A group of agents from all over the domestic system endured this indoctrination to what really constitutes good customer service. M. Wayne Swope was our instructor, a gentleman if there ever was one. For us, it was classroom work by day, play by night. Our $15 daily meal allowance was like a king’s ransom. We ate steak every night, at the Hereford House, the Golden Ox and other top-quality restaurants.

A fellow attendee was fellow TA Bob Trotter from Chicago-O’Hare. Little did we know at the time that our paths would cross many times. The first occurrence was less than a year later and off the TWA route map, in Florida.