Heath Proctor • Pioneer Aviator

(Updated December 29, 2014)

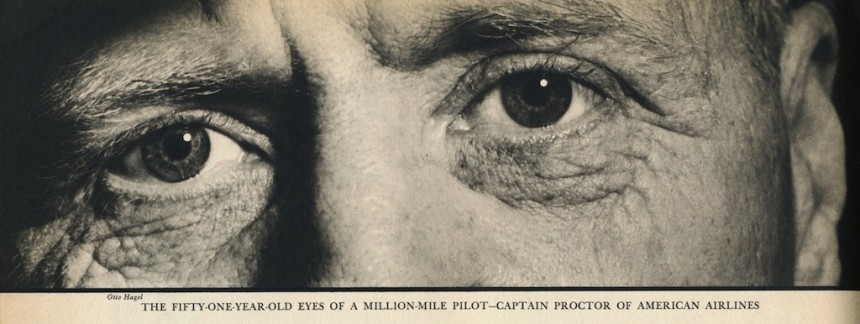

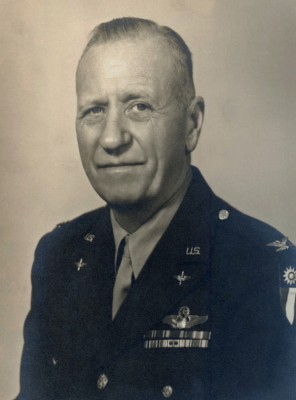

My father, Willis Heath Proctor, flew as a commercial airline pilot for American Airlines and its predecessors for 22-1/2 years. Many pilots have equaled or surpassed that feat, but what made this pilot and his years of service unique probably can best be laid to the time in aviation history when he completed his career: 1927 to 1950.

From October 1917, when he enlisted as a flying cadet in the Aeronautical Division of the Army Signal Corps, until his May 1950 retirement from active piloting, Dad flew an estimated 3,200,000 miles, consisting of more than 16,000 hours in the air, and he did so without receiving so much as a scratch. When signing off his logbook for the last time, he became the first active commercial airline pilot to attain a U.S. airline industry’s mandatory retirement age of 60 (It did not become federal law for another 10 years).

I’ve wanted to write this story for many years. In addition to the text and pictures you are about to read and see, there are numerous links to newspaper and magazine articles, plus historical records about my dad.

Be sure to click on individual images for enlarged viewing.

* * * * * *

Heath, as he was called, made his first complaint on May 10, 1890, in Roscoe, Illinois and grew up on the family’s 500-acre Willowdale Farm, along the Kishwaukee River near Fairdale, Illinois, a small, unincorporated town close to the city of Rockford. His mother, Alice Lorraine Heath Proctor, had returned there from Germany so that Willis could be born in the United States. Her husband, Charles Willis Proctor, remained overseas, completing advanced study as a peripatetic science professor. Upon his return to Illinois, the family moved to Maryland, Missouri and finally to Buffalo, New York. Both parents studied at the Kirksville College of Osteopathy in Missouri, and became osteopathic physicians. ‘Dr. Alice’ performed a variety of medical services, including delivering babies.

Like his father, Dad attended Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania but left after two years and hired on as a lumberjack at Childwood, in the Adirondack mountain range, earning around $60 a month. Perhaps his first sign of restlessness came a year later when he and a buddy were lured north to Canada by the call of the wild, with word of plentiful jobs and cheap land. They bought one-way tickets and hopped a train to Alberta, where farm hands were said to be much in demand.

For a year, Dad worked in Edmonton. It wasn’t long before the sight of trappers trading their furs, along with the stories they told, lured him into new desires. In early 1914, he signed a contract to run a trading post at Fort Norman, on the Mackenzie River, far up in the Northwest Territories of Canada, for the Northwest Trading Company. Click here to read a story about his migration up the Bear River to that location.

During the next three years he worked the post, 1,400 miles from the nearest railroad, receiving supplies but once a year, and rarely seeing another white man. Known to the Indians as ‘enagocah,’ or ‘eyebrows,’ he became friends with many who patronized the post, even “letting them have a little debt” when an expedition proved fruitless.

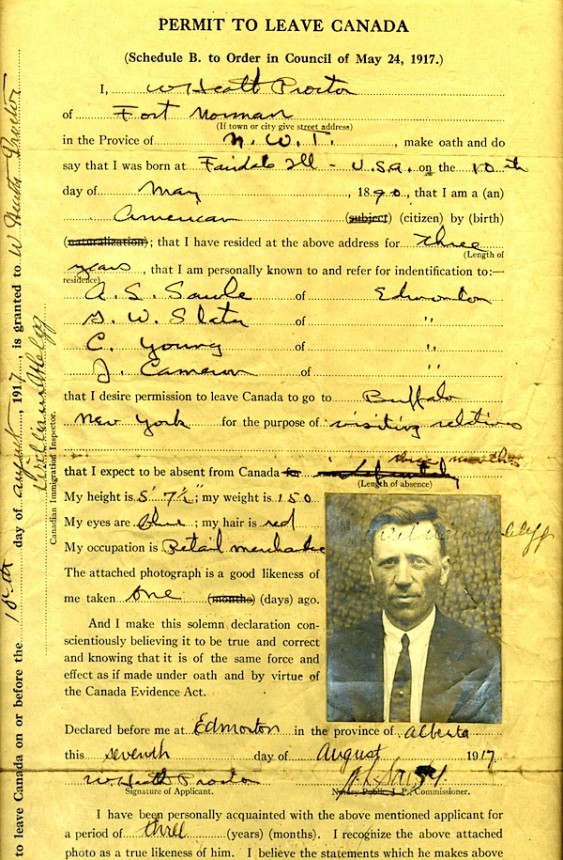

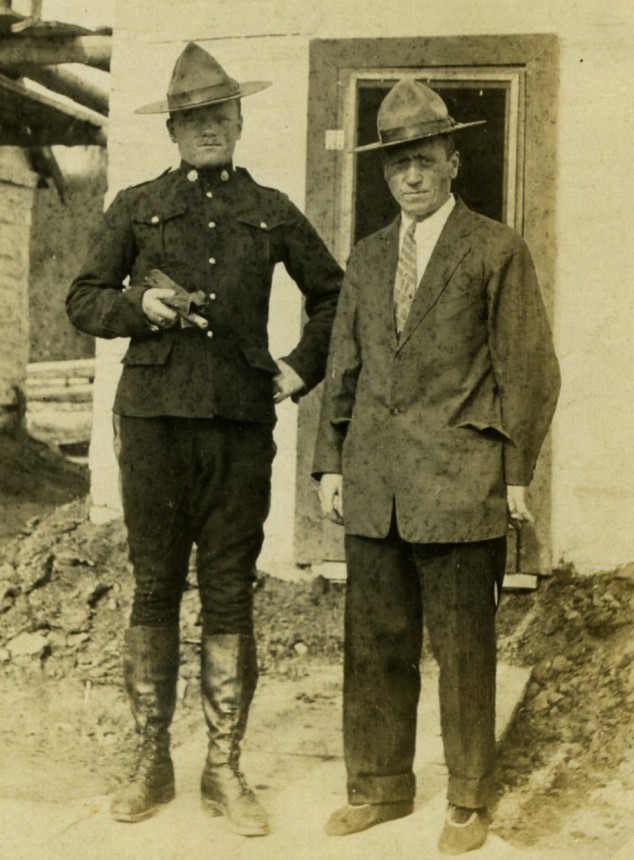

In August 1917 Dad decided to return to his homeland in order to find out more about the “Great War” (World War I), which he did not hear of until several months after it began. In order to cross the border into the United States, he completed the required ‘Permit to leave Canada’ at Edmonton, stating his intention to visit relatives. Arriving back at Buffalo in October, he signed up with the Army Signal Corps, “principally to stay out of the trenches and mud,” he acknowledged. “I had no love for flying at the time. I didn’t know what made airplanes go; it wasn’t romance, for sure.”

In August 1917 Dad decided to return to his homeland in order to find out more about the “Great War” (World War I), which he did not hear of until several months after it began. In order to cross the border into the United States, he completed the required ‘Permit to leave Canada’ at Edmonton, stating his intention to visit relatives. Arriving back at Buffalo in October, he signed up with the Army Signal Corps, “principally to stay out of the trenches and mud,” he acknowledged. “I had no love for flying at the time. I didn’t know what made airplanes go; it wasn’t romance, for sure.”

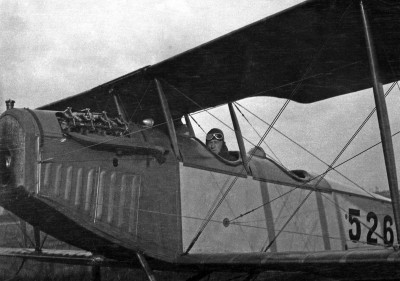

Following ground school at Cornell University, Dad was transferred to Ellington Field at Houston, Texas, for flight training utilizing the Curtiss Jenny. It was during that training when he saw his first airplane accident. “When they pulled that poor guy out,” he recalled, “there wasn’t much left of him. I decided right then and there that I might not get to be the best pilot in the world, but I’d try to be the oldest.”

Dad received his commission and flying wings on May 9, 1918, and joined a provisional wing on Long Island. While waiting to ship overseas he trained other young pilots at Mineola, New York. But the war came to an end in November 1918, and Lt. Proctor never made it to the European front.

After mustering out of the service in March 1919 (still at Mineola), Heath Proctor accepted a reserve commission that summer as 1st Lieutenant in the newly formed Officer’s Reserve Corps, which allowed him to fly for nothing and have a little fun. Two-week, active duty assignments also brought the benefit of more advanced flight training. He married Eva Charles that year, wearing his military uniform for the nuptials. Their son, Richard (Dick) arrived in 1921.

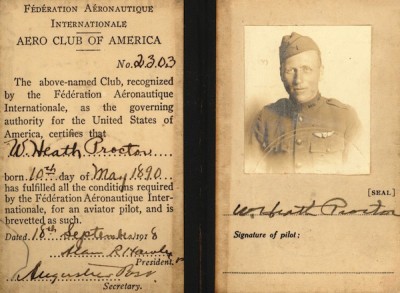

A ‘aviator pilot’ license was issued to Dad by the Aero Club of America, while he was on active duty in World War I. The licenses were not generally required by law and not all pilots applied for them. Searching the Web, I found No. 1702, issued to Jimmy Doolittle three months earlier. ©Jon Proctor

Dad went back to running a trading post for a while, this time in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It was short-lived however, when the Hudson’s Bay Company bought out his firm in 1920, and he again began looking for another job.

There was much talk about a land boom in Florida and Dad migrated south, settling in Coconut Grove and opening a hardware store in 1921. Subsequently, he entered the real estate business (in 1924) and did quite well while retaining the hardware business (until 1927). He even became Municipal Court Judge Proctor for a period of time, beating out an opponent who “was less popular than I,” as he put it. Meanwhile, Dad retained his reserve military status.

Looking rather dapper in Miami circa 1923, Heath tried his hand as a judge, hardware store owner and real estate salesman. ©Jon Proctor

After his marriage did not work out, Heath returned to Buffalo in the summer of 1927, mainly to visit his parents and his gravely ill sister, who died of scarlet fever later that year. It was a difficult time for him, and even more so for his parents; as doctors they stood helplessly by while their daughter slipped away.

While in Buffalo, Dad heard that Major General John F. O’Ryan, then a civilian lawyer, was seeking financial backing to start an airline he was forming as part of Colonial Air Transport. A route between Cleveland and Albany had been successfully bid for, and any speculators with cash on the barrelhead were encouraged to “toss some of it in the till.”

At a luncheon, O’Ryan made it clear that he didn’t know how to fly or run an airline, nor did he know if anyone would use it, but Colonial Western Airways, as it was to be called, had an air mail route, CAM-20, and a boss; any investors would be welcomed. O’Ryan also admitted he didn’t expect to turn a profit during the first five years. Dad decided not to put any money into the venture (“I didn’t think they could last beyond spring,” he commented), but did take a job flying an open-cockpit Pitcairn for $50 a week, a generous salary back in the day.

Later, Dad told me that he would have been wise to do some speculating; when Colonial Western merged into American Airways, he could have purchased shares for $400 that later would eventually have been worth around $100,000. But, as he said, “When you sometimes waited as long as three months to collect a paycheck, you just didn’t see a reason to invest in the company’s stock.”

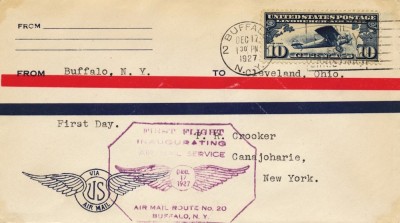

On December 17, 1927, Colonial Western was ready to fly the first airmail flight over Colonial Western’s new route, inaugurating the eastbound service from Cleveland to Buffalo with a Fairchild FC-2 ‘cabin plane.’ Piloted by Raymond Henries, it landed in 2 feet of snow, knocking off the landing gear struts and wheels. [Pilot Henries was killed less than a month later when the new Fairchild FC-2 he was delivering to Colonial Western went down in bad weather between Albany and Buffalo; for more details, click here.]

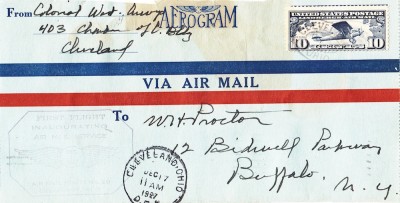

A philatelist himself, Dad gave pilot Henries this letter to carry on the eastbound inaugural flight. ©Jon Proctor

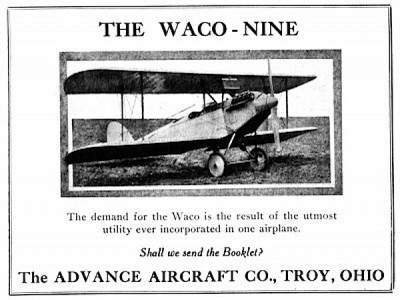

That and bad weather had delayed the westbound flight until December 19, when Heath departed in a borrowed Waco 9, arriving over Cleveland after dark, against all regulations, and landed without the benefit of runway lights, then returned to Buffalo the next day.

On December 29, Dad completed the first roundtrip on the route, with an FC-2. Until then, one-way flights were as much as man or machine could be expected to endure.

By year’s end, Colonial Western had gross income of $365.40 for flying a total of 3,052 miles and carrying 329 pounds of U.S. mail.

Although postmarked December 17, 1927 by the post office, the first-flight covers did not actually depart from Buffalo until the 19th . The 10-cent rate per half ounce was reduced to 5 cents in August 1928. As a result, airmail loads increased 86% for Colonial Western and Colonial Air Transport. ©Jon Proctor

The rate for a letter was 10 cents for a half-ounce ‘Aerogram,” affixed with a ‘Lindbergh Air Mail’ ten-cent stamp showing the famed Sprit of St. Louis, which seven months earlier had completed the first nonstop trans-Atlantic flight, flown by Charles A. Lindbergh. The ‘Lone Eagle’ began his crossing at Roosevelt Field in Mineola, New York, the very airport where Dad had trained pilots 9 years earlier.

Dad told me of meeting Lindbergh at Buffalo when the now-famous pilot landed there during a 48-state tour with the Spirit. This would have been on July 29, 1927, probably around the time Dad began with Colonial Western. His seniority date was in December but that was based on his first revenue flight. There was probably some camaraderie between the two as Lindy had earlier been an airmail pilot himself. Details on his nationwide tour can be found on the web at: http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/gugtour.asp

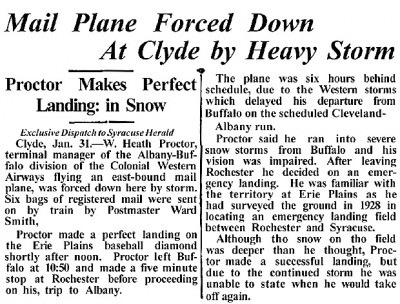

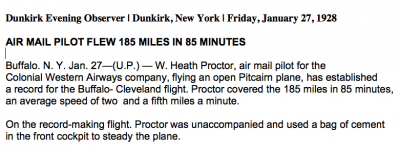

On January 28, 1928, Dad established a new speed record on the Buffalo–Cleveland segment, completing the distance in 85 minutes with a Pitcairn. On June 1 that same year, he flew the eastbound inaugural Buffalo–Albany flight, utilizing an FC-2. Newspaper clippings hailed pilot Proctor’s “several months” experience as an airmail pilot, calling him “one of the Colonial veterans.”

In those days, successful flying was very much a matter of compromise with the weather. While operating a charter flight in April in an FC-2, Dad set the airplane down on property owned by John M Weaver, in North Utica – en route from Buffalo to Schenectady – owing to a sudden spring snowstorm and little or no visibility at the destination city. The three passengers and their pilot spent the night, probably with the Weaver family, and continued the next morning.

The airline gradually added new routes and airplanes. On September 15, 1928, Canadian Colonial Airways, a subsidiary of Colonial Western, inaugurated service from Newark to Montreal, via Albany and Schenectady. Dad completed survey work on the new route, flying a Pitcairn. He had been named Colonial Western’s chief pilot and operations manager in early September, succeeding Edwin Ronne who was killed in an airplane crash in eastern Pennsylvania a month earlier.

During 1928, Colonial Western carried 243 passengers and 45,309 pounds of mail

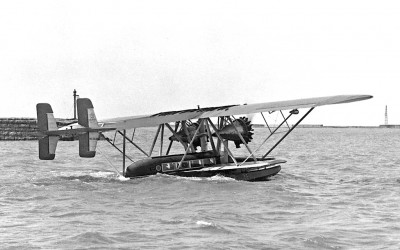

On July 15, 1929, Heath, by now the divisional superintendent for Colonial Western, accompanied the first airmail flight from Buffalo to Toronto, although he did not fly the trip; a Sikorsky S-38 amphibian was used. The one-way fare for the 45-minute flight was $17.50; $30 roundtrip; operated by the Canadian Colonial Airways subsidiary.

That’s Dad, top left and next to pilot Jack Little, accepting the first Canadian air mail for the inaugural S-38 flight from Buffalo to Toronto on July 15, 1929. ©Jon Proctor

By the start of 1930, most of Dad’s flying was in FC-2 cabin planes and the improved Pitcairn PA-6 Super Mailwing aircraft, mainly carrying the mail back and forth between Buffalo, Albany and Cleveland. In January, his employer, along with several other small airlines, officially became divisions of AVCO (Aviation Corporation of America) through a stock transfer, and folded into American Airways, which became today’s American Airlines in 1934.

In Buffalo Dad was introduced to Lucena Wood, daughter of his parents’ close friends. In an August 1930 letter to her, he wrote in part:

I had a tailwind on the way back from Albany last Friday, and I did circle your house once, and milled around for a minute or two, but I can’t stall around very much or someone always gets an idea that I’m lost and begins telephoning the airport to tell them of the terrible plight of the poor lost aviator who can’t find the airport in the dark, and is circling their house. There weren’t any blinking lights coming from your house, so I continued on my way.

The relationship flourished. They married a year later and honeymooned in Havana, Cuba.

1930 was the year that saw the birth of ALPA – the Air Line Pilots Association. The organization’s first official meeting occurred a year later although it would be another eight years before its first negotiated agreement, with American Airlines, was signed. Dad was an ALPA founder and supporter throughout his pilot career, even running for president of the union in 1948; he lost to incumbent Dave Behncke.

1930 was the year that saw the birth of ALPA – the Air Line Pilots Association. The organization’s first official meeting occurred a year later although it would be another eight years before its first negotiated agreement, with American Airlines, was signed. Dad was an ALPA founder and supporter throughout his pilot career, even running for president of the union in 1948; he lost to incumbent Dave Behncke.

After flying Fairchild FC-2 cabin planes between Buffalo and Toronto from mid-March, Dad and his new bride moved to East Orange, New Jersey in June. That month he began flying then-new Ford Tri-Motors between Newark and Boston, a leisurely 1-hour, 45-minute trip that often exceeded 2 hours. Among the Fords Dad piloted was NC9683, which was later restored and now resides at the National Air & Space Museum in Washington, DC.

In May 1932, Dad transferred to Cincinnati and became division superintendent, a job he didn’t much fancy. Pilot Proctor returned to full-time flying in short order, flying from Lunken Airport to Chicago with nine-passenger Fairchild Pilgrims, and later with a mix of Ford Tri-Motors and Stinson U tri-motors. Click here for some history on Lunken, then Cincinnati’s commercial field.

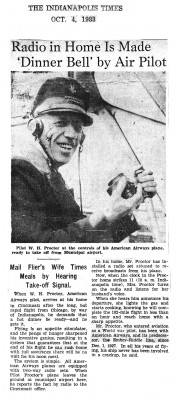

T he Indianapolis Times published an article in October 1933, describing how Heath set up a ‘radio set’ in his Cincinnati home, allowing Lucena to plan for her husband’s arrival upon hearing him report his departure from Indianapolis, en route from Chicago. The story claimed that American Airways Pilot Proctor “demands that a hot dinner be ready upon his return from flight – and he gets it.” The tale went on to say that Mrs. Proctor, when she heard him announce his departure, would light the gas and start cooking, “knowing he will complete the 102-mile flight in less than an hour and reach home with a sharp appetite.” Their first son, William (Bill), was nearly 2 years old. Robert (Bob) would follow a year later.

he Indianapolis Times published an article in October 1933, describing how Heath set up a ‘radio set’ in his Cincinnati home, allowing Lucena to plan for her husband’s arrival upon hearing him report his departure from Indianapolis, en route from Chicago. The story claimed that American Airways Pilot Proctor “demands that a hot dinner be ready upon his return from flight – and he gets it.” The tale went on to say that Mrs. Proctor, when she heard him announce his departure, would light the gas and start cooking, “knowing he will complete the 102-mile flight in less than an hour and reach home with a sharp appetite.” Their first son, William (Bill), was nearly 2 years old. Robert (Bob) would follow a year later.

The Vultee V-1A at Indianapolis, one of Dad’s stops with this airplane. It was fast, with retractable landing gear. ©Indiana Historical Society

Faster Vultee V-1As were gradually introduced on the route in the fall of 1934, alternating with Ford Tri-Motors. Heath got a little variation in the schedule with some added flying between Cincinnati and Washington DC. Indianapolis stops were added to the Chicago route around the same time.

An American Airlines photo of the Curtiss Condor, not one of Dad’s favorite airplanes.

In March, he recorded two ‘practice flights’ out of Cincinnati on Curtiss Condor NC12377, when the type was added to the Chicago schedule in place of Fords. It was the first airplane American operated with sleeping berths. In an interview, when asked about the Condor, Dad replied, “That airplane couldn’t carry any ice at all. It was a big biplane with crossed wires and those things would load up with ice.” That October Dad began regularly flying the DC-2 although he never received any formal training. Again looking at his logbooks, we learn he ‘practiced’ with another veteran pilot, Ernie Cutrell, while riding co-pilot, from Buffalo to Newark, then to Chicago where two local flights finished his familiarization with the new Douglas twin. After returning to Cincinnati, Heath flew his first regular DC-2 trip on October 31, to Chicago, and officially transferred there the following day.

An interesting American Airlines picture showing a DC-2 and Ford Tri-Motor at Chicago. NC14274 was featured in the Shirley Temple film, Bright Eyes. Before Dad had a chance to fly it, the Douglas crashed en route from Memphis to Little Rock, on January 14, 1936.

From then on Heath was on the DC-2s, flying to Cincinnati, Washington DC and Newark, although a Stinson or Vultee was occasionally substituted; the last Ford Tri-Motors had been retired by year’s end.

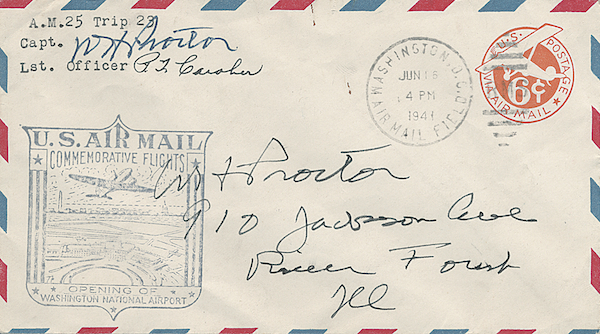

An avid amateur photographer, Captain Proctor took quite a few pictures from the air, but none as significant as the image he captured of the Mason-Dixon Line in 1936.

Surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon began work on the line in 1767, to settle a long-standing dispute between the William Penn and Lord Baltimore families over the boundaries of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Square monuments, 5 feet high and 1 foot in width, were set up every mile along the line.

It is said that during the survey Mason and Dixon had to give their friendly Indian bodyguards three drinks of liquor daily – to keep them friendly.

Dad’s aerial photo of the Mason-Dixon line. According to American Airlines public relations, it appeared in more than 1,800 newspapers and magazines. ©Jon Proctor

A history and geography buff, Heath suspected that what appeared as a firebreak through a forest area near Cumberland, Maryland, was actually part of the original line. He submitted a picture to LIFE Magazine as part of a contest, and won. A U.S. government geological survey later verified the sighting. A September 10, 1937 AP story appears at right.

Pilot Proctor always kept his camera handy. Click here for a story about his Super Ikonta B Speed Graphic.

After flying a regular DC-2 multi-stop trip to Newark on January 21, 1937, Dad spent 2 hours and 15 minutes completing multiple takeoffs and landings in a newly delivered DC-3. The familiarization work continued the next day with Chicago Chief Pilot Walt Braznell, followed by Dad’s regular DC-2 trip back to Midway Airport the same day, via Camden (NJ), Washington DC, Columbus and Indianapolis, accruing 6 hours, 12 minutes in the air.

Heath flew a February 25 DC-3 familiarization trip Chicago–Detroit–Buffalo–Newark–Buffalo–Detroit–Chicago, no doubt swapping takeoffs and landings with other pilots during the long day; no flight times were recorded. Several more practice flights were undertaken in March, interspersed with his regular DC-2 schedule. Dad flew inaugural DC-3 ‘American President’ Flight 20 on April 1, from Chicago nonstop to Washington DC, listed as a ‘Flagship Club Plane’ in the timetable. Although he occasionally flew DC-2 trips a while longer, his regular schedule was the Chicago–Washington DC route on DC-3s, later extended to Newark. On April 13, carrying only 7 passengers, he set a new speed record – 2 hours, 51 minutes – on the same Flight 20, averaging better than 240 mph; scheduled time was 3 hours, 25 minutes.

Looking very much like a DC-3, this is actually a DC-2, distinguishable by its passenger windows rounded at the corners. It’s from my collection, taken late in the type’s AA days, at Little Rock. ©Jon Proctor

On September 21, 1938, a powerful hurricane struck Long Island and southern New England, with destructive coastal flooding and hundreds of deaths. A week later, Dad began flying multiple DC-3 trips for seven days, between Newark and Boston in support of relief efforts. Several flights stopped at Providence. His logbooks show nearly full passenger loads on all segments. For more about the hurricane, see: http://www.weather.gov/okx/1938HurricaneHome

Occasional active duty in the Army reserves broke up some of the repetitive routes flown, and winter months caused diversions and cancellations, but it appears Dad seldom incurred mechanical problems with the trusty DC-3. In September 1939, he checked out Floyd Bennett Field as an alternate landing field. Until now, New York City flights were served through Newark. But on December 2, the new La Guardia Airport* opened for business and on that day Dad flew one of the first trips to land there, from Chicago via Cincinnati, Washington, Camden and Newark, arriving at midnight. He also checked the ‘new’ Philadelphia Municipal Airport in May 1940. A month later, it replaced service to nearby Camden, right across the Delaware River in New Jersey.

* Is it La Guardia or LaGuardia Airport? Most modern-day references use LaGuardia, but the field was named after New York Mayor Fiorello H La Guardia, who championed development of a real New York City commercial airport and once refused to get off a plane at Newark because his ticket read ‘New York.’ In deference to the good mayor, I use La Guardia throughout my website.

It’s hard to tell if this picture was pre- or post-war, but Dad flew DC-3 NC21795, Flagship Massachusetts, from Chicago to New York on March 20, 1942; perhaps it was taken this day, or later that spring (note the trees in the background), by brother Bill, age 10, or maybe my dad. ©Jon Proctor

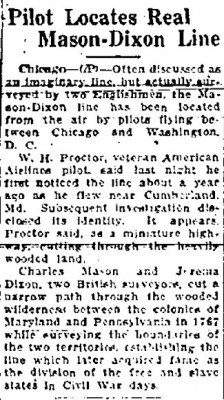

Early 1941 must have featured a rough winter as Dad’s logbooks show numerous cancelled flights, often in Washington and Cincinnati, due to heavy snow; one trip ended with a Chicago diversion to Joliet. But in good weather on June 15, he flew the last American flight into Washington DC’s Hoover Field, nonstop from Chicago, then ferried the airplane across the river to the new Washington National Airport, which officially opened the next day. Although not on the first departure from the new airfield, Dad operated Flight 53, the 5:30 p.m. dinner flight back to Midway Airport.

In 1962, someone with American Airlines interviewed Dad in New York. I have edited the text that was originally transcribed from a recording. Dad was speaking from memory and without prepared notes. The transcript ended rather abruptly, leading me to believe that there may have been more that was not transcribed, and there are obviously some omissions throughout the text that leave us hanging on certain discussions. The original transcriber was obviously not familiar with aviation lingo, as evidenced by some words marked over and/or changed. I altered the text only where obvious corrections were in order, and added a few bits of information for clarity. Some of Dad’s recollections are mentioned elsewhere but I thought it worthwhile to include this interview as it adds some interesting detail to what I’ve written about his career thus far.

Q. How did you get started in this business?

Well, my first line of course was in World War I. I went into the Air Corps – the Signal Corps of the Army was the aviation section at that time. I went in almost by accident but principally to keep out of the trenches and mud. The living conditions would be much better and I just happened to get into the office of a fellow who was accepting pilot training applications in Buffalo on the right morning. He took mine and the next thing I knew I was in ground school. It wasn’t because I wanted to fly although I realized the advantages because I had been living in northern Canada for 3-1/2 years and if we had airplanes up there it would have saved a lot of time. I didn’t know what made them go and it wasn’t romance, for sure.

Q. Well, at least you are honest about it.

A. I am honest as far as the commercial flying goes. After the war we were all pretty sick of flying and didn’t care much about it any more. We were glad to get out of it and we didn’t want to look at another airplane but after a few years went by, why, a few of us began to take any interest again. Meanwhile, they gave me a reserve commission and I found out that I could fly airplanes for nothing and have a little fun. They gave us quarters and let us eat in the mess, and we could fly airplanes at basically no expense, thanks to the government. Occasionally we could use the reserve commission to get two weeks of active duty and learn more flying habits; bad habits as well as good.

Q. During World War I, were you in the States most of the time?

A. Yes, I never left the country; the war didn’t last long enough. I came out of Canada in August of 1917, so by the time I got my flight training [at Ellington Field in Texas] it was spring of 1918 and I was assigned to the first provisional wing up on Long Island, but there were too many trainees in France, so we never got over there.

Q. And following the war?

A. After a few years as a reservist, why they hung a promotion on me and then I happened, for family reasons, to be in Buffalo in the summer of 1927, when General John O’Ryan [http://www.oryansroughnecks.org/jfobio.html] came through there organizing Colonial Western Airways, and at the time I had some Army shifts in Buffalo using check-out reserve officers. The Air Corps sent us up four airplanes and we were flying these fellows around. I got acquainted with General O’Ryan and began to think that maybe commercial aviation did have a future. When he absentmindedly asked me how I would like to fly for Colonial Western I thought it was a real good idea and I started with him. That’s the way I happened to get into it. Commercial aviation was just a challenge and I thought that some day it might amount to something.

Meanwhile, I had a little retail hardware store down in Coconut Grove, Florida, near Miami. I made $50 a month and got into the real estate business in Miami in 1924, I think, and as a matter of fact, I still had an office down there when I started flying for Colonial Western, but I had a partner who kept it open a little while and then closed it. I didn’t have to go back except to wind up some business.

Colonial Western was designated to operate from Boston to Chicago; that was Jim Moran’s idea but National Air Transport (NAT) was operating between Cleveland and Chicago, and at that time they couldn’t get anything over Canada, any kind of a certificate, so we tied our Colonial Western in with NAT, Continental and those lines with Cleveland. And then we started just between Cleveland and Buffalo in December 1927, but we had a certificate at the time. We operated out of Albany with an extension from Albany to Boston whenever we were ready to fly it, so we started between Buffalo and Cleveland on December 17, and the first flight was forced down.

Q. How did that happen?

A. Well, you know how it can snow at Buffalo, and the pilot, who was killed a couple of weeks later, made the first air mail flight to Buffalo from Cleveland. At Buffalo it snowed real hard and hit the airport. The pilot had no radio or anything but he happened to fly right over the airport and saw it under him. There was at least a foot of snow on the ground and it was unbroken; when he came into land, why he couldn’t see where the ground was; there were not tracks in the snow or anything, so he hit the ground pretty hard and went right through the landing gear. The passengers didn’t have to step down when they got out.

Q. There were passengers?

A. Yes, there were passengers. They were about the first flighters. It was an old Fairchild FC-2, licenser number 316.

Q. Were the passengers paying customers?

A. Yes they were. One of them was a printer and there was a story with their names and pictures in the paper; they paid their fare. They were the first and just about the last in that airplane. You couldn’t get anybody to ride in those things. There was no heat in them; no toilet facilities and they were slower than the train. You never knew where you were going to wind up. We put them down in Dunkirk, Erie, any of those places along there, because we found out what the weather bureau never knew and that is that the south shore of Lake Erie is a bad-weather area. The winds coming down from Canada cross the lake and you’ve got a terrific snowstorm.

Q. Did Colonial Western survey that original route?

A. I don’t think it was ever surveyed it. The first time I flew it I had never even landed at Cleveland Airport and I wasn’t sure where it was. I wound up there at night in an old Waco 9 airplane that was not very good. [Click here for more on the Waco and other vintage planes].

Q. What did you do? Fly around until you found it?

A. No, I knew just about where it was. I followed the lakeshore until passing the city, and then flew inland. It was a clear night and the field wasn’t far from the lake. There was an airport beacon, but I had no landing lights. There were lights on around the airport and no one paid any attention to me. I dove on the tower, but if there was anyone there I couldn’t find it out, so I finally peeled off and landed with no runway lights of any kind. I found the hangar and they wanted to know who I was and where I was from. I said, “I have the Buffalo mail.” They replied, “Oh, you have? We didn’t think anybody was coming out.” And I said, “What about your lights, your floodlights?” Well, he called a fellow out at the tower and he said he didn’t know who I was. He heard an airplane flying around but thought it was somebody out for the night air and paid no attention to it so I came in with no lights, no nothing.

Q. Well, this sort of thing … this was sort of routine, I suppose?

A. There wasn’t any routine. You had a schedule and you flew it when you could. We didn’t have any decent weather information, so we just had to find it out for ourselves. We had no communications so we could not radio back and tell them what the weather was. And when we made a forced landing en route, we had to go to the nearest house and get a telephone to call in and tell them where we were.

The same FC-2 used for Colonial Western’s first eastbound mail flight is featured in this publicity shot at Buffalo. That’s Dad in street clothes, helping a boarding passenger. ©Jon Proctor

Q. You had to take the mail sack and get it up to the postmaster?

A. Yes, as best you could. I’ll tell you a funny one. The FC-2 had a peculiar air tube on the engine. It was so designed that in a snow storm it scooped in all the snow as well as a little bit of air, and it would get filled up with snow. We found that out and I was due to go from Cleveland to Buffalo in an FC-2 and there didn’t seem to be any mail. There was a schedule but nobody had posted any letters. Well, they weighed our mail by the sack and I found out that a registered pouch alone weighed about 2-1/2 pounds and we got paid for the trip if we had any mail at all. So I mailed myself a registered letter in Cleveland in order to get some mail.

I started out and ran into snow along the lakeshore, heavy snow. I turned around to go back and that didn’t do any good, so I decided to follow the railroad tracks into Buffalo. But the engine began to slow down and I got to a place where there wasn’t any snow, flew around a little while and the engine would pick up and then I started on and I wouldn’t get very far and that snow was where the engine wouldn’t start up again. So I finally wound up on a farm. I just couldn’t fly anymore, and the snow was about 2 feet deep on the ground. I had this darn pouch and I knew there was nothing in it but my own letter but I had to get the darn thing to the post office. I got a farmer nearby to take me in to town. He wasn’t sure he would get through but he did and took me in, I think, to Erie. That airplane was there a couple of days before we got it out.

Q. Well, if you hadn’t mailed that letter to yourself, would the trip have been canceled?

A. Well, I would have had to fly, probably, because at that time we were short of airplanes, but we wouldn’t have gotten anything for the trip.

Q. Did you have some mail planes too?

Q. Did you have some mail planes too?

A. Well, we started out with these Fairchilds [FC-2s], which we wrecked pretty near as fast as they could put them out, but we only had one fatality and then, I think in January 1928, we got our first Pitcairn D85, they called it. It was a pure mail plane with an open cockpit and no facilities for passengers. So we flew that, and got parachutes because we were going to fly at night and thought that was going to be real dangerous. We wanted to have ’chutes to get out of the plane but I never had to use one.

At about that time I think we were getting, if I remember rightly, about $1.16 a pound for hauling mail from Buffalo to Cleveland; 2-1/2 to 3 pounds was considered a pretty good load, and I didn’t see how we could last beyond spring, but every time they got down, somebody picked it up and they just went on and on.

At first, we didn’t carry passengers at night. However, that didn’t last long. A night flight could be just as good as a day trip, even a little better. We tried to fly passengers at night for a while but there were very few.

This picture from Dad’s scrapbook shows Connecticut Governor John Trumbull and Major General John O’Ryan; it was taken at Newark Airport. ©Jon Proctor

Q. Do you remember what you charged the passengers?

A. No, I don’t, but if you go down to New York, you will find the original schedule showing payment. Earl Rayco of United lives here and he was their past vice-president of sales. He gave us the first consolidated timetable; it was just a little slip of paper. Of course, General O’Ryan was president.

Q. Was he president of all those Colonial lines?

A. That’s right. And he had a very interesting group of directors; he really did. They were a bunch of first-class sports who put up their money and the only thing they ever got out of it was a free ride about once a year. They would go to the airport for a meeting and then go somewhere. Governor [of New York] Trumbull was one that I remember, and he started shooting bows and arrows at these meetings.

General O’Ryan used to have employee parties at his place down in Westchester County. And the directors would come and they would have a pretty good time. When General O’Ryan was president, a fellow by the name of James Walsh was treasurer. He worked himself to death and died of a heart attack sometime around 1929. I don’t recall who the other officers were.

General O’Ryan had an operations officer and I don’t believe his name is in that staff book. He lived in Rome, New York and for some reason didn’t hit off real well with the general. I never knew him real well, but he wasn’t an officer, just operations. We didn’t have a bundle of vice-presidents back then.

Five Colonial Western originals, four wearing parachutes: Ernie Dryer, Merrill Moltrub, Heath Proctor, Ernie Basham and CW Maris. Why three of them were in business suits is a mystery. ©Jon Proctor

Q. Did any of the other pilots stay with American for a long time?

A. Oh yes. Frank Little, as far as I know, is with Eastern, although he may be retired down in Miami. Ray Henries is the only pilot we lost. B. Meyer is in Alaska somewhere; he didn’t stay. Casman didn’t stay. We don’t know where Merrill Moltrub is. Ernie Basham’s father was one of them, and I haven’t any idea of what happened to Weatley. Cy Bittner was there in 1929 and went to Colonial. Charlie Maris and Ernie Dryer stayed. A. Bliss lived in Pittsburgh and the last time I saw him, he was flying for someone, ferrying airplanes.

Q. During your Colonial Western days, what experiences stand out?

A. Of course the operation itself was just a series of experiences. It is hard to tell which one stood out the most because we were always doing very unusual things. At first, we didn’t know that we could fly commercially and at night; we had never done it, you know, on schedule. We didn’t know we could overcome the weather because nobody forecast it back then.

At the time the armed forces had never flown in any bad weather; if it wasn’t clear, they didn’t fly. Nobody ever flew at night. Even during World War II, Pan American didn’t fly at night. They landed somewhere before dark. They would get off early the next morning but we were experimenting so much that every day was an experience.

For instance, we had forced landings. With all single-engine airplanes, we would get into fields so small we couldn’t get out of them. So naturally we would have to tow the airplane down the road to get to a field big enough to take off, but I don’t recall any time that we had to knock one down and set it up somewhere else.

Every time we got a new type of airplane it was a big experience. We had Sikorsky S-38s, two-engine amphibians and flew them between Buffalo and Toronto on a Canadian mail contract, and hauled passengers too. That was a big airplane until we got the Fords [Tri-Motors] up into that part of the country. It was an experience flying with the S-38s. We just didn’t know what we were doing. And then, of course, every first flight over there was a big experience. All the airports around the country were interesting.

We were always getting somebody with advertising of some kind and we always wanted to do something that had never been done before. We didn’t know what a maximum weight load was in those airplanes. If they would take off, they were below maximum weight. I suppose other fellows did the same thing. We had accidents, but only lost the one pilot.

Q. How much did the Sikorsky cost?

A. I think about $60,000.

Q. That was pretty expensive.

A. That was very expensive and we had three of them. We didn’t put them into their natural use very much and let them sit around, which is no economical way to run an airline.

Q. What was the advantage of having an amphibian?

A. We could fly it from harbor to harbor and not from an airport, which was far out in the country. From Buffalo, the marine port that we used was only about 3 minutes from the downtown Hotel Statler, and at Toronto, it was right down in the middle of town too.

Q. Weren’t the passengers ever more leery of those than they were of the others?

A. No, we could get passengers, but the fare was high. We would run more frequent schedules because the depreciation on the airplane was substantial. As it turned out, three airplanes didn’t get enough work, so we had to knock it off. Then we ran that Canadian mail with FC-2s until the Canadians canceled the contract and it just lay dormant until the present operation began, using DC-3s.

Ford Tri-Motor NC9683 now resides in the National Air & Space Museum at Washington, DC. (American Airlines archival photo)

Q. How long were you in Buffalo?

A. Well, we started in 1927. I went down to Newark in 1930 when we got the Fords. I had to go down there to check out on the darn things because we didn’t have any in Buffalo. But we could see that as we progressed far enough that mail planes were not going to be there anymore. For a while, I wound up in a different capacity. I think they called me “chief pilot.” I went through divisional superintendent, then back to flying.

A lot of people took a crack at it, but it wasn’t a very pleasant job. I think anybody who was with the company in the ’30s can tell you about the hodge-podge of small airlines being knit together. Everybody who was head of one of those small lines wanted to have the whole thing. Also, there was a surplus of personnel and they were struggling too. So at that time you were more interested in watching over your job and trying to keep it than you were about doing the job itself. That didn’t appeal to me, so I went back to flying.

Q. How long was O’Ryan around?

A. He was there until he sold out to Aviation Corporation (AVCO) I think around 1929 or 1930.

Q. And did he become president of AVCO?

A. I think he was a director for a while.

Q. Juan Trippe was somehow involved.

A. He was one of the regional directors. I don’t think he was an active employee, not to my knowledge.

Q. I don’t think he would like to be reminded of that.

A. Oh, I don’t think he would object. I had him on board flights, you know, and he seemed right at home.

Q. What was O’Ryan’s background?

A. He was a National Guard officer, a major general who commanded the National Guard division, infantry division, which was either the 26th or 27th, and broke the so-called Hindenburg line, its principal claim to fame against the Germans; they came back in a blaze of glory. There was a big parade in New York City and then the general not only commanded the New York National Guard, but he had some kind of an official capacity with the governor’s office, and he was eventually retired by the state, before he died.

[Click here for a story about General O’Ryan’s accomplishments during World War I.]

He was a lawyer and connected with a prominent firm in New York whose name I can’t recall. And General O’Ryan was years ahead of his time as far as aviation was concerned. He was very frank to say that we didn’t know anything and his approach to selling the stock was wonderful because he somehow or other would get a luncheon set up where he was the principal speaker and would sell stock.

His approach was: We are going to start an airline. We believe that air transportation has a place in the future; we don’t know how to go about it but we are going to try and we need some money. If anybody is sport enough to buy some of our stock, we would be glad to take his money. We are sure we won’t make anything during the first five years. After that, why the future will have to take care of itself. We will just have to play it be ear; we don’t know.

And you would be surprised how often he got them to buy stock.

Q. Well now, all those various companies were separately incorporated, weren’t they?

A. Yes.

Q. Well, was that to get more money each time and start it all over again?

A. No, because they sold stock in each company. Mostly there were people who were interested in the territory and I think that was the only reason. Of course they had separate mail contracts and they were all numbered. Colonial mail between New York and Boston was, I believe, the first contract although I don’t think they were the first operator. I think NAT maybe started in 1926, but not long before Colonial, maybe a few months. Then they formed Colonial Western and then Canadian Colonial, which had to be two separate corporations and I surveyed the Canadian Colonial routes. I went up to Montreal for them.

The general tried to get me to survey the line down to Binghamton direct. I flew it a few times but that country had such a horrible terrain and weather; I didn’t think it was a practical route, although some other guys started it without any trouble. Otherwise we still had to go around by following the New York Central [railroad tracks] by way of Albany.

Q. How were you paid?

A. A trip that was started got paid. I was working for a flat salary then, for a while. Later we got paid on a mileage basis. I think it was 2 cents a mile. If you were out an hour, you figured the airplane was good for 100 miles per hour, so you had flown 100 miles and earned two dollars.

Q. Well, how many hours a month would you be flying then?

A. Not very much because it was only 195 miles from Buffalo to Cleveland. The flying time was about the same as an express train. So we didn’t fly too many hours.

I know one time I broke a record. What happened was that the tachometer on the airplane went haywire in Cleveland and we didn’t have much in the way of spare instruments, so I couldn’t tell the speed of the airplane. At that time, we could operate any airplane that would fly; we weren’t bothered with a lot of regulations. So I took the airplane from Cleveland to Buffalo and when I got there, I was astonished to find out that I made about the fastest trip that had ever been flown over that route. I did have a big tailwind and I think it was about an hour and twenty minutes. The scheduled time was about two hours, maybe two and one-half.

We usually would go one way one day, then back the next. We were only flying about two hours a day, so 60 to 70 hours was probably about a months’ work. And then that went from the sublime to the ridiculous. The pay for a month was $100 to $120 and then they began to realize they had to put a maximum on it.

Q. Now, when was the period during which you got up to $100, $110 and $120?

A. Well, I was down in Cincinnati and that was around 1931, 1932 and 1933. And we were flying the Pilgrims and Fords then. You see, we didn’t get paid for a vacation so what we would do is this: One fellow would go on vacation; that’s what ran us up. None of us were scheduled for that kind of money, only $80, $90, $100. But they clamped down on us and was 85 maximum per month. That was when the regulation went into effect, but right away we didn’t qualify because we weren’t a legal flight.

Q. When did you go to Cincinnati?

A. I went to Cincinnati in May 1932. I stayed there until 1935, then went to Chicago and stayed there from then on.

They sent me to Cincinnati as what they called a division manager, or division superintendent, I guess. At the time, they had things all chopped up into small divisions. In Cincinnati they were responsible for all the operations that happened between Cincinnati and Indianapolis, Cincinnati–Columbus and Cincinnati–Louisville. I don’t think I put up with that too long because it wasn’t very pleasant, so I got back to flying about 1933.

Q. Do you happen to know when Colonial sold out to AVCO?

A. It really must have been in 1930.

Q. Yes, but did AVCO pay more than Colonial was worth?

A. No, I don’t think so. I haven’t any idea what they did; I think there was an exchange of sock; in fact I know they did that. I am not sure that there was any money involved.

AVCO picked up the Colonial stock and exchanged it for AVCO. And at the time, they gave quite a few of us a bonus in stock, which was maybe $2 a share. And I think that was in 1929 or 1930, but you see, if I recall, AVCO had 72 different corporations. And somebody told them to divest themselves of the holdings. For instance, Fairchild Camera and Fairchild Factory. Fairchild Camera split off and is very good now. You probably have a list of the operating companies. I think there are about fourteen.

Q. Did Colonial or Colonial Western operate any flying schools?

A. They operated them in Buffalo but not for any length of time because they got them started just before the boom bust [stock market crash] and also the flying schools – we called them the Colonial Flying Service. That was an incorporated company; we sold airplanes and ran the schools in Buffalo. The ground school was connected with the universities in Buffalo.

We financed the thing and ran the ground school operation. One of the fellows from over east later became governor of Maine. They were the officers in the company and they started the school by arrangement with local people at Rochester and Syracuse. If there were any other places, I don’t know of them. But we didn’t run them very long because the bottom just fell out of things; nobody had any money and it was the same thing with the sales department, trying to sell airplanes.

Q. Outside of the early planes you flew commercially, what characteristics do you remember most, either in a loving or unloving way?

A. Well, I’m not sure if I remember any of them unlovingly. The FC-2, in some respects, was a very nice airplane but it didn’t go anywhere. It was slow and you couldn’t see ahead of you. The engine was right out in front, but it was a very stable airplane.

And then the mail planes. The Pitcairn was a ground-loving fool but at that time it was new and flew a little faster, not much; 90 to 100 miles per hour, and maybe a fast one would be good for 105. We had little Stearmans and I don’t know what else. And then the next Fairchild we got was a struggle buggy.

Q. How so?

A. Well, it was a single-engine airplane, it couldn’t haul very much of a load. It couldn’t carry any ice that amounted to anything. We lost an airplane between St. Louis and Chicago with ice. The thing just couldn’t fly with it.

The Lycoming-powered Stinson Model U tri-motors entered service with American in September 1932. (American Airlines archival photo)

Then we had all kinds of Stinsons. I never loved those things. They had three engines and they would do real well on two, but they were slow and didn’t carry much of a load. I guess the maintenance on them was very expensive. No one cared very much about them. We had a single-engine Stinson too, then two types of tri-motored Stinsons. You know, we got those principally when we bought that outfit to operate between Cleveland and Chicago.

And I guess we went from that to Fords and from Fords we had some Condors. That airplane couldn’t carry any ice at all. It was a big airplane with crossed wires and those things would quickly load up with ice. And as far as I know, it was our first experience with carburetor ice. One of our airplanes landed in Ohio with both engines stopped and we couldn’t figure out what in the world had stopped them both, but I knew later that it was carburetor ice; it was the first time we had ever seen it.

Q. How did you people feel about introducing the Condor sleeper service? Did it seem like a bunch of “…”?

A. Well, of course we were in it to see how it would work out. A lot of people started buying tickets and we saw it was useful. You know May Bombeck, don’t you? May was on a Condor when it burned up. We thought it was a pretty good airplane but again it had an awful lot of wings. In every airplane, the engine was different for some reason.

Q. During the period in which they were trying to integrate various firms, you said there were dozens of different firms scattered all over. Did pilots check out with each new plane?

A. Well, we checked out but of course single mail planes were about the only ones you could go out and practice in and say okay, I’m ready to go; there was nobody to tell you. I think the first planes that we actually checked people out in were Fords. Up until that time you just got in and flew and found out what the speed was and made some landings. Whatever you could get in the way of manuals wasn’t much. You tried to familiarize yourself with the airplane so I would just sit in the cockpit.

Even in World War II, the way we familiarized ourselves as airline pilots was to read tech orders, which were the equivalent of operations manuals. We would read those things and then we would get into the cockpit and sit and look for some way to fly, no matter where things were. For instance, an A20 was a single-engine, single seater. All we could do was to take it off and fly it, take it up and stall it, to see what the stall speed was, and then come down.

By the time we got Fords CAA inspectors began to go along with us. We had to get our rating from them; we couldn’t get it from our own people.

Q. When did you get your license?

A. In 1927. They sent some fellows around the country to issue licenses; there were some flight tests and so forth. As a matter of fact, all our applications went in about the same time, but the ones on top of the stack came out with lower numbers. Mine was 791. Jack Little’s application was in there and his number is 50 or 51. But 1927 was the year they started issuing licenses.

Q. As far as the company was concerned, was the first formal training towards the instrument school?

A. I don’t believe there was an automatic ground school; it was just a flight instrument course and that was for an instrument rating. Nobody had them; we had been flying on instruments to some extent but there wasn’t any such thing as an instrument rating. So it was the CAA inspectors who came around to take us on test flights. Then Colonel Day came around. I was at Cincinnati when he gave everybody some instructions on instrumentation until an inspector could check us out. I wouldn’t call it organized.

Q. Well, when was the first organized training?

A. The first I saw was on the DC-2s, when we had some flight instruction, but I never got any. And I think it was after the war that we first started our organized training, including the ground school on the airplane, ground flight instruction and the rating on that particular airplane.

Q. Well, you were back flying again. At the time the DC-3 came along, you were in Chicago?

A. Yes, not long after I moved from Cincinnati; before that we were flying DC-2s.

Q. Do you remember any inaugural flights?

A. Well, I flew the first nonstop flight from Chicago to Washington. I remember that one if you can call it an inaugural. It wasn’t inaugural as to the equipment, it was the first nonstop. Then I flew a first flight back in 1928 from Buffalo to Albany eastbound. But that nonstop from Chicago is the only one I can recall.

Q. That wasn’t the one with a food problem?

A. We got the food but no trays. I was getting impatient. Did I tell you about pulling the steps out from under?

I think they had the food, but there were no trays. Neal Dyke was standing in the doorway, and I said, “Come on, let’s get out of here, I’m tired of waiting for the trays.” I agreed, and then C.R. grabbed the boarding ramp and pulled it away. Poor Neal had one foot on the ramp and one in the airplane and nearly fell; I thought that was about the funniest thing.

Returning from Washington I had the press aboard and between Pittsburgh and Indianapolis, the icing conditions were low down and I wanted to get above it and the rough air. I was looking to get up about seven or eight thousand feet and I couldn’t get ATC to track me until I told them my passengers were getting sick. They wanted to give me about five thousand feet, and I’d get in that and my air speed would freeze up. And then I asked for seven or eight thousand feet and they wouldn’t give it to me.

Meanwhile, the newspaper reporters were getting sick back there, so I finally told ATC my passengers were getting sick; you’d better do something. So then they let me up, but I had a miserable ride. Ralph Damon was president. I don’t think he believed me when I told him about it.

Q. In real rough weather like the when passengers got sick, did the crews get sick too?

A. Oh I never heard of a pilot actually getting sick. I could get sick in the cabin but never in the cockpit.

Q. Why is that?

A. Oh, I think you are pretty busy and it has something to do with your eyesight; your vision and color has something to do with it. For instance, the Condor had tan upholstery and we had more airsickness in that plane than in any plane I ever flew. I am not sure that there wasn’t some tan in some other planes but in the cockpit the vision is around and you can look at everything. Also you are thinking of something else. I never got sick I the cockpit yet I could get sick in the cabin.

Q. Did you ever have any other experiences of that sort when you had a bunch of newspaper or so-called important people aboard?

A. I tell you, my flying life as I look on it was not ordinarily a series of unusual adventures. Emergencies, I suppose I had my share of but we overcame them all. I think the worst thing that I ever did was blow a couple of tires over at Washington Airport. I had my share of emergencies in the early days, forced landings in strange fields and of course we were sticking our noses in places where we had no business, but after you’ve been there a couple of times, well, you know….

Winds of War

Dad was in Washington DC on December 7, 1941, when Pearl Harbor was attacked, plunging America into World War II. I remember my mother telling me after his death that beyond the shock of the event, Dad was somewhat relieved. Ever the pragmatist, he felt the sooner we got in and achieved the ultimate victory, the sooner he would be back home with his family, including two young sons and wife Lucena, who by then was five-months pregnant with me.

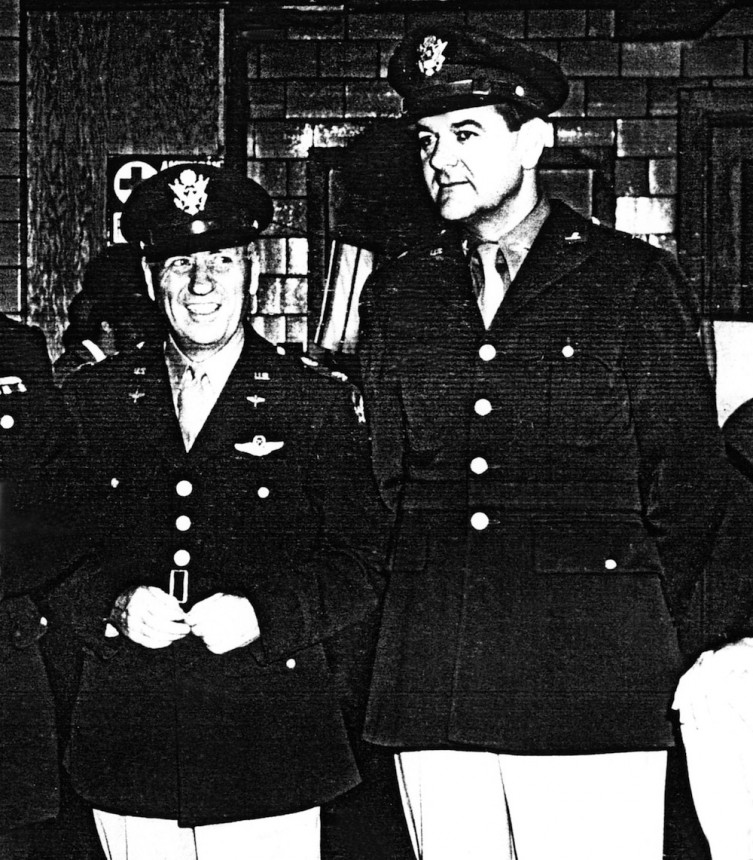

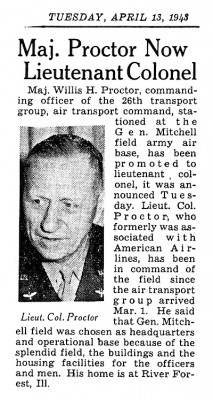

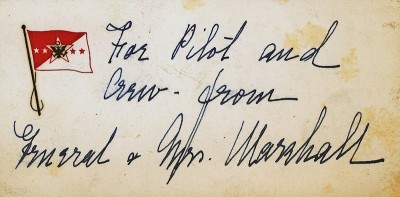

On March 1, 1943 Dad became commander of the 26th Transport Group, Air Transport Command (ATC) at Michell Field in Milwaukee and was promoted to Lt Colonel. Four months later he was named ATC group commander at New York’s La Guardia Airport. A September 15–17 assignment saw him flying Army Chief of Staff George C Marshall and his wife to Mexico in a C-47, where they represented President Roosevelt at the Mexican Independence celebration.

None of Dad’s assignments seemed to last very long. He was sent overseas on January 30, 1944 as Air Inspector of the ATC India-China Wing in the CBI (China-Burma-India) theater, flying the famous “Hump” across the Himalayas in C-47s or, if he was lucky, in a C-46. Following a promotion to Commanding Officer of the CBI India wing, Dad became a full Colonel.

Like most WWII vets, he spoke very little about the war. In retrospect, I think he would have answered questions and I should have interviewed him at some point. I do recall asking if he had ever had an engine quit on his way over the Hump and he replied, “I wouldn’t be here today. There were occasions when one would run rough, but you had to make the best of it and keep on going. There were no alternate landing spots in those mountains.” Dad also once commented that you did not want to be on the losing end of “that war,” referring to the atrocities committed during and after it. For a comprehensive LIFE Magazine story on the Hump, click here.

Dad left India for the last time on June 1, 1945. Flight records indicate he flew as first pilot on a 4-hour C-47 segment to Casablanca. Two days later, he was the command pilot during a three-stop C-54 trip. The Atlantic crossing began at Casablanca, a 10-hour, 55-minute segment to an unidentified stopover, then a 5-hour, 55-minute leg to Stephenville, Newfoundland and finally on to La Guardia Airport in New York in 7 hours, 40 minutes, arriving June 4.

Dad and an unidentified pilot at the Yunnanyi Air Base, China in 1944. © Jon Proctor. More information on this critical landing field can be found at http://tinyadventurestours.com/Eng/Topics/theHump.html

After recovering from dysentery for a month in a Coral Gables, Florida hospital, Dad was relieved from active duty and returned to his family in Chicago. His decorations included the Air Medal, Bronze Star Medal, American Theater Campaign Ribbon and Asiatic Pacific Theater Campaign Ribbon w/2 bronze stars.

While going through his military records I found a 1947 letter addressed to Dad from Adjutant General Edward Witsell in Washington DC, stating that he had been recommended for appointment to the rank of brigadier general in the military reserves. My brother Bill told me Dad had discussed the offer with CR Smith and decided against it. Although still in the military reserves, he realized it would require more active duty time and make little difference in his military retirement benefits.

Dad with CR Smith, probably postwar or close to it; both remained in the reserves so it could have been during later active duty; wish I knew more about this picture. ©Jon Proctor

Back with American

With the war behind him, Dad began completing route checks with American Airlines on August 27, 1945 and went back to his Chicago-to-Washington DC and New York DC-3s flights. By then he had 12,500 hours in his logbooks, including nearly 800 during the war.

Brother Bill took this picture of an American DC-4 taxiing at Chicago-Midway. On the back of the print, he wrote, “Dad flying.” ©Jon Proctor

American began taking delivery of a large DC-4 fleet the following February, all refurbished military C-54s, which Dad was already qualified on, although he still completed ground school and flight training again. Beginning in mid April he began regular DC-4 flights, for the first time operating turnarounds to Washington and occasionally New York. This meant being home every night thanks to the faster four-engine Flagships. Eastbound flights to Washington averaged just under 3 hours, and a bit longer against the winds coming back. Fourteen monthly roundtrips became the norm. I don’t have any timetables from that period, but Dad’s logbooks show Flights 62 to Washington and 61 returning, then later Flights 60 and 67, schedules he flew for many months.

DC-6s, American’s first postwar-built airliners, entered service in May 1947. After training at Ardmore, Oklahoma, Dad operated his first trip on May 14, from Chicago to New York and back the same evening.

The new Sixes were pressurized and faster but possessed an Achilles Heel that later resulted in the type being grounded. Dad’s logbook indicates “rear baggage compartment fire” on a May 25 Chicago-Washington DC flight although it apparently was not serious as the same airplane was flown back to Chicago the same day on a regular flight.

DC-6 NC90712, Flagship Texas, the airplane Dad set the speed record with, as seen in this American Airlines photo.

Operating a DC-6 as Flight 62 on June 15 with a full load of 52 passengers and again from Chicago to Washington DC, Dad set a speed record of 1 hour, 42 minutes and 25 seconds, clipping nearly 8 minutes off the previous record. A newspaper clipping stated that the average speed was 355 miles per hour. The scheduled time was 2-1/2 hours. Gordon Purdy was the first officer, but the flight engineer position had not yet been established on DC-6s.

In October 1947, a United DC-6 crashed at Bryce Canyon, Utah after its crew reported an on-board fire. A few weeks later an American Airlines DC-6 suffered the same problem but was safely landed at Gallup, New Mexico, and the airlines voluntarily took the type out of service. After inspection of the American airplane it was discovered that fuel from a wing tank overflow safety valve was sucked into the cabin air-conditioning system. Resulting fumes ignited the cabin heater, causing an uncontrollable fire.

Dad went back to the DC-4, which took over for the grounded Sixes until they returned to service in March 1948. He seemed content with New York turnarounds until that fall and then flew trips to Phoenix, Tucson and Los Angeles, perhaps scouting out retirement locations.

Still active in ALPA, Heath was occasionally off his flying schedule for union meetings and conventions. He also continued in the military reserves, which required annual active duty status although by then he was attached to a group at nearby O’Hare Field.

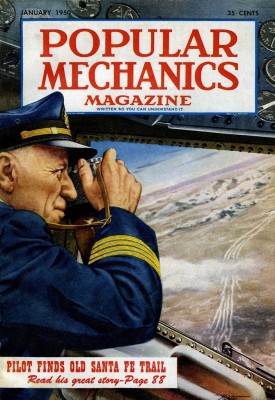

It was during one of his Chicago–Tucson trips that Dad made a startling discovery. Gazing out the cockpit window just west of the Cimarron River over Kansas, he noticed ruts on the ground exposed by wisps of snow blowing across the prairie. It was no haphazard pattern but a trail, wide in places and occasionally narrowing headed majestically toward the southwest. An avid American history buff, Dad knew at once that he had found the historic Santa Fe Trail.

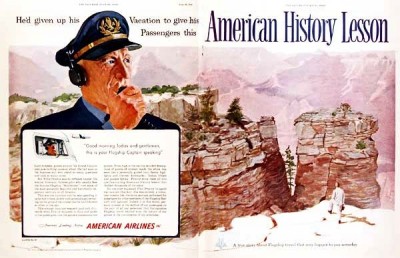

When the editor of Popular Mechanics magazine got word of the discovery, he invited Dad to join in on an exploratory trip along the trail. The adventure became a feature story in the January 1950 issue, with a painting of Dad on the cover. This was the first time the image of a person was given such an honor. Click here to read the feature story.

Time to Retire

It was not until 1960 that the government instituted the age-60 airline pilot retirement legislation, called by some “Elwood’s Edict,” after Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada, head of the FAA, who was instrumental in establishing the regulation. But most airlines already had the policy in place, including American Airlines.

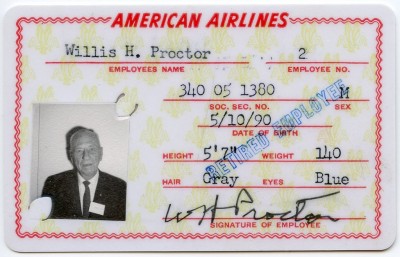

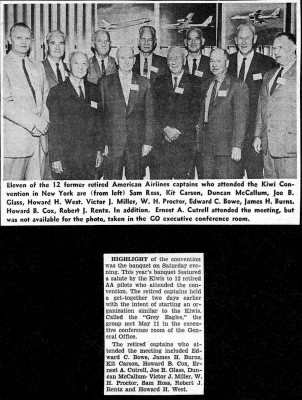

Heath Proctor reached that milestone on May 9, 1950, the first active airline pilot in the United States to do so. His pilot seniority number had been number 2 until Ernie Sloniger left the company in June 1946; Dad then became number 1 until retirement.

Perhaps wanting to stretch his career to the max, he flew his final trip on the last day of the month, a New York turnaround that wound up diverting to Newark account weather. Upon returning to Chicago’s Midway Airport at dusk, he was greeted by many of his fellow pilots and escorted back to American’s operations office at the hangar, for an impromptu celebration and toast.

Still in perfect physical condition (he didn’t even need reading glasses), Proc signed the crew flight time record book in Operations, turned in his manuals and called it a career with 24,000 landings and 16,121 hours in his logbooks.

Of course Dad wasn’t happy about leaving the cockpit. “I don’t want to quit flying,” he said. “No flyer ever will. But like a bad habit, the best thing to do is chop it off and forget it.”

A toast from his fellow pilots. ©Jon Proctor

A toast from his fellow pilots. ©Jon Proctor

Being first had its downside, including a meager retirement package, which was even less than his military pension. As a result, he remained with American for an additional seven years, serving as the head of pilot training at Chicago.

During that time, brothers Bob and Bill were both out of the house. Mom, Dad and I took a few family vacations and he and I took a couple of father-and-son trips.

He still held cockpit jumpseat privileges and occasionally had to sit there in order for all three of us to get on a flight. But I recall several occasions when he actually moved off the jumpseat and flew the airplane as well, back when rules were more easily bent. Once I was invited up to the cockpit on a DC-6 between Detroit and Chicago, with Dad occupying the captain’s seat, and got to remain up front for landing at Midway Airport. Another time we were flying from Chicago to Washington on a DC-7, my first ride in one, and again Dad got some ‘stick time,’ although he came back to sit with me before landing. I’m sure it was easier for him to talk about ‘forgetting it’ than it was to actually quit flying; fortunately there were a few opportunities to get back in the left seat.

To California

Dad was featured in this June 1953 ad that ran in The Saturday Evening Post and other publications, well after he retired from flying.

Dad finally took full retirement in August 1957 and was given his 30-year pin. In those days, only a handful of employees could claim membership in American’s 3-Diamond Society, named for the gem-studded pin handed out to those who had given three decades of service to the company. His payroll number was 02; Goodrich Murphy – who designed the famous American Eagle emblem, was assigned 01.

That same month our family moved to La Jolla, California, then a quiet enclave on the north end of San Diego. Several years earlier Mom and Dad had begun seriously looking at locations from Santa Barbara south. A major consideration was access to nearby military installations that provided medical care, post exchanges (PXs) and inexpensive gasoline. Another requirement was close proximity to an airport served by American Airlines so they could utilize their travel privileges. In those days, there was little or no reciprocity between carriers so locale became even more important.

Dad dabbled in real estate but did not fly an airplane again, instead playing an occasional round of golf and enjoying the slower pace of retirement. But he and a few other retired pilots gathered to form The Grey Eagles, an organization of American alumni pilots, and served as the group’s first president. Always happy to be back among his former colleagues, Heath looked forward to annual pilot reunions, and seemed content to be an onlooker as the Jet Age swept across the world in the late 1950s.

After returning from his first jet flight (aboard a Boeing 707 en route from Los Angeles to New York) in 1959, I recall asking him what the new jets were like. He responded with one word: “Fast.” Fast indeed, especially when compared with the airplanes he had first flown some 40 years earlier. Another time, arriving on a 720 from Los Angeles, he was invited to sit in the cockpit and laughingly commented, “They wanted to give me the landing.” Serious or not, Dad chose to decline.

Unfortunately I barely got a glimpse of American history through the eyes my father, who was born 10 years before the turn of the century. He did mention the assassination of President McKinley in Buffalo when Dad was a child, and recalled his schoolteacher exclaiming that January 1, 1900 was “the first day of a new century.” Apparently school kids didn’t get New Years off in those days, or perhaps it all took place a day later.

When American Airlines brought its restored Ford Tri-Motor to San Diego in 1963, Mom and Dad were invited to a reception at Lindbergh Field. He once flew this Ford, NC9683. It now resides in the National Air & Space Museum at Washington, DC.

Once, while I was watching the ‘Annie Oakley’ television program, Dad commented, “She shot with a rifle, not a pistol, and she wasn’t that pretty,” referring to actress Gail Davis on TV. When I asked how he knew, he told me how, as a young boy, he saw her perform with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveling show, shooting clay pigeons from a standing position on the back of a trotting horse; I was amazed!

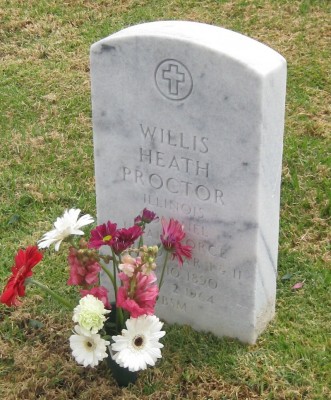

Captain Proctor – or should I say Colonel Proctor – passed away at the San Diego Navy Hospital on November 2, 1964; he was 74.

Captain Proctor – or should I say Colonel Proctor – passed away at the San Diego Navy Hospital on November 2, 1964; he was 74.

I was 22 at the time, and now wish I had been able to tap deeper into his vast lifetime of memories. There were no video cameras or even affordable audio recording devices to capture his life experiences. Having been born when Dad was nearly 52, I didn’t get much time with him on an adult basis. Perhaps I would have had more questions and a greater appreciation for all he witnessed, especially the dramatic growth in aviation.

But never mind. I’ve still got those memories of our time together and what a truly great dad he was. I will always treasure them.

Epilogue

On the 50th anniversary of Dad’s retirement, I wrote a tribute to him in my Airliners Magazine Up Front Column. Click here to read it.

After my brother Bob passed away in 2010, I found among his possessions what appears to have been the beginning an autobiography that Dad never finished. I had never before seen nor heard about such an effort, and wish there were more chapters. Here is what I found:

Chapter I

THE CHALLENGE

© W. Heath Proctor

In the summer of nineteen hundred and twenty-seven there was a challenge in the air. Men’s thoughts were turning to commercial air transportation and a burning desire was generating in the breasts of sons of pioneers. A desire to be a physical part in the development of a new form of transportation, a new communications route through the skies, civilization’s last frontier.

I had lived three years in the sub-arctic when we received mail only three times annually and supplies but once, and where men traveled on foot, in canoes and ran behind dog sleds when they wanted to go anywhere. Dreams leapt the centuries that would be required to bring those remote places closer by surfaced roads and railroads, and envisioned airplanes cutting travel time from months to days. Airplanes that would supply remote places with dry and undamaged supplies, carry the valuable furs of the North to market in a week instead of eighteen months, move prospectors and trappers about the country so they could make more profitable use of the short seasons and save lives by taking the sick and injured to the doctor, or a doctor to them.

At a businessmen’s luncheon the principal speaker proposed, “Gentlemen, the United States Post Office Department is operating an experimental Air Mail route across the country in an effort to determine the potentialities of air mail service. Recently they reached the decision that the project is practicable and should be more fully developed. They feel that the transportation of commerce for hire is a proper job for civilian agencies rather than for the government, and have decided to award contracts to reliable groups of civilians for the movement of United States Mail over certain specified routes.

I head one such group and we have been awarded a contract. Frankly, although we have had limited experience, there is much about air transportation that we don’t know. We don’t know what our operating costs are going to amount to or where our personnel will come from. We don’t know what measure of public acceptance we will enjoy, whether they will ride as passengers and entrust us with their letters. Financial profits are, for the present, highly questionable. We feel sure there will be no dividends for at least five years and probably longer. Now, if there are among you gentlemen those who would like to go along with us on a sporting proposition designed to test and develop something new that may become one of the great boons to our civilization, and who are capable of bearing the disappointment of failure should we honestly fail to gain financial success, we will welcome your participation and promise you an honest and intelligent run for your money.”

I was a sunk duck. I had no money to invest but within a week I was hired as an Air Mail pilot.

Ours were not the earliest visions of air transportation. Our first flight passengers received as souvenirs a small bronze plaque commemorating the flight and bearing in raised letters the words, “Costly Bales Through Purple Skies,” a quote from a far earlier visionary. Our dreams were a bit more practical and, as the days and months passed, they sometimes became nightmares. Had we known what lay ahead we wouldn’t have been so cocky. As a matter of fact, many of us might have preferred a warm office from which we could grin at those dopes who were crazy enough to bore holes in clouds, summer and winter, instead of staying on the ground where they belonged.

Some decided that the business was not for them and quit. Some died, but the rest stuck with the flying machine. In many a bull session around a coal stove or poker table we called each other fools with no one denying the epithet. Those who stuck and lived have never been described as regretful. They didn’t get rich, but they lived those days and years when airplanes grew larger, faster and stronger, while weather lost much of its mystery and until finally Mr. and Mrs. John Q. Public cast aside their fears and, with children along, became willing to stand in line for seats of flying machines because those seats offered them the product of our dreams: a safe, fast and beautiful ride over our highways in the skies, our highways by right of conquest.

Nineteen twenty-seven found little sense of inefficiency in the hearts of air mail pilots. The performance of the airplanes was erratic and sometimes unpredictable but we had flown them, and were flying them, as they came. The surplus military planes from World War I were about washed out, and new machines boasting such improvements in design as high-lift wings, and in structure as tubular metal framework, were appearing on the market and riding the boom of popular spending. Many were just new crates around an old 90-horsepower Curtiss OX-5 engine, but the radial engine of some 220 horsepower was appearing where there was money to buy. Air speeds ranged from 80 to 110 miles per hour. Gross loads were what you could cram into the bins and get off the ground with. Structural strength was something to wonder about and hope for, but there was never a lack of will to try in the cockpit. We didn’t like the looks or performance of some of those planes, but we figured that if the Great White Father and the Constitutional Congress felt that the North American people needed an Air Mail service in their march to a better and faster life, we were willing to furnish the fresh meat necessary to operate the aircraft.

Chapter II

AN INAUSPICIOUS BEGINNING

© W. Heath Proctor

I’ve never been connected with, nor personally know of, any first flight, or particularly ceremonious flight that operated according to plan. I learned to shy away from special events like a horse shies from a rattler. Something always happens that isn’t on the agenda. The weather goes wild, there is a mechanical interruption or delay, someone forgets the food or the distinguished guests get sick. I learned this in the early years but could never do anything about it.